Limn is proud to announce the release of Limn 10: Chokepoints in gorgeous print and PDF versions. Your purchase of either a handsome matte-finished, 8×10, coffee-table-worthy version ($25) or a tablet-beautifying PDF ($5 or your reserve price) all goes to making more Limn possible. Limn is non-profit, scholar-run, and open access, but we believe in making a beautiful vessel for our ideas. Get one today!

Everyone’s Going to the Rumba: Trap Latino and the Cuban Internet

In “Asesina,” Darell opens the track shouting “Everybody go to the discotek,” a call for listeners to respond to the catchy beat and come dance. In this series on rap in Spanish and Sound Studies, we’re calling you out to the dance floor…and we have plenty to say about it. Your playlist will not sound the same after we’re through.

In “Asesina,” Darell opens the track shouting “Everybody go to the discotek,” a call for listeners to respond to the catchy beat and come dance. In this series on rap in Spanish and Sound Studies, we’re calling you out to the dance floor…and we have plenty to say about it. Your playlist will not sound the same after we’re through.

Throughout January, we will explore what Spanish rap has to say on the dance floor, in our cars, and through our headsets. We’ll read about Latinx beats in Australian clubs, and about femme sexuality in Cardi B’s music. And because no forum on Spanish rap is complete without a mixtape, we’ll close out our forum with a free playlist for our readers. Today we start No Pare, Sigue Sigue: Spanish Rap & sound Studies with Michael Levine’s essay on Trap cubano and el paquete semanal.

-Liana M. Silva, forum editor

—

Trap Latino has grown popular in Cuba over the past few years. Listen to the speakers blaring from a young passerby’s cellphone on Calle G, or scan through the latest digital edition of el paquete semanal (the weekly package), and you are bound to hear the genre’s trademark 808 bass boom in full effect. The style however, is almost entirely absent from state radio, television, and concert venues. To the Cuban state (and many Cubans), the supposed musical and lyrical values expressed in the music are unacceptable for public consumption. Like reggaetón a decade before, the reputation of Trap Latino (and especially the homegrown version, Trap Cubano) intersects with contemporary debates regarding the future of Cuba’s national project. For many of its fans however, the style’s ability to challenge the narratives of the Cuban state is precisely what makes Trap Latino so appealing.

In an article published last year by Granma (Cuba’s official, state-run media source), Havana-based journalist Guillermo Carmona positions Trap Latino artists like Bad Bunny and Bryant Myers as a negative influence on Cuba’s youth, claiming the music sneaks its way into the ears of unsuspecting Cuban youth via the illicit channels of Cuba’s underground internet. With lyrics that celebrate the drug trade and treat women as “slot machines,” coupled with a preponderance of sound effects instead of “music notes,” Carmona considers Trap Latino aggressive, dangerous, and perhaps most perniciously of all, irredeemably foreign.

Towards the end of the article, Carmona focuses on his biggest concern: the performance of Trap Latino in public spaces. Carmona writes of those who play Trap from sound systems that “…they use portable speakers and walk through the streets (dangerously), like a baby driving a car. The combat between the bands that narrate some of these songs gestures towards another battlefield: the public sound space.” For Carmona, this public battlefield is sonically marked by Trap Latino’s encroachment on Cuba’s hallowed musical turf. His complaints highlight the fact that this Afro-Latinx style largely exists in Cuba on one side of what Jennifer Lynn Stoever refers to as the sonic color line, an “interpretive and socially constructed practice conditioned by historically contingent and culturally specific value systems riven with power relations” (14).

In Cuba, historically constructed power relations are responsible for much of the public reception of Afro-Cuban popular music, including rumba, timba, and reggaetón. But Trap Latino’s growing presence on the digital devices of Cuban youth is reshaping the boundaries of Cuba’s sonic color line. While these traperos are generally unable to perform in public (due to strict laws governing uses of Cuba’s public spaces) their music is nonetheless found across Havana’s urban soundscape, thanks to the illicit, but widespread, distribution of the “Cuban Internet.”Historically marginalized Afro-Cuban artists, like Alex Duvall, are today using creative digital strategies to make their music heard in ways that were impossible just a decade ago.

The Cuban Internet

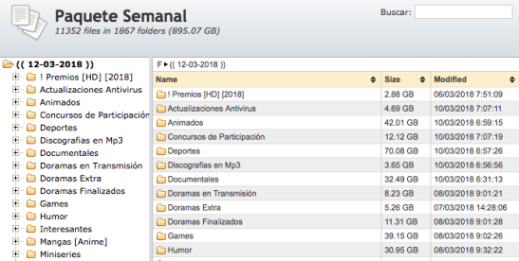

To get around the lack of an internet infrastructure either too costly, or too difficult to access, Cubans have developed a network for trading digital media referred to as “el paquete semanal,” contained on terabyte-sized USB memory sticks sold weekly to Cuban residents. These memory sticks contain plenty of content: movies, music, software applications, a “Craiglist”-styled bulletin board of local products for sale, and even an offline social network, among others. The device is traded surreptitiously, presumably without the knowledge of the state.

(There is some question surrounding the degree at which the state is unaware of the paquete trade. Robin Moore, in Music and Revolution, refers to the Cuban government’s propensity to selectively enforce certain illegalities as “lowered frequency”. Ex-president Raul Castro has publicly referred to the device as a ‘necessary evil,” suggesting knowledge, and tacit acceptance, of the device’s circulation.)

By providing a means for artists to circulate products outside of state-sanctioned channels of distribution, el paquete semanal greatly broadens the range of content available to the Cuban public. The importance of the paquete to Cuba’s youth cannot be overstated. According to Havana-based journalist José Raúl Concepción, over 40% of Cuban households consume the paquete on a weekly basis, and over 80% of citizens under the age of 21 consume the paquete daily. A high percentage of the music contained on these devices is not played on the radio or seen in live concerts. For many Cubans, it is only found in the folders contained on these devices. The paquete trade therefore, serves as an invaluable barometer of music trends, especially those of younger people who represent the largest number of consumers of the device.

A listing of folders on el paquete semanal from October 30, 2018.

Alex Duvall

There is a random-access, mix-tape quality to the paquete that encourages consumers to discover music by loading songs onto their cellphones, shuffling the contents, and pressing play (a practice as common in Cuba as it is in the US). This mode of consumption encourages listeners to discover music to which they otherwise would not be exposed. Reggaetón/Trap Latino artist Alex Duvall takes advantage of this organizing structure to promote his work in a unique manner: Duvall packages his reggaetón music separately from his Trap Latino releases. As a solo act, his reggaetón albums position catchy dembow rhythms alongside lyrics and videos that celebrate love of nation, Cuban women, and Havana’s historic landmarks. As a Trap Latino artist in the band “Trece,” his brand is positioned quite differently. Music videos like Trece’s “Mi Estilo de Vida” for instance, contain many of the markers that journalist Guillermo Carmona criticized in the aforementioned article: a range of women wear the band’s name on bandanas covering their faces, otherwise leaving the rest of their bodies exposed. US currency floats in mid-air, and lyrics address the pleasures of material comforts amid legally questionable ways of “making it.”

Especially as it becomes more and more common for Latinx artists to mix genres freely together in their music (as the catch-all genre format referred to as música urbana shows), it is significant that Alex Duvall prefers to keep these styles separate in his own work. The strategy reveals a musical divide between foreign and domestic elements. Duvall’s reggaetón releases emphasize percussive effects, and the Caribbean-based “dembow riddim” that many Cubans would quickly recognize. The synthesized elements in his Trap Latino work however, belong to an aesthetic foreign to historic representations of Cuban music, representing broader circulations of sound that now extend up to the US. Textures and rhythms originating from Atlanta (along with their attendant political and historical baggage) now share space in the sonic palette of a popular Cuban artist.

Going to the Rumba

These cultural circulations complicate narratives coming from the Cuban state that tend to minimize the cultural impact of music originating from the yankui neighbor to the north. These narratives exert powerful political pressure. Because of this, artists are careful when describing their involvement with Trap music. Duvall’s digital strategy allows for a degree of freedom in traveling back and forth across the sonic color line, but permits only so much mobility.

In an interview conducted by MiHabanaTV, Duvall distances himself from Trap Latino’s reputation, defending his project by appealing to the genre’s international popularity, and the need to bring it home to Cuba. But the 2017 song “Hasta La Mañana” documents one of his most concise explanations for his involvement in Trece, in the following lyrics:

| “El tiempo va atando billetes a cien Pero todos va para la rumba Entonces yo quiero sumarme tambien.” |

Time is tying hundred dollar bills together Everyone is going to the rumba And I also want to join. |

He uses “rumba” here as shorthand to refer to the subversive actions that people take in order to succeed in difficult situations. Duvall needs to make money. If everyone else gets rich by going to “the rumba,” why can’t he? The reference is revealing. Rumba marks another Afro-Cuban tradition with a history of marginalized figures engaged in debates over appropriate aural uses of public space. Today, cellphone speakers and boom boxes sound Havana’s parks and streets. Historically, Afro-Cuban rumberos made these spaces audible through live performance, but similar issues of race animate both of these moments.

In the essay “Walking,” sociologist Lisa Maya Knauer explains that it was not uncommon for police to break up a rumba being performed in the streets or someone’s home throughout the twentieth century “on the grounds that it was too disruptive.” (153) Knauer states that rumba music is historically associated with “rowdiness, civil disorder, and unbridled sexuality, while simultaneously celebrated as an icon of national identity”. (131) The quote also reveals a contrast between the public receptions of rumba and Trap Latino. Duvall’s work, and Trap Latino more generally, is similarly fixed amid a complex web of racialized associations. But unlike rumba, refuses to appeal to state-sanctioned ideals of national identity.

Afro-Cuban musicians are often pressured to adopt nationally sanctioned modes of participation in order to acquire official recognition and state funding. The acceptable display of blackness in Cuba’s public spaces, especially while performing for the country’s growing number of tourists, is a process that anthropologist Marc D. Perry calls the “buenavistization” of Cuba in his work Negro Soy Yo. This phrase refers to the success of popular Son heritage group Buena Vista Social Club, and the revival of Afro-Cuban heritage musical styles that this group and its associated film popularized. Unlike Rumba and Son however, Trap Latino is considered irredeemably foreign (given its roots in both the US city of Atlanta and later, Puerto Rico), therefore presenting difficulties in assimilating the genre to dominant models of Cuban national identity. This tension, I believe, is also responsible for it’s success among Cuba’s youth.

Trap Cubano’s growing appeal stems instead from artists’ adoption of a radically counter-cultural positionality often avoided in popular contemporary styles like reggaetón. While it would be unfair to accuse reggaetón as being entirely co-opted (a point musicologist Geoff Baker makes convincingly in “Cuba Rebelión: Underground Music in Havana”), it is certainly true that as reggaetóneros achieve greater success in ever widening circles of international popularity, the amount of scandalized lyrics, eroticized imagery, and the sound of the original dembow riddim itself (with its well documented roots in homophobia and virulent masculinity) has diminished considerably. Trap Latino’s sonic subversions fill this gap. While the genre similarly praises the fulfillment of male, material fantasies, it troubles the narrative that increased access to money solves social, racial, and gender imbalances, while sonically acknowledging the role that the US shares in shaping it’s musical terrain.

This centering of materialism amid representations of marginalized Afro-Cuban artists is foreign to both historic and touristic representations of Cuba, but relevant to a younger generation increasingly confronted with the pressures of encroaching capitalism. Trap Cubano renders visible (and audible) an emerging culture managing life on the less privileged side of the sonic color line. From the speakers blaring from a young passerby’s cellphone on Calle G, to the USB stick plugged in to a blaring sound system, to the rumba where Alex Duvall is headed, Trap Latino broadcasts the concerns of a younger generation challenging what it means to be Cuban in the 21st century, and what that future sounds like.

—

Involving himself in the music scenes of Brooklyn, N.Y. over the past decade, Mike Levine has utilized a dual background in academic research and web-based application technologies to support sustainable local music scenes. His research now takes him to Cuba, where he studies the artists and fans circulating music in this vibrant and fast-changing space via Havana’s USB-based, ‘people-powered’ internet (el paquete semanal) amidst challenging political and economic circumstances.

—

Featured image: “Hotel Cohiba – Havana, Cuba” by Flickr user Chris Goldberg, CC BY-NC 2.0

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Spaces of Sounds: The Peoples of the African Diaspora and Protest in the United States–Vanessa Valdes

SO! Reads: Shana Redmond’s Anthem: Social Movements and the Sound of Solidarity in the African Diaspora–Ashon Crawley

Music Meant to Make You Move: Considering the Aural Kinesthetic– Imani Kai Johnson

Principles of ‘Good Data’

Good Data edited by Angela Daly, S. Kate Devitt and Monique Mann will be published by INC in January 2019. The book launch will be 24 Januari @ Spui25. In anticipation of the publication, we publish a series of posts by some of the authors of the book.

“Moving away from the strong body of critique of pervasive ‘bad data’ practices by both governments and private actors in the globalized digital economy, this book aims to paint an alternative, more optimistic but still pragmatic picture of the datafied future. The authors examine and propose ‘good data’ practices, values and principles from an interdisciplinary, international perspective. From ideas of data sovereignty and justice, to manifestos for change and calls for activism, this collection opens a multifaceted conversation on the kinds of futures we want to see, and presents concrete steps on how we can start realizing good data in practice.”

The ‘Good Data’ Project

By S. Kate Devitt, Monique Mann and Angela Daly

The Good Data project was initiated by us when we were all based together at Queensland University of Technology (QUT) in Brisbane/Meanjin – located on traditional Turrbal and Jagera land in what is now known as Brisbane, Australia – in late 2017. Each of us had been working on research engaging with social science aspects of data and digital technologies, and Angela and Monique had also been very active in digital rights activism. The situation in Australia was then, and still is, far from ‘best practice’ in data and digital issues. Australia lacks an enforceable constitutional right to privacy, the Australian government exhibits ongoing digital colonialism perpetuated against Indigenous peoples, refugees and other marginalised people and there are a myriad of other unethical data practices being implemented (e.g., robo-debt fiasco, #censusfail and the ‘war on maths’. However, these issues are not only confined to Australia – ‘bad’ data practices permeate the digital society and economy globally.

While we had spent a lot of time and energy criticising bad data practices from both academic and activist perspectives, we realised that we had not presented an alternative more positive alternative. This became our main focus, leading us to consider the idea of what this positive vision of data could look like. The concept of ‘Good data’ was first interrogated in a good data workshop bringing together interdisciplinary academics, activists, information consultants, and then through soliciting contributions to a book on Good Data about to be published by the Institute of Network Cultures in Amsterdam.

In this blog post we present some of the lessons that we have taken away from the Good Data project. Many of the contributions we received for the book advocated data methods to dismantle existing power structures through the empowerment of communities and citizens. We have synthesised the contributions to present 15 (preliminary) principles of Good Data. Of course all principles are normative and their exact meaning and application differ dependent on context (particularly as regards to tensions between open data and data protection and privacy) – although these context-dependent distinctions should be fairly obvious.

Data for challenging colonial and neoliberal data practices

The first Good Data principle we advance is a critique of colonial and neoliberal data practices, economic systems and capitalist relations. In their Good Data book chapter Indigenous Data Sovereignty (IDS) scholars and advocates Lovett and colleagues examined how western-colonial data practices affect self-determination and autonomy within Indigenous and First Nations groups that have been subject to various forms of data domination. Their findings relate to the first Good Data principle:

Principle #1: Data collection, analysis and use must be orchestrated and mediated by and for data subjects, rather than determined by those in power.

Account must be taken of the specificities of particular data subjects and their communities, cultures and histories. Indigenous Data Sovereignty principles may overlap with aspects of western data protection laws but may also impose different and additional requirements beyond this legislation, which reflect First Nations peoples’ own laws and sovereignty rights.

In another contribution to the Good Data book, Ho and Chuang critique neoliberal data protection models which emphasize individual autonomy and choice through concepts such as consent and anonymization – indeed, this is an argument that has previously been made in the data protection literature. Instead, they propose that communal data sharing models present a good data alternative to the current widespread proprietary and extractive models. This would mean moving towards data cooperatives where the value of data, and the governance of the system, is shared by data subjects.

Principle #2 Communal data sharing can assist community participation in data related decision-making and governance.

Such an approach presents an alternative means of governing and using data based on data subjects’ participation and power over their own data, and also moves away from an individualistic approach to data ownership, use and sharing, presenting a paradigm shift from the current extractive model which leaves data subjects largely powerless regarding meaningful control over their own data.

As part of a bigger discussion around use of data for societal sustainability, Kuch and colleagues argue that individuals and collectives should have access to the data about the energy they produce and consume (e.g. solar) to hasten take-up and implementation of sustainable energy in a sustainable, communal way. This also relates to principle 2 above as regards to communal data sharing and community participation in decision-making and governance.

Principle #3 Individuals and collectives should have access to their own data to promote sustainable, communal living.

Data for empowering citizens

The second set of principles we consider concern methods for empowering citizens against governments and corporations that use data for social control and to perpetuate structural inequalities. Poletti and Gray suggest that Good Data can be used to critique power dynamics associated with the use of data, and with a focus on economic and technological environments in which they are generated.

Principle #4 Good data reveals and challenges the political and economic order.

Good Data can also improve the landscape for citizens vis-à-vis governments and corporations. One example can be found in Ritsema van Eck’s chapter where he argues that data in smart cities needs to undergo Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) to identify risks at an early stage. These should be consultative so that representatives of local (disadvantaged) groups and citizen groups can proactively shape the environments in which they live. Valencia and Restrepo also argue for citizen-led data initiatives to produce bottom-up smart cities instead of top-down controlled environments. Taken together and at a higher level of abstraction, our fifth principle is that inclusive and citizen-led social data practices empower citizens, encompassing Good Data process and Good Data outcomes.

Principle #5 Citizen led data initiatives lead to empowered citizens.

Ozalp, among many other authors including ourselves, argues for strong information security to support citizen activism to produce good democracies using the case study of the ByLock persecutions in Turkey. In this way, Good Data can contribute to achieving broader societal goals such as good democracy.

Principle #6 Strong information security, online anonymity and encryption tools are integral to a good democracy.

Open data is also a Good Data way of empowering citizens. Gray and Lämmerhirt examined how the Open Data Index (ODI) influences participation and data politics, comparing indexes to the political mobilization afforded by rallies, petitions and hashtags.

Principle #7 Open data enables citizen activism and empowerment.

Good Data does not have to be perfect data though. Gutiérrez advocates for ‘good enough data’ to progress social justice issues, i.e. the provision of sufficient data to sustain ongoing legal investigations while deficits are acknowledged (see her blog post on this).

Principle #8 Social activism must proceed with ‘good enough data’ to promote the use of data by citizens to impose political pressure for social ends.

Data for Justice

The third set of principles specifically relate to how data intersects with various conceptions of justice. Bosua and colleagues argue that users should be able to exert greater control over the collection, storage and use of their personal data. Personal data empowerment can be achieved through design that make data flows more transparent to users.

Principle #9 Users must be able to understand and control their personal data.

Societal changes from reliance on connected devices within groups is examined by Flintham and colleagues research on interpersonal data. They note specific issues that arise when personal information is shared with other members and has consequences for the ongoing relationships in intimate groups.

Principle #10: Data driven technologies must respect interpersonal relationships (i.e. data is relational).

As regards to genomic data Arnold and Bonython argue data collection and use must embody respect for human dignity which ought to manifest, for instance, in truly consensual, fair and transparent data collection and use. This also relates to sovereignty and control over data – whether individual or group.

Principle #11 Data collection and use must be consensual, fair and transparent.

McNamara and colleagues examined algorithmic bias in recidivism prediction methods with the objective of identifying and rectifying racial bias perpetuated in the criminal justice system. In doing so they argue that criterions and meanings of ‘fairness’ (and by extension other values) attributed to data or that are adopted in models should be explicit. What looks ‘fair’ or ‘just’ to a computer scientist looks different to a philosopher or a criminologist – that is, there are subjective meanings of ‘goodness’, and these should be explicit to enable evaluation.

Principle #12 Measures of ‘fairness’ and other values attributed to data should be explicit.

Good data practices

Trenham and Steer set out a series of ‘Good Data’ questions that data producers and consumers should ask, constituting three principles which can be used to guide data collection, storage, and re-use, including:

Principle #13 Data should be usable and fit for purpose.

Principle #14 Data should respect human rights and the natural world.

Data collection structures, processes and tools must be considered against potential human rights violations and impacts on the natural world, including environmental (e.g. the energy impacts of mining cryptocurrencies).

Principle #15 Good data should be published, revisable and form useful social capital where appropriate to do so.

Good data should be open to enable the data activism and the communal data sharing practices outlined above unless there are ethical reasons to withhold this information. We acknowledge the tension between open data and misuse of this data by institutions, corporations and governments to protect and retain power. Principle #6 defends security and encryption and principle #9 ensures individual’s rights to their own data that must be considered aligned with and the broader goal of communal data practices discussed throughout.

In sum, Good Data must be orchestrated and mediated by and for data subjects (Principle 1), including communal sharing for community decision-making and self-governance (Principle 2, 3). Good Data should be collected with respect to humans and their rights and the natural world (Principle 14). It is usable and fit for purpose (Principle 13); consensual, fair and transparent (Principle 9, 11 & 12), and must respect interpersonal relationships (Principle 10). Good data reveals and challenges the existing political and economic order (Principle 3) so that data empowered citizens can secure a good democracy (Principle 5, 6, 7, 8). Dependent on context, and with reasonable exceptions, Good Data should be open / published, revisable and form useful social capital (Principle 15).

We look forward to launching the Good Data book which includes the contributions we have drawn on above, and more, in late January 2019. Join us at our book launch on 24 January 2019 at Spui 25 in Amsterdam.

Forthcoming Good Data Chapters in A Daly, SK Devitt & M Mann (eds), Good Data. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures.

Arnold, B. & Bonython, W. (2019). Not as Good as Gold? Genomics, Data and Dignity.

Bosua, R., Clark, K., Richardson, M. & Webb, J. (2019). Intelligent Warming Systems: ‘Technological Nudges’ to Enhance User Control of IoT Data Collection, Storage and Use.

Flintham, M., Goulden, M., Price, D., & Urquhart, L. (2019). Domesticating Data: Socio-Legal Perspectives on Smart Homes and Good Data Design.

Gray, D. & Lämmerhirt, D. Making Data Public? The Open Data Index as Participatory Device.

Gutierrez, M. (2019). The Good, the Bad and the Beauty of ‘Good Enough Data’.

Ho, CH. & Chuang, TR. (2019). Governance of Communal Data Sharing.

Kuch, D., Stringer, N., Marshall, L., Young, S., Roberts, M., MacGill, I., Bruce, A., & Passey, R. (2019). An Energy Data Manifesto.

Lovett, R., Lee, V., Kukutai, T., Cormack, D., Carroll Rainie, S., & Walker, J. (2019). Good data practices for Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance.

Poletti, C. & Gray, D. (2019). Good Data is Critical Data: An Appeal for Critical Digital Studies.

Ritsema van Eck, G. (2019). Algorithmic Mapmaking in ‘Smart Cities’: Data Protection Impact Assessments as a means of Protection for Groups.

Trenham, C. & Steer, A. (2019). The Good Data Manifesto.

Valencia, JC. & Restrepo, P. (2019). Truly Smart Cities. Buen Conocer, Digital Activism and Urban Agroecology in Colombia.

SO! Amplifies: Phantom Power

Phantom Power is an aural exploration of the sonic arts and humanities, that launched in March 2018 with Episode 1: Dead Air (John Biguenet and Rodrigo Toscano) Hosted by poet + media artist cris cheek and sound + media scholar Mack Hagood, this podcast explores the sounds and ideas of artists, technologists, producers, composers, ethnographers, historians, cultural scholars, philosophers, and others working in sound. Because Phantom Power is about to kick off its second season on February 1, 2019, we thought we’d dig a little deeper into who they are and who they’d like to reach with their good vibrations.

Funded through a generous grant from the Miami University Humanities Center and The National Endowment for the Humanities, Phantom Power was created with the goal of bringing together three important streams of conversation in the humanities

(1) diverse and interdisciplinary scholarly pursuits, taking place under the umbrella of “sound studies,” that analyze and critique the sonic entanglements and practices of human beings;

(2) experimental aesthetic practices that use sound as a medium and inspiration to expand the boundaries of art, music, and poetry;

and (3) the nascent use of podcasting as a mode of scholarship, intra-/interdisciplinary communication, and public outreach.

The public-facing podcast draws on the extensive radio experience of co-host cris cheek, creator of Music of Madagascar, made for BBC Radio 3 in 1994, which won the SONY GOLD AWARD, Specialist Music Program of the Year. In 1998 he made crowding, a three and a half hour live-streamed webcast of largely improvised speech and sound events, commissioned as part of Torkradio from by Junction Multimedia in Cambridge. In 2004, cheek was part of the BBC series Between the Ears, on the subject of speaking in tongues, in conversation with the artist and film-director Steve McQueen, exploring the boundaries of vocal expression with actress Billie Whitelaw, and linguistics professor William Samarin. cheek appears in the first episode talking about the many contradictory experiences of “dead air” in an age of changing media technologies.

Phantom Power also alchemizes the scholarship of co-host Mack Hagood (see Hush: Media and Sonic Self-Control forthcoming in March 2019 from Duke University Press and his 2012 SO! post “Listening to Tinnitus: Roles of Media When Hearing Breaks Down”) as well as his audio production background as a musician, producer, and radio DJ—skills he has long incorporated into his scholarship and teaching. At Indiana University, for example, he and his students and won the Indiana Society of Professional Journalists’ 2012 Best Radio Use of Sound award for our documentary series “I-69: Sounds and Stories in the Path of a Superhighway.” The first episode even featured music by Hagood and by Graeme Gibson, who was touring on drums with Michael Nau and the Mighty Thread at the time. Additional sound is by Cl0v3n.

“We spend a lot of time on the production aspects of this podcast,” says Hagood, “because we want it to be a sonic and affective experience, not just an intellectual one. Many of us in sound studies have complained that we always find ourselves writing about sound. Phantom Power is our attempt to treat sound not only as an object of study, but also a means of understanding and feeling sound scholarship. This makes our show very different from most academic podcasts, which are usually lo-fi discussions between scholars about recent books. We love that kind of podcast but we build upon it by using narrative, sound design, and music to tell a compelling story that we hope will appeal to the public and sound specialists alike.”

In addition to their exploration of “dead air,” Phantom Power’s inaugural season included longform interviews with urban scholar Shannon Mattern (Episode 2, “City of Voices”), sound artist Brian House (Episode 3, “Dirty Rat”), Australia-based sound composer, media artist and curator Lawrence English (Episode 4, “On Listening In” ), and with scholar and SO! ed Jennifer Stoever (Episode 5, “Ears Racing”). The final two episodes explored what “the future will sound like” on World Listening Day (July 18th) [Episode 6: Data Streams (Leah Barclay and Teresa Barrozo) and featured Houston’s SLAB car culture [Episode 7: Screwed & Chopped (Langston Collin Wilkins)].

“I’m super excited about Season Two,” says Hagood. “Our opener stars one of my favorite sound scholars, NYU’s Mara Mills. It also uses one of my favorite formats that cris and I have developed, where one of us brings in some crazy sounds for the other to listen and react to, then we gradually develop the backstory to the sounds through our guest’s words, eventually landing on the sonic and cultural implications of it all. It’s like a fun mystery, where one co-host acts as guide and the other gets to stand in for the listener—reacting, laughing, and questioning.”

When Phantom Power returns next month, other new entries will feature cheek’s interviews with Charles Hayward of legendary experimental rock band This Heat and poet Caroline Bergvall, whose work has been commissioned by such institutions as MoMA and the Tate Modern. “I interview amazing sound scholars, but I’m a bit star struck by some of the musicians, sound artists, and poets cris interviews!” says Hagood.

You can access Phantom Power and subscribe on a plethora of outlets: itunes, android, stitcher, google podcasts, and/or by email.

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

SO! Amplifies: Ian Rawes and the London Sound Survey–Ian Rawes

SO! Amplifies: Cities and Memory–Stuart Fowkes

SO! Amplifies: #hearmyhome and the Soundscapes of the Everyday–Cassie J. Brownell and Jon M. Wargo

Good Data are Better Data

Good Data edited by Angela Daly, S. Kate Devitt and Monique Mann will be published by INC in January 2019. The book launch will be 24 Januari @ Spui25. In anticipation of the publication, we publish a series of posts by some of the authors of the book.

“Moving away from the strong body of critique of pervasive ‘bad data’ practices by both governments and private actors in the globalized digital economy, this book aims to paint an alternative, more optimistic but still pragmatic picture of the datafied future. The authors examine and propose ‘good data’ practices, values and principles from an interdisciplinary, international perspective. From ideas of data sovereignty and justice, to manifestos for change and calls for activism, this collection opens a multifaceted conversation on the kinds of futures we want to see, and presents concrete steps on how we can start realizing good data in practice.”

Good Data are Better Data

By Miren Gutierrez

Are big data better data, as Cukier argues? In light of the horror data and AI stories we witnessed in 2018, this declaration needs revisiting. The latest AI Now Institute report describes how, in 2018, ethnic cleansing in Myanmar was incited on Facebook, Cambridge Analytica sought to manipulate elections, Google built a secret [search?] engine for Chinese intelligence services and helped the US Department of Defence to analyse drone footage [with AI], anger ignited over Microsoft contracts with US’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) use of facial recognition and internal uprisings arose over labour conditions in Amazon. These platforms’ data-mining practices are under sharp scrutiny because of their impact on not only privacy but also democracy. Big data are not necessarily better data.

However, as Anna Carlson assures, “the not-goodness” of data is not built-in either. The new book Good Data, edited by Angela Daly, Kate Devitt and Monique Mann and published by the Institute of Network Cultures in Amsterdam, is precisely an attempt to demonstrate that data can, and should, be good. Good (enough) data can be better not only regarding ethics but also regarding technical needs for a given piece of research. For example, why would you strive to work with big data when small data are enough for your particular study?

Drawing on the concept of “good enough data”, which Gabrys, Pritchard and Barratt apply to citizen data collected via sensors, my contribution to the book examines how data are generated and employed by activists, expanding and applying the concept “good enough data” beyond citizen sensing and the environment. The chapter examines Syrian Archive –an organization that curates and documents data related to the Syrian conflict for activism— as a pivotal case to look at the new standards applied to data gathering and verification in data activism, as well as their challenges, so data become “good enough” to produce evidence for social change. Data for this research were obtained through in-depth interviews.

What are good enough data, then? Beyond FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable), good enough data are data which meet standards of being sound enough in quantity and quality; involving citizens, not only as receivers, but as data gatherers, curators and analyzers; generating action-oriented stories; involving alternative uses of the data infrastructure and other technologies; resorting to credible data sources; incorporating verification, testing and feedback integration processes; involving collaboration; collecting data ethically; being relevant for the context and aims of the research; and being preserved for further use.

Good enough data can be the basis for robust evidence. The chapter compares two reports on the bombardments and airstrikes against civilians in the city of Aleppo, Syria in 2016; the first by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the second by Syrian Archive[1]. The results of the comparison show that both reports are compatible, but that the latter is more unequivocal when pointing to a Russian participation in the attacks.

Based on 1,748 videos, Syrian Archive’s report says that, although all parties have perpetrated violations, there was an “overwhelming” Russian participation in the bombardments. Meanwhile, the OHCHR issued a carefully phrased statement in which it blamed “all parties to the Syrian conflict” of perpetrating violations resulting in civilian casualties, admitting that “government and pro-government forces” (i.e. Russian) were attacking hospitals, schools and water stations. The disparity in the language of both reports can have to do more with the data that these organizations employed in their reports than with the difference between a bold non-governmental organization and a careful UN agency. While the OHCHR report was based on after-the-event interviews with people, Syrian Archive relied on video evidence from social media, which were then verified via triangulation with other data sources, including a network of about 300 reliable on-the-ground sources.

The chapter draws on the taxonomy offered in my book Data activism and social change, which groups data-mining methods into five categories:

The chapter also looks into the data practices of several activist and non-activists groups to make comparisons with the Syrian Archive’s methods. The Table below offers a comparison among different data activist organizations’ data-mining methods. It shows the variety of data methods and approaches that data activism may engage / employ.

Table: Comparison of Data Initiatives by Their Origins

The interest of this exercise is not the results of the investigations in Syria, but the data and methods behind them. What this shows us is that this type of data activism is able to produce both ethically and technically good enough data to generate reliable (enough) information, filling gaps, complementing and supporting other actors’ efforts and, quoting Gabrys, Pritchard and Barratt, creating actionable evidence that can “mobilize policy changes, community responses, follow-up monitoring, and improved accountability”.

[1] The report is no longer available online at the time of writing.

Emotions Go to Work Exhibition

MediArXiv project launched!

# Call for Steering Committee Members – MediArXiv

The initial Steering Committee is excited to announce the forthcoming launch of MediArXiv, the nonprofit, open archive for media, film & communication studies. The open-access “preprint” server will soon accept submissions from scholars across our diverse fields. MediArXiv will join the growing movement started by the math/physics/computer science-oriented arXiv.org over 25 years ago, as one of the first full-fledged preprint servers conceived for humanities and social science scholars.

MediArxiv will accept working papers, pre-prints, accepted manuscripts (post-prints), and published manuscripts. The service is open to articles, books, and book chapters. There is currently some limited support for other scholarly forms (like video essays), which we plan to expand and officially support in the future.

Our aim is to promote open scholarship across media, film and communication studies around the world. In addition to accepting and moderating submissions, we plan to advocate for policy changes at the major media, film, & communication studies professional societies around the world–to push for open-access friendly policies, in particular, for the journals that these associations sponsor.

MediArXiv will launch in early 2019 on the Open Science Framework, which already hosts a number of other discipline-specific open archives:

We are writing to solicit applications for additional Steering Committee membership, with an interest in, but not limited to, early career scholars and those who work in the Global South. We anticipate adding five- to six- additional members, who will help to establish and guide MediArXiv together with the existing members. In addition to governance, Steering Committee members commit to contribute to light moderation of submissions on a rotating basis.

Applications will be accepted through Friday, January 23, and successful applicants will be informed by January 30.

https://mediarxiv.com/steering-form/

More details about MediArXiv can be found at our information site:

Many thanks for considering MediArXiv service,

The MediArXiv Steering Committee

- Jeff Pooley, Associate Professor of Media & Communication, Muhlenberg College

- Jeroen Sondervan, open access expert & and co-founder of Open Access in Media Studies. Affiliated with Utrecht University

- Catherine Grant, Professor of Digital Media and Screen Studies, Birkbeck, University of London

- Jussi Parikka, Professor of Technological Culture & Aesthetics, University of Southampton

- Leah Lievrouw, Professor of Information Studies, UCLA

MediArXiv is a project initiated by Open Access in Media Studies:

https://oamediastudies.com/

As free, nonprofit, community-led digital archive, MediArXiv is fully committed to the Fair Open Access principles:

https://www.fairopenaccess.org/

Combination Acts

Memes and Everyday Fascism: A Triptych on the Collective Techno-Subconscious as Incubator of a Men’s Ideal

Historians tend to define fascism in terms of its historical manifestations, sometimes warning not to (over)use it in contemporary contexts. Yet, in the past few years, the world has seen the rise to power of figures like Trump, Duterte, Orban, and Bolsonaro, the stunning impact of the Alt-Right movement, and the Cambridge Analytica-scandal. Unsurprisingly, the slumbering interest in contemporary fascisms amongst cultural theorists and net critics has risen once again.

In November 2017, Sara-Lot van Uum and I interviewed Geert Lovink on the topic of meme fascism for the Fascism issue of student-run magazine Simulacrum, seeking to formulate a conceptual bridge from ‘historical fascism’ to ‘contemporary fascism’. We wondered: can we use the notion of fascism to analyze Trumpism and the Alt-Right movement? Does ‘fascism’ refer specific mode of societal organization, to a psychoanalytical mechanism?

In the year between Simulacrum’s interview and today, contemporary fascism has grown to be one of INC’s focus themes. For example, the two most recent INC Longforms are Pim van den Berg’s Execute Order 66: How Prequel Memes Became Indebted to Fascist Dictatorship and Roberto Simanowski’s Brave New Screens: Soma, FOMO, and Friendly Fascism After 1984. Furthermore, INC is working on the publication of BILWET: Fascisme, an anthology of Adilkno’s critical theory of ‘contemporary fascism’ from the 1970’s and 1980’s.

Today, I find myself working on this Bilwet/Adilkno publication. Wondering about the contemporary relevance of these texts from the 1970’s and 1980’s, I was reminded of the interview I conducted last year and decided to translate it.

First Panel – Contemporary Fascism: Method and Definition

Sara-Lot and Sepp: There is a lot of talk about fascism today, more than, say, five or ten years ago. Yet, this interest in fascism after the 1940s is not unique. Already in the late 1970s and throughout the ‘80s, you have extensively theorized ‘contemporary fascism’. Which methods of fascism analysis and what definitions of fascism did you have at the time?

Geert: The dominant discourse in the 1970s was characterized by a somewhat vulgar Marxist economic and political understanding that the major force behind the rise of Hitler and Mussolini was capital. This understanding held that the economic crisis in the 1930s was an effect of capitalism, but that the discontent caused by it found its political articulation in the fascist movements. Thus, already in the 1960s and 1970s, fascism was analyzed in predominantly historical terms.

Then, in the 1980s, after studying Political Science in Amsterdam, I went to Berlin and joined the writers’ collective Adilkno (Foundation for the Advancement of Illegal Knowledge). One of the first things we did in this collective was an attempt to reinvent the method of fascism analysis. Opposing the dominant historical mode of analysis, we drew on the psychoanalytical tradition of Freudo-Marxism. The latter discourse has its roots in Wilhelm Reich’s Fascism and Mass Psychology (1933), the first attempt to integrate Marxism and psychoanalysis. Freudo-Marxism became popular in the mid-1970’s, because it offered a foundation for a broader discourse, from the feminist socialist movements, in which the relationship between sexes is of crucial import, to academic exercises such as Cultural Studies. This large and important shift was most clearly articulated by Klaus Theweleit in Männerphantasien (1977), which brought together, for the first time, all the elements needed for a new type of analysis and a new definition: fascism as the over-identification of masculine ideals and their societal articulations.

This focus on the collective psychological structures latently present in all of us led to a problematization of the division of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ in the dominant discourse of fascism. Speaking of fascism in these terms was no longer a matter of projection onto the other, but a moment of collective self-analysis. Leading questions in such self-reflection were: what was it in fascism that people felt related to them? Why were fascist movements so popular? In Adilkno, we aimed to ask exactly these types of questions in the 1970s. Also, drawing on Foucault, we added to the lines of fascism and anti-fascism a line of non-fascism. By thoroughly analyzing the roots of the problem, we tried to formulate something close to a Hegelian synthesis rather than an anti-position.

A good example of how we used this new method and definition in Adilkno is Sexism-Fascism: A Reconstruction of a Men’s Ideal, a book which Basjan van Stam wrote after studying at the Free University in Amsterdam. In this book, a series of character traits are described as typically fascist: militaristic, explosive, hierarchic, though, superior, disciplined, performance-oriented, protective, full of expansion drift, sexist. In short: an extremely dominant masculine ideal. The type of characteristics we observe in Trump today.

You might ask why chose to analyze fascism in terms of sexism rather than racism, antisemitism, or homophobia. Again, I think this is because we are talking about a self-oriented analysis. There is a major problem in analyzing fascism in terms of racism or antisemitism: one ends up analyzing the other instead of oneself. This type of analysis supposes that we should learn to tolerate one another. In Adilkno, we were not satisfied in saying: if just we had properly liked Jews, nothing bad had happened. We wanted something more self-critical, contemporary, and fundamental. For instance, in Sexism-Fascism, Basjan analyzed the contemporary fascism implied in a series of Tintin albums.

Second Panel – The Emergence of Digital Culture: From Self-Psychoanalysis to New Media Theory

Sara-Lot and Sepp: It is interesting how you were working with the notion of contemporary fascism in the 1970s, but it may be even more interesting is the gap of the 1980s and 1990s. Before making the leap from the late 1970s to today’s situation, shall we consider what happened in this gap? It was a period which saw the emergence of postmodern thought and a decline in the popularity of psychoanalysis. Moreover, it is in this period that digital media and culture emerged. Can you explain your own trajectory within this gap/shift in contemporary fascist analysis and elaborate how you have come to focus on discourses like meme theory?

Geert: There was a very clear shift in the 1980s and 1990s from classic Freudianism, the clinical picture, and the ideas of analysis and therapy, to a much broader cultural analysis – paving the way for theoreticians such as Deleuze and Guattari, Baudrillard, and many others. I see this shift as a reorientation of the fundamental terminology in psychoanalysis. For me, this crisis in psychoanalysis and the subsequent postmodern reorientation resulted in a focus on new media theory.

I should note here that I did not enter new media as an outsider, but as an activist. We, digital activists, strongly believed that we could re-appropriate the top-down propaganda discourse of power by democratizing media. Actually, I still think that. Don’t misunderstand me: I see that we live in the era of Facebook and Google. Decentral digital activists have lost big time. Still, I keep believing that decentral networks can undermine all power relations (in Foucault’s sense) on the long run.

When I turned to media theory as means of activism, I found notion of the meme to be a central one. This is a notion derived from Richard Dawkins’s book The Selfish Gene (1976). Dawkins theorized the meme as a condensation of culture in the shape of a symbol that moves of its own accord through (digital) networks. This concept, the existence of such symbols, implies that ideology is not constructed solely by the big institutions. The meme is the neoliberal antipode of the ideological state apparatus (in Althusser’s sense). In the meme, an ideology is summarized in the condensed shape of a crystal. The power of such a symbol is that it brings together elements of identity and desire that speak to a lot of people.

New media theory, then, started studying this meme-crystal, but it was certainly not the first approach to analyze the power of the compressed image. We can see earlier attempts in visual culture, iconography, and – here we come full-circle – psychoanalysis. Even though it was a good tool, the problem with psychoanalysis has always been that it unconsciously stuck to top-down logic. Psychoanalysis always studies how the individual was appelated by power. In meme culture, the functions are reversed. Here, the central user is the user/blogger, who autonomously and decentrally works with the elements of desire and identity.

For this reason, we see an interesting relation between political views, ideological structures, and the emergence of memes. We can observe elements of propaganda in memes, but memes are never propaganda proper. Why? Because the primary subject of the meme is the very psychological constellation of the nerd, which means that memes are ever ironic. At the same time, exactly because of this self-referential quality, memes have the potential to mobilize discomfort, even when the individuals who create them have no clue by which political agendas these memes can later, in another constellation, be appropriated. This is dangerous. We cannot afford to be naïve about the danger of memes. There is a real possibility of political mobilization through memes. It is clear that old-fashioned populist politicians, such as Geert Wilders, do not appeal to younger generations at all. Memes, on the contrary, appeal very strongly to a broad, diffuse, and young public.

Third Panel – Meme-Fascism: Reading Escalated Innocence

Sara-Lot and Sepp: So, the activist potentials of decentralized networks brought to fore new media theory. However, the same decentralized networks resulted in the impossibility of psychoanalytical reading of the crowd in the digital age and thereby multiplied the task of new media theory: not only did it have to replace the activist function of psychoanalysis, but also the explanatory one. How do you see this task today? What can media theory say about meme-fascism, building on psychoanalysis after the failure of psychoanalysis?

Geert: If we were to attempt any sort of psychoanalytical or explanatory reading of meme culture, a directly political reading would be doomed to fail. Take, for example, cat images. These images contain a type of escalated innocence. The fact that millions of people spend millions of hours staring at innocent cats on their monitors implies a huge amount of poorly masked discomfort in everyday life. We could, of course, make some kind of quantitative analysis, we could map and visualize digital communication. But I think the real work starts only when we analyze compressed symbols and their separate parts using visual and psychoanalytical methods. The problem is that it is extremely hard to trace the narrative element necessary to turn this implication into substantial psychoanalytical theory. Digital communication is so fast, that the narrative element is immediately undermined and negated by the massive amounts of new information constantly pouring in.

For this reason, one could argue for a meme-analysis beyond psychoanalysis. However, this is exactly where Deleuzian strategy fails. Deleuzians are stuck exclaiming: ‘It’s a marvelous production! Ah! Production! Great! Wonderful!’ They can’t seem to proceed past this point.

So, however skeptical I am about the contemporary potential of psychoanalysis, I think that we somehow need the notion of contemporary fascism in explaining why memes are so popular, and why a very diffuse group of young men, nerds, is capable of making real political impact. Today’s Left, in being academically and politically correct, is incapable of communicating with these nerds.

Of course, we should give a lot of attention to the rise of the new Right. Yet, if you would ask me, looking at the specific examples of meme-fascism we see today, if meme culture is directly dangerous, I would say ‘no’. For instance, looking at the Alt-Right movement, we can clearly see a men’s ideal. But I think that this is a highly defensive and reactionary movement. If they do not rise to power now, they will soon cease to be visible forever. Moreover, I think that there are many possibilities of blowing up toxic meme culture from the inside, and to develop subversive strands of meme culture. We can create a language to create new majorities and to co-create new images that doappeal to people (this was already propagated in the 1930s within movements striving for a popular front). This is our challenge today. It is clear that artists and designers have a major task, but so do back-end developers, who determine the architecture of new technologies.

Speaking about these developers, I should emphasize that Google, Facebook, and other tech companies are extremely ambivalent in the matter we are discussing. On the one hand, they facilitate the phenomenon of meme-fascism, but, on the other hand, they are aligned to the global, liberal elites that do not identify with right-wing populist movements whatsoever. This means that Sillicon Valley should be put on the spot. So far, they have always said: ‘We only create the technical infrastructure, we shape the collective techno-subconscious, but we do not define what is articulated there.’ As the Cambridge Analytics scandal has shown, this position is untenable.

This brings us to the not-so-disciplined interdiscipline of media archeology. Because of its focus on materiality, media archeology is extremely important when looking at memes. It allows for the analysis of internal workings of the smartphone, to see how the interfaces of applications interact with the backends of chips and network structures. Why is it so easy to swipe? Which unconscious structures are called upon when we start ‘liking’? To the extent that it is materialistic, media archeology brings psychoanalysis back into the picture in a well-grounded manner.

So, how can Adilkno’s conception of contemporary fascism inform this material analysis of today’s digital infrastructures? I would say that the most important issue is today’s cynicism or nihilism. With its political correctness, the Left does not address but simply denies the broadly present contemporary nihilism. There is nothing more dangerous than this denial! Nihilism is not exactly racism, or antisemitism, but it does provide a fertile ground for sentiments like that. We should go at length to ask ourselves: what is so appealing about this nihilism? When people see that there is no clear direction in their lives, that they are jobless or permanently work under precarious circumstances, the nihilist idealism of complete detachment is tempting. Moreover, since memes are a part of male-dominated nerd culture, meme-nihilism includes contemporary insecurities about what masculinity is today. Therefore, meme-nihilism incubates a new men’s ideal.

Good Data – Publication & Book Launch

INC is happy to announce that in January we will publish a new title in the Theory on Demand series: Good Data – Edited by Angela Daly, S. Kate Devitt and Monique Mann.

To celebrate this there will be a launch & drinks on 24 January 2019 – 17:00 @Spui25.

The editors Kate Devitt and Monique Mann, and DATACTIVE will discuss the book and open the discussion.

Good Data

In recent years, there has been an exponential increase in the collection and automated analysis of information by government and private actors. In response to the totalizing datafication of society, there has been a significant critique regarding ‘bad data’ practices. The book ‘Good Data’, that will be launched at this event, proposes a move from critique to imagining and articulating a more optimistic vision of the datafied future.

With the datafication of society and the introduction of new technologies such as artificial intelligence and automation, issues of data ethics and data justice are only to increase in importance. The book ‘Good Data’, edited by Angela Daly, S. Kate Devitt and Monique Mann, examines and proposes ‘good data’ practices, values and principles from an interdisciplinary, international perspective. From ideas of data sovereignty and justice, to manifestos for change and calls for activism, this edited collection opens a multifaceted conversation on the kinds of futures we want to see. The book presents concrete steps on how we can start realizing good data in practice, and move towards a fair and just digital economy and society.

Bio:

Angela Daly is a transnational and critical socio-legal scholar of the regulation of new technologies. She is currently based in the Chinese University of Hong Kong Faculty of Law and holds adjunct positions at Queensland University of Technology Faculty of Law (Australia) and the Tilburg Institute of Law, Technology and Society (Netherlands).

Kate Devitt is a philosopher and cognitive scientist working as a social and ethical robotics researcher for the Australian Defence Science and Technology Group. She is an Adjunct Fellow in the Co-Innovation Group, School of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering, University of Queensland. Her research includes: the ethics of data, barriers to the adoption of technologies, the trustworthiness of autonomous systems and philosophically designed tools for evidence-based, collective decision making.

Monique Mann is the Vice Chancellor’s Research Fellow in Technology and Regulation at the Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology. Dr Mann is advancing a program of socio- legal research on the intersecting topics of algorithmic justice, police technology, surveillance, and transnational online policing.