June 2018 was marked by the amplification of distant warning sounds regarding the fate of abortion rights in the United States. Although within recent months there have been positive steps forward, such as in Ireland and Argentina, within a broader politics of abortion, the medical procedure remains illegal and inaccessible across large swaths of the globe. Since abortion was legalized in the U.S. in 1973, anti-abortion advocates have chipped away at the constitutional “right” such that its current status is more of a “privilege.” After a recent victory for “crisis pregnancy centers” (fake clinics), in combination with the resignation of Justice Anthony Kennedy from the Supreme Court, the past few weeks have sounded further alarms within the decades-long “abortion wars.” These wars have included not only devastating anti-abortion legislation such as the Hyde amendment, but violence against abortion clinics (including 11 murders and 26 attempted murders) and the quieter yet just as nefarious technologization and romanticization of the fetal heartbeat.

***

The “Heartbeat Protection Act” of 2017 (H.R. 490) would make it illegal for physicians to “knowingly perform an abortion: (1) without determining whether the fetus has a detectable heartbeat, (2) without informing the mother of the results, or (3) after determining that a fetus has a detectable heartbeat.” Introduced by the 115th United States Congress, the bill is a nation-wide version of existing, state-level “heartbeat bills” promising to “protect every child whose heartbeat can be heard.” The “Heartbeat Protection Act” would effectively make it illegal for doctors to terminate pregnancies after six or seven weeks’ gestation, at which time a heartbeat typically can be detected. The bill makes it clear that the abortionist, and not the pregnant person, is the moral agent within the context of pregnancy termination: “A physician who performs a prohibited abortion is subject to criminal penalties—a fine, up to five years in prison, or both,” while “A woman [sic] who undergoes a prohibited abortion may not be prosecuted for violating or conspiring to violate the provisions of this bill.” As of May 2018, a total of 59 heartbeat bans have been proposed over the past seven years.

“Heartbeat” bills not only articulate the subjecthood of physicians and the objecthood of pregnant bodies; they also rely on the animating capacity of sound in their efforts to enliven embryos and fetuses. In Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect, Mel Chen describes “animacy” as a “slippery” value problematizing the contemporary biopolitical boundaries between ontological categories dividing “the living” from “the dead” (9). Hierarchies of animacy indicate the ways in which entities perceived to be nonhuman or nonliving, such as monkeys, lead, and toxins, are endowed with racialized and/or gendered “human” qualities through the politicization of language and figuration (The 2007 “lead panic” in the U.S., in which Chinese-manufactured toys were viewed as unidirectional transmitters of racialized toxicity, is an example). The sounds of fetal heartbeats are implicated in the construction of a hierarchy of animacy as they render pregnant bodies less animate. Drawing from Chen in exploring a politics of animacy can help us understand the animating and silencing capacities of reproductive healthcare legislation and restrictions. Within this politics, the fetal heartbeat becomes so loud that it silences the pregnant person.

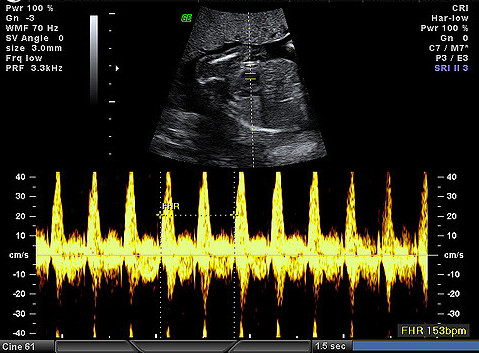

A sonogram and Doppler visualization, Image by Flickr User DYT, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This silencing and objectification of pregnant bodies occurs not only through anti-abortion legislation but in the sphere of the everyday. The pregnant body becomes animated with the capacity (and expectation) for nurturing and selflessness, while its contents are animated with qualities of potentiality and personhood. As feminist phenomenologist Iris Marion Young points out in an essay on pregnant embodiment (which can be found in her collection On Female Body Experience), the pregnant body not only becomes a synecdochal figuration for heteropatriarchal structures and narratives, but is experienced as “Other” even from a first-person perspective: “in pregnancy I literally do not have a firm sense of where my body ends and the world begins” (50). Pregnant people can expect to be stared at, to get asked personal or even inappropriate questions, and to have their bodies touched without consent as they move through public space. The presumed ownership over female-presenting bodies is magnified when these bodies are perceived as housing another living being presumed to be the progeny and property of a male “father figure.” The blurred line between internality and externality allows for a further window through which the surveillant male gaze can stare, and through which the sounds of sonic patriarchy can be broadcast.

Image by Flickr User jennykarinaflores, (CC BY 2.0)

The concept of the “male gaze” is at this point well recognized; “sonic patriarchy” can be heard to be its aural counterpart. Sonic patriarchy is a concept I have theorized in order to give name to the domination of a sound world in gendered ways, as well as to the control of gendered bodies via sound. In public space, sonic patriarchy can be heard in the catcalls and whistles and mansplaining that grope their way into the aural space of female and feminine bodies. And, as Christine Ehrick points out, masculine voices can be heard as a signifier of power within a “gendered soundscape.” Sonic patriarchy can be heard within private space, too; recently, a friend texted me about a roommate’s boyfriend who never bothers to use headphones when listening to music in the living room “even though he doesn’t even live here!” Both the male gaze and sonic patriarchy are misogynist and objectifying forces that shape and control space, demarcating boundaries of safety, mobility, and accessibility for many female and gender-nonconforming bodies. However, these modes of surveillance and control have been discussed primarily through a visual lens within the realm of feminist and queer theory.

The sonification of the male gaze manifests in mundanities, such as the daily catcalls women are subjected to in literally every corner of the world, and in more disturbing contexts such as anti-abortion rhetoric, which I’ve observed through my ethnographic work at abortion clinics throughout the United States. At these demonstrations, the bodies of clinic patients are invaded both literally, with the shouting of the protesters, and figuratively, in the making-public of the figure of the fetus with four-foot-tall posters depicting mangled fetal body parts. Ironically, these inanimate posters animate the figure of the fetus as they lend more humanity and visibility to the imagined contents of a pregnant body; meanwhile the pregnant person fades into a mere backdrop for this spectacle. This voyeurism also occurs sonically, as the protesters ‘give voice to’ imaginary fetuses by yelling “Mommy, mommy don’t kill me!” In the space of the clinic protest, feminized ears exist as gendered and sexualized organs in which masculine vocalizations can penetrate and reverberate. Just as misogynist conceptions of female sexual receptivity frequently ignore the word “no” and the concept of consent itself, these vocalizations ignore the active non-consent of the patients as they persistently rupture their aural space.

The patriarchal control of the sound world, whether on the sidewalk outside an abortion clinic or in a doctor’s office, is a reminder of broader schemes of biopolitical control that have been at play in the U.S. since the late 1970s, when previously apolitical evangelical Christians were drawn into political conversations through the transformation of abortion access into a “moral issue.” Within this discourse, the politicized female body is assumed to be perpetually pre-pregnant, a muted object housing a potential subject. At abortion clinic protests, the seemingly mundane act of “exercising free speech” vocalizes not only an opposition to abortion as a medical procedure, but also an assertion of the four decades of “moral authority” that have limited access to and availability of this medical procedure through a sustained regulation of the bodily autonomy of female citizens. The fetus is animated in service of this authority through tactics that range from fetal heartbeat bans to the amplification of an “acousmatic fetus” at a North Carolina abortion clinic protest:

When it comes to anti-abortion politics, the rhetoric hinges on the making public of the internal space of the womb in order to more effectively level the male gaze (and its listening ear) at the figure of the fetus. Anti-abortion rhetoric relies on the dissolution of boundaries between the public and the private; remember that the right to an abortion was eventually won in 1973 not on the grounds of bodily autonomy but on the constitutional “right to privacy.” These boundaries perpetuate gendered divisions of space that deem public space the space of men, while relegating women to the “private space” of the home. Female-presenting bodies are therefore seen (and heard) to be out of place in public space, even when the contents of their bodies are not. And when the focus always lies on these possible contents, female-presenting bodies are always assumed to be pregnant. Their bodies come to represent what Lauren Berlant, in her 1994 essay titled “America, ‘Fat,’ the Fetus,” describes as “fetal motherhood” (147). Within this representation, the female body possesses value only through the promise of its eventual maternal status. Within a patriarchal economy of reproduction and citizenship, the female body accrues value through its capacity to sustain and revitalize “the nation”; Berlant points out that pro-life rhetoric has in its turn revitalized the female body as a symbol of nation-formation.

Berlant argues that political and cultural rhetoric in the U.S. transforms pregnant people into babies and unborn babies into full-on “persons” through this process of “fetal motherhood.” She details this process and its implications within a broader sociopolitical discourse that hinges not only on dehumanizing tactics that reduce women to objects, but on the expectation and exploitation of the all-too-human capacity for nurturing and motherhood that society demands from women. This rhetoric is meant to mobilize the figure of the fetus in what Berlant refers to as “the nationwide competition between the mother and the fetus that the fetus, framed as a helpless, choiceless victim, will always lose” since “the fetus has no voice” (150-151). Providing a voice for the fetus has been a primary tactic in anti-abortion strategies within this “competition.” Animating the fetus’s body and voice therefore always involves the erasure and silencing of the pregnant person, who, in the state of “fetal motherhood,” is flattened into an entity as two-dimensional as an anti-abortion protester’s photoshopped poster. And just as dominant narratives and vocabularies for sonic reproduction frequently neglect the gendered implications of the term, broader political concepts of “reproduction” listen more closely to the product of motherhood than to mothers themselves.

Image by Flickr user TR Haun, (CC BY-ND 2.0)

The heartbeat bans are only one component of the anti-abortion trend in the U.S., where 288 abortion restrictions have been enacted since 2010. These bills typically deny the agency of pregnant people, while affirming the moral agency of doctors and the “personhood” of embryos and fetuses. Yet that has not stopped pregnant people, and particularly pregnant people of color, from enduring punishment. The most well-known case is probably that of Purvi Patel, an Indian American woman who self-aborted in 2015 and was subsequently sentenced to 20 years in prison after an Indiana jury found her guilty of feticide (She served about a year and a half before a judge reduced her sentence to eighteen months, resulting in her release). Within the dominant hierarchy of animacy in contemporary reproductive rights, the agency of potential persons is amplified so loudly that it drowns out the agency of actual people existing in the world. Control of the sound world doesn’t just mirror visual control over bodies and the worlds they move through, it enacts new and arguably more invasive limits on these bodies. Whether clamoring for an audience on the sidewalks of public space, or quietly sonifying potential life via Doppler technology, the sounds of sonic patriarchy continue to interrupt feminist endeavors for autonomy and agency.

—

Featured Image: March for Life, Washington DC 2015 by Flickr User American Life League, (CC BY-NC 2.0)

—

Rebecca Lentjes is an NYC-based writer and gender equality activist. Her work has appeared in VAN Magazine, Music & Literature, TEMPO Quarterly Review of New Music, Bachtrack, and I Care If You Listen. By day she researches anti-abortion protests as an ethnomusicology PhD student at Stony Brook University and works as an editor and translator at RILM Abstracts of Music Literature; by night she hatches schemes to dismantle the patriarchy.

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, check out:

A Tradition of Free and Odious Utterance: Free Speech & Sacred Noise in Steve Waters’s Temple–

Gabriel Salomon Mindel and Alexander J. Ullman

Gendered Sonic Violence, from the Waiting Room to the Locker Room–Rebecca Lentjes

Sounding Out! Podcast #63: The Sonic Landscapes of Unwelcome: Women of Color, Sonic Harassment, and Public Space–Locatora Radio

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig: