Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

Inspired by the recent Black Perspectives “W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150” Online Forum, SO!’s “W.E.B. Du Bois at 150” amplifies the commemoration of the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Du Bois’s birth in 2018 by examining his all-too-often and all-too-long unacknowledged role in developing, furthering, challenging, and shaping what we now know as “sound studies.”

It has been an abundant decade-plus (!!!) since Alexander Weheliye’s Phonographies “link[ed] the formal structure of W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk to the contemporary mixing practices of DJs” (13) and we want to know how folks have thought about and listened with Du Bois in their work in the intervening years. How does Du Bois as DJ remix both the historiography and the contemporary praxis of sound studies? How does attention to Du Bois’s theories of race and sound encourage us to challenge the ways in which white supremacy has historically shaped American institutions, sensory orientations, and fields of study? What new futures emerge when we listen to Du Bois as a thinker and agent of sound?

Over the next two months, we will be sharing work that reimagines sound studies with Du Bois at the center. Pieces by Phillip Luke Sinitiere, Kristin Moriah, Aaron Carter-Ényì, Austin Richey, Jennifer Cook, Vanessa Valdés, and Julie Beth Napolin move us toward an decolonized understanding and history of sound studies, showing us how has Du Bois been urging us to attune ourselves to it. To start the series from the beginning, click here.

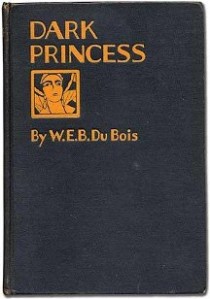

Readers, today’s post by Kristin Moriah looks at DuBois’s novel Dark Princess, and explores the relationship between sound and freedom in the text.

–Jennifer Lynn Stoever and Liana Silva, Eds.

Summer is come with bursting flower and promises of perfect fruit. Rain is rolling down Nile and Niger. Summer sings on the sea where giant ships carry busy worlds, while mermaids swarm the shores. Earth is pregnant. Life is big with pain and evil and hope. Summer in blue New York; summer in gray Berlin; summer in the real heart of the world!

W.E.B. Du Bois, Dark Princess (1928)

It is summer in Harlem now. Thick blankets of heat roil the city, and the pavement shimmers. Even the most die-hard city dwellers try to create distance between themselves and the noisy streets where political tensions threaten to boil over this season, as they always seem to. Airy tunes are often sung in vain here. More often than not, summer in New York City can be characterized by the sounds of the protests Julie Beth Napolin writes about so powerfully. At the moment, many of those protests are directed towards immigration detention centers and against forced family separation policies. Harlem, long a nexus for African diasporic and Latinx immigration and culture, has become a site of forced migration for migrant children separated from their families at the U.S. border and relocated to foster shelters like East Harlem’s Cayuga Center. Thus, contemporary nostalgia for Harlem as a site of creative freedom can be belied by reality.

But is there another place like this, not here, where one can go? An urban metropolis where one can be more attuned to sounds of the city and cries for justice? Where summer sings songs of freedom? Historically, there have been other options, especially for black travelers and migrants, and those options can tell us much about the way African American writers have conceptualized the relationship between sound and freedom. There was a strong correlation between sound and travel for African American intellectuals and performers during the Harlem Renaissance. During the brief period between Reconstruction and World War II, Europe, particularly Berlin, presented African Americans who traveled abroad with opportunities to hear and be heard differently. In The Sonic Color Line (2016), Jennifer Stoever has argued that W.E.B. Du Bois’s attention to the problem of the color line should inform our understanding of the centrality of sound in U.S. racial formations. But what happens to perceptions of the sonic color line once you cross the U.S. border? How have African American writers reflected on the sonic color line from a distance? W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1928 novel Dark Princess is an ideal place to begin exploring these questions.

W.E.B. Du Bois fictionalized the experience of traveling to Berlin at the turn of the 20th century. As a whole, his work on travelling in Europe while black contributes to the discourse around race and sound by illustrating the importance of sounding blackness to political discourse. Du Bois continually accounted for sound in both his prose and fiction about his European travels during the early 20th century. For instance, in his autobiography Darkwater, Du Bois writes “as a student in Germany, I built great castles in Spain and lived therein. I dreamed and loved and wandered and sang; then after two long years I dropped suddenly back into ‘nigger’—hating America!” (16). Here and elsewhere, Du Bois portrays singing, performing, and listening–or what I identify here as sounding blackness–as crucial activities that foster intellectual development, creativity, and political awareness. In “Death Wish Mixtape,” Regina Bradley observes that contemporary instances of sounding blackness in popular culture are often linked to commodification and death. But the act of sounding blackness can be pliable, even as it signifies keen political awareness. In the Harlem Renaissance, sounding blackness was linked to black internationalism. In Du Bois’s work, sounding blackness involves testing the limits of blackness abroad and making African American culture audible by introducing blackness into political discourse for progressive purposes.

In the opening epigraph of the novel Dark Princess, at the beginning of this post, a summer journey begins with a song in the wake of tragedy. Written during the height of the Harlem Renaissance, in W.E.B. Du Bois’s Dark Princess, African American hero Matthew Towns travels to Europe to heal himself from racism’s psychic wounds, macroagressions, and foreshortened career prospects. Like Du Bois, Towns seeks respite from the systemic racism he encounters in the U.S. educational system, in this case at the University of Manhattan, a fictional Harlem medical school that is a stone’s throw from the City University of New York’s City College. In other words, Towns is a refugee of American racism.

Matthew Towns experiences new forms of freedom when he travels abroad. Fin-de-Siècle Berlin’s ambiguous racial boundaries allow Matthew Towns to practice American citizenship, perform an unfettered African American identity, and act as a spokesperson for the first time. Faced with the question of whether African diasporic “blood must tell,” or reveal its weaknesses through inarticulate discourse, Towns boldly asserts that it won’t tell “unless it is allowed to talk. Its speech is accidental today” (22). He begins to advocate for African Americans using various performative modes. Du Bois depicts Towns as what Alex Black might term a “resonant body,” a performer who uses embodied sound to shape the viewers’ perceptions of his or her humanity. In Berlin, Towns becomes a resonant body who sounds blackness outside the boundaries of the American color line in an attempt to ameliorate conditions for African Americans at home. As such, Towns echoes Du Bois’ insistence on the importance of song to the African American tradition and socio-political ambitions in The Souls of Black Folk (1903). Thus, Dark Princess picks up on the sonic themes Du Bois proposed in his earlier works.

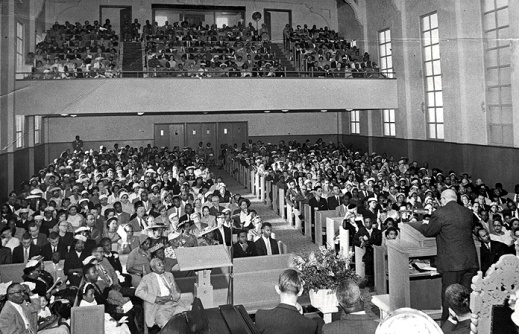

As Du Bois’s novel unfolds, readers learn how Berlin could both confound and appeal to the African American imagination as a utopic site of black performance. Towns sings to a multi-ethnic group of elite political activists at a dinner party in Berlin. Invited by Princess Kautilya of Bwodpur, at first, “Matthew felt his lack of culture audible, and not simply of his own culture, but of all the culture in white America which he had unconsciously and foolishly, as he now realized made his norm” (24). Initially, American racism prevents Towns from sounding blackness and participating in global discourses around race and freedom. And yet, at the same party in Berlin, Towns is also overcome by the memory of Negro spirituals. He becomes a resonant body by reclaiming black working-class sensibility and pride: “it was as if he had faced and made a decision, as though some great voice, crying and reverberating within his soul, spoke for him and yet was him” (23). For Matthew Towns, sounding blackness abroad is not just personally empowering; sounding allows him to imagine himself as a key contributor to larger social movements and, potentially, black liberation. In both examples, the acts of hearing, verbalizing, and singing are depicted as necessary modes of political awareness and engagement. Without access to these sonic forms, Matthew is divorced from meaningful political participation.

Eventually, Matthew finds his way into the conversation by making a powerful argument for the cultural achievements of African Americans, or “the black rabble of America,” (26) by way of Negro Spirituals: “silence dropped on all, and suddenly Matthew found himself singing. His voice full, untrained but mellow, quivered down the first plaintive bar…” (26). It is the most striking instance of black performance in the novel:

The blood rushed to Matthew’s face. He threw back his head and closed his eyes, and with the movement, he heard again the Great Song. He saw his father in the old log church by the river, leading the moaning singers in the Great Song of Emancipation. Clearly, plainly he heard that mighty voice and saw the rhythmic swing and beat of the thick brown arm. Matthew swung his arm and beat the table; the silver tinkled. (25)

Du Bois continues: “He forgot his audience and saw only the shining river and the bowed and shouting throng […] Then Matthew let go of restraint and sang as his people sang in Virginia, twenty years ago. His great voice, gathered in one long deep breath, rolled the Call of God” (26).

Towns’s newfound ability to sound blackness in Berlin, or in other words vocalize African American claims to citizenship and freedom, stand in contrast to his earlier inability to respond coherently to Northern racism in New York City, where he is left “sputtering with amazement” at his exclusion from a medical school at which he has rightfully earned his place. In that instance, Matthew is rendered speechless. When “his fury had burst its bounds” it resulted in not a stream of invectives or vain pleas for justice, but a physical response. He throws “his certificates, his marks, and commendations straight into the drawn white face of the Dean” (4). Afterwards, isolated and alone, he stalks New York City. If there is a distinct sonic dimension to this flight from discrimination, readers are not privy to it. The sounds of Matthew’s footsteps, and cries of righteous indignation, fade into the background of Harlem’s streets. They are perhaps indiscernible amidst the ebb and flow of any number of similar city sounds and experiences. In this instance, Du Bois seems to suggest that the sound that emanates from physical gestures loses potency in certain urban contexts.

When Matthew Towns returns to Harlem, we are told that it’s with a renewed ear and life purpose. Standing on Seventh Avenue, with City College to his left, “he turned east and the world turned too – to a more careless and freer movement, louder voices and easier camaraderie” (41). From the sounds of church music to the accents of West Indian immigrants, he is much more attuned to the city’s diverse African diasporic presence. Hearing these African diasporic connections in a new way, he is fueled for black leadership and political activism.

Thus, Towns’s experiences sounding blackness abroad are a pivotal step in his political awakening and activism on U.S. soil. In locating the project of sounding blackness between Harlem and Berlin, Du Bois’s fiction makes space for the privileged summer traveler, the forced migrant, and immigrant. All are bound by the desire for social progress on local and global scales. Finally, I argue that the dynamic relationship between sound, space, justice and travel that Du Bois maps out has striking relevance to contemporary political and ethical crises. As in Dark Princess, justice in the here and now can be measured by the ability to sound aloud and effect social change the world over and on street corners.

—

Featured image: “Mapping Courage” by Flickr user Laurenellen McCann, CC BY-NC 2.0

—

Kristin Moriah is an Assistant Professor of African American Literary Studies in the English Department at Queen’s University. She is the editor of Black Writers and the Left (Cambridge Scholars Press, 2013) and the co-editor of Adrienne Rich: Teaching at CUNY, 1968-1974 (Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, 2014). Her work can be found in American Quarterly, PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, Theater Journal, and Understanding Blackness Through Performance (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). Her research has been funded through grants from the Social Science and Humanities Council of Canada, the Freie Universität Berlin, the CUNY Graduate Center’s Advanced Research Collaborative and the Harry Ransom Center. In spring 2015 Moriah was a Scholar-in-Residence at the NYPL Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Black Mourning, Black Movement(s): Savion Glover’s Dance for Amiri Baraka –Kristin Moriah

“Most pleasant to the ear”: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Itinerant Intellectual Soundscapes — Phillip Luke Sinitiere

The Noise You Make Should Be Your Own–Scott Poulson-Bryant

This is not new to me. Both my artistic work and a number of my scholarly works have been purposely ignored or undermined in previous occasions, perhaps due to my non-white, non-European background and epistemology. During the assessment of my doctoral dissertation in a well-known Scandinavian University, for example, the three-member committee harshly attacked the very foundations of my project because of my claim that case studies in Indian cinema could produce important new knowledge in the field of sound studies, media art and film history. However, Indian cinema, the largest producer of films in the global industry, is equally a part of world cinema as European and American cinemas, and studying its sound production would indeed add dimensions to the field of sound studies. Their resistance towards my object of study implied that choosing European cinema would immediately make my hypotheses acceptable.

This is not new to me. Both my artistic work and a number of my scholarly works have been purposely ignored or undermined in previous occasions, perhaps due to my non-white, non-European background and epistemology. During the assessment of my doctoral dissertation in a well-known Scandinavian University, for example, the three-member committee harshly attacked the very foundations of my project because of my claim that case studies in Indian cinema could produce important new knowledge in the field of sound studies, media art and film history. However, Indian cinema, the largest producer of films in the global industry, is equally a part of world cinema as European and American cinemas, and studying its sound production would indeed add dimensions to the field of sound studies. Their resistance towards my object of study implied that choosing European cinema would immediately make my hypotheses acceptable. In his essay “

In his essay “

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Samantha Ege

Samantha Ege REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig: