Last summer I signed three contracts, and Passing Strange was the first one. I hadn’t written anything in two years at that point, and I had no idea if I could, because I can’t sit for long periods of time. I can’t concentrate. So, I signed three contracts for books I didn’t know if I could do.

The other two?

The second one’s a collection of all the short fiction I’ve done in the last ten years, and it almost all done. And the other one’s a novel that’s due in a month.

How’s it going?

Not well. I have about three quarters done, and for three months I’ve been going, It’s three quarters done. I have plenty of time. And now I have 36 days. And I’ve written half a chapter in the last two and a half months. I may be screwed. In which case they have to move it up a year, cos they have a tight deadline. I’m gonna see. I mean, I wrote half a chapter two days ago. [laughs] I mean, I wasn’t sure about Passing Strange. I was like, well, I’ll get it done, but I don’t know if it’ll be any good. And it turned out ok.

Yeah, it turned out ok

The novel’s a kids’ book so it doesn’t have to be quite as good.

Ouch! It doesn’t have to be quite as … long?

Passing Strange is 39,000 words, this one has to be 52-ish. But, I mean, it doesn’t have to be as sophisticated. I’m hoping it’s as good. But I’m not holding my breath. At this point I will settle for finished.

Are you enjoying writing it?

No! I was loving Passing Strange. I was getting up in the morning, and I was all jazzed to do it. I wanna do this, and this, oh and this! This one, it just … it feels like hard work. And you know how it is when you’re supposed to be writing, you can’t do anything else, either?

It’ll be close. If it sucks then the editor gets to send it back to me and go, it sucks. I mean, it sucks in this place, and this place, and this place. I can probably fix it. It’s getting it down in any shape or form that I’m having trouble with. I hate writing. I actually hate writing. I love ending what I’ve written, but I hate drafting. I HATE it.

You’re one of those people?

Yes! I’d rather do anything else than draft. Once I’ve got a draft, I love the fiddly bits.

I like the middle part. Not necessarily the fine-tuning–although I do get a bit obsessive about it–but the process in the middle when you’re working with the structure and characters, but they’re on the page. You don’t have to create them.

Yes, I love that part. I just hate the first third. I think I like the last third best because it’s just the little fiddly bits. But the middle, when you’ve got something to work with, and it’s like, oh ok, I need that. I need this piece here. And … but that beginning part is just like … [makes a face/shrugs]. I need to get something down on the page to work with. I used to be able to go pull a fourteen-hour day and come up from that and go: I’m not leaving this chair until I’ve written three chapters. My body won’t do that any more.

I can work for an hour at a time.

That’s not very long…

No, so it gets very frustrating when I’m really into it, and I have to set a timer to make myself get up. But at the point where I don’t want to be doing it, I’m like, how long has it been?

Twelve minutes.

- How many words is that?

112.

That’s not very many.

Have you tried other ways of getting it down? Recording your voice or

It doesn’t work. It takes me four times as long to correct the voice recognition software. And it’s not how I work. I write longhand and cross things out. I scribble and draw things in the margin. Nobody has come up with a program that is flexible enough for me. It’s too linear if you’re typing.

Eventually it gets to the point where the linearity controls the chaos, but that chaos needs to happen first.

Is that the painful part? The handwriting chaos part of the process?

Just getting started. Once I’m started it’s like I get there, and once I’ve got it written, then all I have to do is type it. That’s like the first round of editing and I’m fine with that. From then on, it’s just refining and refining and refining, but it’s getting started that I struggle with. It’s like inventing your own clay in order to make a vase. If I have clay, I can make a vase, but I don’t want to have to invent the fucking clay.

It hasn’t gotten any easier? You’ve been writing for a long time now …

I’ve been doing this twenty years and, nah, it doesn’t get easier.

Do you feel that’s a shame, that it doesn’t get any easier?

There were parts of Passing Strange–and actually I think there are parts of this book–that I sat down and wrote like 3000 words in a morning and most of them were keepers. When it works, it’s great!

It’s just with this particular book, it’s not like that. I just want it done.

I hope it writes itself for you.

You know, I keep hoping for that. I keep leaving all the material out on my desk, and it keeps not writing itself. I leave it paper. I leave it pens. I leave it everything it needs, and it’s still not writing itself.

You need the shoemaker’s elves to turn up …

The cat regularly knocks the pens onto the floor. Knocks various pieces of paper over someplace where I can’t find them. That’s less than useful.

We should talk about your beautiful new novella, Passing Strange.

Oh, yes, please. Tell me it’s beautiful!

In the middle of writing a terrible book, it’s nice to know that the one that I did manage to finish is good.

Do you not have any faith in your own work?

Since I finished writing Passing Strange in April, I’ve probably read it fifteen times, and I can’t find anything I would fix. It’s like petting an animal. You sort of feel like, Oh, I wanna read that part again. Oh that part’s really good.

So you do like the work, this work at least, as a reader?

I do. Yeah.

What do you like about it?

You tell me first. You’re the professor.

Well, to start with I like the title, which really sets up a sense of all kinds of strangeness, or queerness, and also evokes stories about passing, as a queer person. Not just in the usual sense, of passing as straight, but also passing through things, or being only passingly strange. At least to those who are strange in the same way you are.

And also, once you’ve read the work, that the speculative elements in the story are so light–so passing–that you could almost wonder if it is a speculative story at all. It’s a story that wears its genre identity lightly. A story that’s passing (maybe) as something other than what it is.

The story also recalled for me, the discussion around Karen Joy Fowler’s title ‘What I Didn’t See’ winning the Nebula short story award: how so much of the discussion around that was about whether the story was speculative fiction at all. Whether it should be ‘allowed’ to win. Whether it should be permitted in the ‘canon’. So this novella of yours, Passing Strange, has such an apt title, because in a sense the title could also be referring to the genre identity of the work: that it’s passing as strange fiction, but perhaps … well, perhaps it isn’t strange at all.

There’s the magic at the beginning and — oh, I don’t want to spoil it for you, Ellen, in case you want to read it again! — but there’s a glimpse of magic at the end, too.

Yeah. Did you read the novella that Andy Duncan and I wrote?

Wakulla Springs?

That got nominated for everything, and everyone was pissed off because it has no spec elements in it. Except that it’s Tarzan–who is a fantasy creature–and the creature from the black lagoon–who is a science fiction monster. But they were maybe just pissed of because there was no overtly spec element in the entire thing.

This time I thought, I’m actually gonna try. I’d never written anything where there actually is magic. I always find magic really hokey. Because everything else is so realistic. I thought, if I can make the magic realistic for myself, and actually find some sort of scientific explanation for why the magic is working, then I can believe in it.

So I did.

So there’s actual magic in Passing Strange.

Definitely, but it’s such a light touch, and everything else seems so rooted in the real. In detailed historical research … It’s a work of historical fiction as well, in one sense, do you think? A romantic, magical, alternative history of queer San Francisco?

I knew, from the beginning, that Mona’s was going to be in there. I mean, I spent a month reading Dashiell Hammett, from Black Mask, to capture what I wanted from the Mona’s chapters. I wanted it to be like gritty 1930s San Francisco, and then the World’s Fair [ed: Golden Gate International Exhibition of 1939/1940] is sort of magic on its own, because it’s all illusion. It’s so much larger than life. It’s not reality. Then the Chinatown stuff, I did the most research on. My god, I did like two months of research on that, because that was the one character that I figured if I got it wrong I was going to get shafted by cultural misappropriation and all of that stuff.

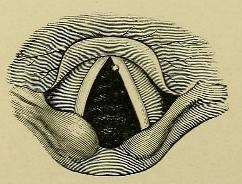

Photograph by Seymour Snear, taken at the 1939 San Francisco World’s Fair. From his book ‘San Francisco, 1939: An Intimate Photographic Portrait’ (pp.28-29).

So, do you mean particularly around creating the character of Helen?

I was trying to balance, from the beginning, all of the ways that San Francisco itself can be described as magic or an illusion, and all of the buzzwords that you use in fantasy, except using them in a non-fantastic context. And the ‘strange’ part, every lesbian pulp fiction paperback from the ’50s is titled something ‘Strange’–sometimes it’s ‘Queer’–but mostly it’s ‘Strange Sister’ or ‘Strange Lover’. The titles were just code for: this is gonna be queer. So I definitely wanted to have that in there.

Everyone except Franny is passing as something. Franny’s the only character who is pretty much just who she is. And everybody else is passing as something, or could do so.

Haskel doesn’t. Haskel doesn’t, really, but she could, because she’s …

Because she’s an artist?

Right. And there’s that conversation that she has with Helen, where Helen says, ‘Look, if you wanted to you could pass.’ And Haskel’s sort of like, ‘Yeah, but I don’t care.’ And Helen cannot pass for anything other than Chinese–

or Japanese

Well, she is Japanese. Or, I mean, culturally she’s not Japanese, ethnically she’s Japanese.

That was a really tricky part.

I wanted her not to consider herself Japanese except that she’s culturally, in those times, defined by what she looks like. Even though she’s like, ‘No, my family’s from Oregon. Get over it.’ Because she’s not culturally Japanese. And definitely not culturally Chinese.

I kept playing with that reveal of the fact that she’s not Chinese. I had it at the very end and then it was too dramatic. It’s like the beginning, where she goes, ‘this is my family.’

Everyone’s like, ‘But wait! Aren’t you …?’

‘No, and neither is anybody else at the show.’

I have diagrams of all the research … all of these diagrams trying to figure out, at 11:30 at night, how everybody is passing. And how everybody is related to each other. How they all know each other, without hitting you over the head with it.

So, from the beginning, was that a thing you wanted to explore, the various ways in which your characters are passing as someone other than who they appear to be?

It wasn’t at the beginning, but once I had the title. My working title was Love and Death in the Magic City, which is a terrible title.

There are probably about 11 or 12 other books called Passing Strange. There’s a Broadway show called Passing Strange. It’s not an unusual title, but once I landed on it … I mean, I’m crap with titles, and this is one of the first times it’s like Wow, that’s a really good title! I actually have a title. And then I tried to make the ‘Strange’ part fit. Like I said, it was paperback code, so I tried to take the ‘Passing’ and sort of weave it into every single person’s life in one way or another.

It’s the only reason that Polly does the trick where she appears older. Otherwise Polly’s kind of an outlier, and isn’t really passing as anything. But there’s another story that I wrote, which came out almost three years ago now, about Polly. Polly’s father is a stage musician. So, the story about Polly is another story that’s all about magic, but has nothing fantastic in it. [‘Hey, Presto!’ was collected in Jonathan Strahan, eds, Fearsome Magics]

It tickled me that three out of the six characters show up in other things I’ve written, and it’s like, Oh wait! Could that person be around in that year? Yes! Ok. That was fun.

Is that a common thing you’re doing– inter-connecting your stories? Or was it just a series of links you wanted to make in this particular story? To create a web.

I’ve got more up my sleeve, depending on what I end up writing. There are some stories that are going to be stand-alone because the time period is too strong, but now I feel like I want to interconnect everything that it can, so that it turns out that it’s just one giant world. Since I write mostly in ‘our’ world, sometimes slightly next door to our world, it’s just a matter of making the time-stream work. But yeah, at some point I would love to connect every story I’ve ever written. I’d like to have somebody show up as a minor character, and somebody else say, ‘Wait a minute, isn’t that …?’

That will make grad students happy.

Little Easter Egg hunts they can go on?

This is the first of those Easter Egg hunts. It was fun for me.

I wanted to ask you about the role of art-making and artworks in the novella. Haskel is an artist, and is making cover images for pulp 1930s magazines.

Yeah, her first is in ’33 and her last cover is in 1940. Her last cover in that world. I don’t know what she’ll do where she’s going.

Visual art is an important part of this book. I was thinking, too, about the presence of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

Frida never actually shows up because, unfortunately, Diego really was in San Francisco on that date, and Frida didn’t show up until the end of September, by which point the Fair had closed and they had to be gone. So, she just has to talk about Frida.

I love the fact that Haskel’s slept with Frida Kahlo.

That was a bit naughty!

Oh, it was fun. It was so much fun to write. When I started doing this 40 years ago, Haskel was an actress. She was from LA, and she’d come up, and she’d done all these things. Then I wanted Emily to be a performer, so I didn’t want Haskel to be another kind of performer, cause, neehhh. And Helen was also.

Once I bought Helen in, then I had two different night clubs, so I wanted Haskel to be doing something different. And at some point I have a note that says, maybe she’s a painter, maybe she’s a sculptor maybe. And I have a note somewhere that says, what if she’s an illustrator?

Then I was at Worldcon in Spokane last summer–and this was when I was just in the research and planning part of this, I actually hadn’t started writing–and I found a book on Margaret Brundage.

Actually, a friend of mine, over dinner, said, ‘Well, you know about Margaret Brundage.’

And I said, ‘No.’

Margaret Brundage was this woman who drew a lot of pulp covers, so I sort of modelled Haskel’s career–a little bit–on Margaret.

Most of the covers I describe are Margaret Brundage covers. Sometimes I throw in a few other details that aren’t in the Margaret Brundage covers, but the art is based more on Margaret Brundage than anybody else.

The rest of Haskel’s back story, I just sort of … you know, she just kept forming herself. And the fact that Franny does both art and other things? I wanted to get as much art and science in there as I could. I wanted to have them overlap and inform each other.

There’s a short story that Tor.com just put up called ‘Caligo Lane’. It’s a really, really short one, but it is an incredibly detailed description of exactly how Franny’s magic works. It came out like three years ago, and kind of disappeared without a trace. It’s set maybe three years after Passing Strange, but it is meticulous. It took my two years to write this 3000-word short story, because it’s exactly how the origami and the maps and the fog and everything work together.

So, if you want to find out about Franny and her magic, go and read this other story, which is written in a completely different style: it’s like a prose poem.

Anyway, in Passing Strange Franny’s got this art, and then Franny and Haskel can meet because of art. I didn’t want anybody to have a job as a truck driver: a stereotypical dyke job. Which is why Babs is a mathematician, because I wanted her to be some kind of scientist, and I thought, well, the math part is really kind of cool. So there’s the intersection of art and science, and science and magic, and art and performing, and being somebody in your art that is different to who you are in real life.

Is that how you understand yourself? Are you different in your art to how, or who, you are in real life?

My voice is completely different. When I’m performing and I’m telling a story, it’s a completely different voice than if I’m writing it down.

I’ve only done one prose version of something that I’ve actually done in front of an audience, and it was really weird. The syntax, everything, is completely different than my writing voice. My performing, storytelling, out-in-public voice is really different than my writing voice, which surprised me when I first started writing.

Somebody actually came up to me once and said, ‘It’s really funny that there’s a science fiction writer with your name.’

And I said, ‘It’s me.’

And they said, ‘No, it’s not funny.’

And I said, ‘No, look, it’s me.’

I don’t think I thought about that when I was working on this story. But yeah, I think that that’s in there. Emily is not who she is on stage. And Haskel is not, certainly not, what she draws. Helen is pretty much just doing it for the money.

That notion of these women in the Circle, they’re all in this place and time when being who they are is difficult, or problematic, for one reason or another. So they’re all living in the gaps of heteronormative cis-gendered white culture: a culture which, if they want to live safely in it, requires them to perform in some way. To be prepared to put on a show that they are someone other than themselves.

Except for Franny.

Exactly! Except for Franny. Why is Franny different? Why does she get out of that bind?

I don’t know. I kept trying to figure out how Franny is passing, or having to compromise herself, and I finally realised that Franny just is Franny.

I don’t think she actually cares. She’s not going to go out and flaunt things, but she dresses very oddly. She’s not particularly dressed like a man or a woman. Actually, she’s dressed almost Oriental. She wears tunics and pants.

I know who all of these people look like, because I’ve cast the movie in my head. I actually started with–a long, long, long, long, long time ago–I knew that Haskel was Lauren Bacall. I can send you the pictures I was working from.

Emily is a very young Katharine Hepburn.

And then there’s Helen. I found this story about aJapanese woman who had just won this swimming competition at the age of one hundred, and I thought, Ok then! I get Helen to be able to go into a basement by herself.

They’re all having to compromise in some way, but not as much as a lot of people. I like the contrast between Emily, who is dressed up in illegal way, and Big Jack, who is cross-dressing and probably would be trans now.

Emily isn’t, she just wears men’s clothing. I wanted there to be a very distinct difference between those two ways of being out and flaunting the heteronormativeness of it, but for very different reasons.

There are these locations in the novel–Haskel’s apartment, and Mona’s and the homes where the members of the Circle meet–where they can be themselves. Or play at being themselves, or dress up as other versions of themselves. That’s interesting to me, that in the novella these are safe spaces, but so many of them are consciously aware of being in dress-ups in those spaces as well. Of playing with their identities. At Mona’s especially.

Some of the people at Mona’s are. The pictures I’ve seen of Mona’s, mostly the people that people took pictures of were more cross-dressing than not, and were usually more butch than not. I mean, Mona’s really was so many things to so many people.

For some people, it was just a bar. And for some people it was the only place that they could be themselves. For people like Jack it was the only place that they could be employed, and for the tourists it was titillating and strange.

Strange. Some kind of human zoo.

Definitely. The tourists went there because it wasn’t normal.

For similar reasons that they go to Forbidden City, where Helen works; because it’s a place where they can have an encounter with the Other, with something exotic and ‘strange’. For titillation.

There was also a Negro nightclub, a Mexican night club. There was a gay man’s cross-dressing nightclub. Actually, it only closed down about five or six years ago, I think. There was a drag show forever.

There was a whole bunch of that kind of tourism. Most of it didn’t last through the war. It was fascinating stuff, but I decided I wasn’t going to be, like, Now I’ll have a Black character, and a Mexican character! No, I’m just going to have the two nightclub scenes play off each other.

And the World’s Fair is also going on, during the story, which is also a series of staging posts for experiencing the exotic in a strangely touristic and kitsch way. Some of them quite comical. I was really struck by the absurdity of it all. By the Estonian village where you could go and drink cocktails, and so on.

Me too! I have all these guidebooks from the Fair, and I’m trying to figure out where could they have gone to have a drink. So I look at the maps, and I think, Oh great! There’s a Chinese village, and there had been a Scottish village. (The Fair lasted two summers: closed down in winter and re-opened.) The first summer there was a Scottish village that also had a cocktail lounge, but it didn’t last to the second year. So at first I had the Scottish village and then it was like, oh fuck, it’s in ’39 and not in ’40. Well, what was there in ’40? And then I found the Estonians. I don’t even know what Estonian food is.

What would a reproduction of an Estonian village look like? It’s such an absurd, hyperreal environment. I think that’s what I’m getting at. Within San Francisco there are places like Mona’s and Forbidden City, and at the World’s Fair there are these equally constructed, contained, performative spaces, and they share this sense of being monkey’s masks. Like that Basho poem: Year after year / on the monkey’s face / the monkey’s mask. These are places that are offering a hyperreal version of reality to their audiences. But they’re also places people go to ‘be themselves’; to perform their ethnicity or sexuality for themselves and an insider audience of friends or fellow queers or Asians, but also for an audience.

They’re all forms of unreality. Forms of escapism. They’re all, in many levels of meaning of the word, fantasies.

Illusions. Performances. Some version of being Chinese, Queer, or Estonian, which are temporary and somewhat ephemeral. They can be packed up and taken away.

The World’s Fair will be. Well, they had built the island, and they were going to turn it into the San Francisco airport, but the war happened, and the Navy took it over. It’s been a Navy base ever since. There’s almost nothing left. I think there’s like one half a fountain somewhere. But it’s 40 acres.

It’s like Disneyland being wiped off the map. And turned into a Navy base.

I guess that’s what always happens with World’s Fairs: they’re erected, these enormous architectural event spaces, and then they’re dismantled or repurposed. They disappear underneath or back into the cities in which they arise.

Well, they’re never meant to be permanent. Although, the 1915 World’s Fair here, there’s still one building that’s left because they saved it. It’s now 102 years old, built out of plywood and plaster and chicken wire. It was not supposed to last for 100 years.

It was getting kind of fun uses in the ’70s, but yeah—they’re never meant to be permanent. They’re never meant to be real. I was hoping that I was playing off the distinction between the very real stuff that happens outside of Mona’s, and the slightly unreal stuff that happens inside Mona’s. Then the Fair is this whole thing of illusion, two miles out in the Bay. It really is like going to another world.

Definitely! When they get on the ferry to go out to Treasure Island, it just reads as fantastical. As unreal. I stopped then, and looked up whether ‘Treasure Island’ was a real place. I was both surprised and delighted to find out that it was real.

That was the most fun part. Absolutely everything was real, except for the characters and the tündérpor, which actually is Hungarian for ‘pixie dust’. I was playing with Google translate, and I was looking for how to say ‘pixie dust’ in 25 different languages, and most of them it was like, Well, that’s stupid. Nobody can pronounce that! And I got to tündérpor, and I went [giggle]. Ok. Sure.

You mentioned earlier that you started writing this novella 40 years ago. I’m presuming you haven’t worked on it constantly for that whole time.

I was 22, and in a new relationship, and my partner and I kept inventing all these characters, you know, the way you do when you’re young and in a relationship.

Wait a minute! You do? This is what you do when you’re young and in love: you invent characters together?

Yeah, you do. When you’re young. Oh, I don’t know. Maybe it’s just me. But you know, did you ever have a nickname for a lover, and they have a nickname for you? So you end up being Banana and Pookie, and sometimes Banana and Pookie take on lives of their own.

Emily Netherfield and Loretta Haskel came out of that.

I was just out of college. I was 22 going on 23. We’d moved to San Francisco from the mid-West. We had Emily Netherfield and Loretta Haskel, and I knew that Haskel was an actress, and my girlfriend was Haskel, and I was Netherfield. Except that Netherfield went by Spike.

I had this great description of this woman, standing at the end of this sleazy bar in trousers and a Fedora, just being a tough guy. So I wrote like four scenes. Emily Netherfield, she worked for a PR agency, and she went off to the Fair to take publicity photos, and met Haskel, who’s this actress.

That was one scene.

There’s this whole backstory, which happens in the ’70s, when this 22-year-old college student discovers that there’s this relative that she’s never known about.

That was one scene.

And then there’s a scene where Haskel’s husband is coming back, and Emily’s really upset, and Haskel goes, ‘Well, you know I’m not going to stay with you? I mean, really, I don’t want to live like Big Jack and Rusty. I want a house, and I want kids. But, you know, he’s off in the war and so for now I love both of you, but, you know, I’m bi.’

I can see from your face that that’s really depressing! I actually wanted this to have a happy ending.

Well, that story might be quite realistic, but it’s not very hopeful or romantic, which the novella is.

Yeah. There are a couple of things, like the line, But how can you eat garlic bread and fudge with the same mouth? That actually came from this break-up scene. They’re not even breaking up: he’s got a three-day pass, and he’s coming.

I kind of always knew he was gonna die. But all I’ve got is like four three-page scenes that I wrote in 1977, and I never did anything with them.

I kept them, though, and every time I changed computers I would bring the file over. The file was called ‘39Fair’, and I always wanted it to be set in the World’s Fair, because I just think that particular World’s Fair is just — I so wanna go there.

Me too! We can go together. If you fold the origami, I’ll come.

Ok. I can fold one origami piece, but I can’t draw a map for shit. So, it’s always been a trunk story, and when Jonathan [Strahan] said, last June I think, I’m acquiring novellas for Tor, do you want to write one? Like I said, I hadn’t written anything for two years. I had maybe three or years ago dug it out, gone and done a whole bunch of research, gone to the LBGT archives, found pictures of Mona’s, read some oral histories, had about another notebook full of research. I thought, Oh my God, I could write Haskel and Netherfield!

So I went back and read the stuff that I had written when I was 22, and went, Well, not that. No.

Why not?

It really wasn’t very good, but it was the germ of all of it. So it wasn’t like I spent 40 years writing the novella. I wrote the novella in about six months, but I had research from 40 years ago. I had old theatre programs from legitimate theatre. Your parents would go to the theatre and in the theatre program there was an ad for Mona’s. So I had all this stuff, and I thought, Oh, that would be fun.

I wouldn’t have written this when I was 22, for sure. I’m not sure if my 22-year-old self would like this as much as I do.

Why not?

Because the story that you end up telling is never the story that you have in your head. And I understand that now, and I really like this one. But I think, if she was travelling forward 40 years, there would be things she would be very pleased by, and things she would be appalled by. Can you imagine going 40 years into the future and meeting your 80-year-old self?

Please no.

Exactly. My 22-year-old self feels exactly the same way. It is an idea that I’ve had for my entire adult life, that I finally got the chance to bring to fruition. And it’s much, much, much better than I thought it would be.

I just got a four-star review from Romantic Times. I never thought that sentence would come out of my mouth. I’m slightly confused by it. But ok, it is a romance.

It’s very romantic. It’s very much about the romance between Haskel and Netherfield, but it’s also the romance of San Francisco. This city that’s dreaming itself up. The city as a fantasy.

My aunt and uncle lived out here when I was a kid, and we lived two thousand miles away. We came to visit them, I think, three times in my childhood. They live about 25 miles north of the city. Once a trip, we would come into the city, and we would go to Chinatown and buy cheap souvenirs. My mother wouldn’t let us eat in Chinatown, because you never knew what there was in that food, and there could be white slavers and opium dens, so we would go someplace and have a hamburger.

I grew up in a very flat, mid-Western, ordinary …

Columbus, Ohio. That was ordinary as it gets. And no romance. All the history was pioneers and the revolutionary war.

San Francisco just–. I fell in love with the city when I was eight. And I told my mom, ‘When I’m a grown up, I’m gonna move here.’

And she said, ‘That’s nice, dear.’

And when I got out of college, she asked me what I was going to do with my life. And I said, ‘Oh well, I’m moving to San Francisco.’

And she said, ‘Well, that’s sudden!’

And I said, ‘I told you, like, fourteen years ago.’

And she said, ‘Well, you were just a child.’

And it’s like: Columbus. San Francisco. Really, no brainer. When I first moved here, when I was 22, I fell in love with the quirky history and the fact that layers of the past were still visible. It was 1976 and ’77. So what was across the street from Mona’s was a serious punk club. And everything in current nightclub stuff was all punk and everything, but little pockets of stuff still existed from the ’20s and ’30s. That just fascinated me.

The overlapping of different times and places

Yeah, so it really is a love story to the city. When Jonathan was here last summer, I took him on a tour of everything in the book. This is where Mona’s used to be, and this is where Haskel’s studio used to be, and this is where this used to be. I mean, nothing is there any more. But we drove around and looked at the views, and it was like: Ok, this is where Franny lives and this is the view out there.

I’ll go on that tour.

I’ll take you on that tour. It was really fun. I mean, almost nothing is there, but if you’ve read the story then you can sort of squint and imagine what it was like then. And I’ve got, I dunno, 200 pictures of stuff from back then.

I ended up spending three days with Google maps. I found where I wanted them to be on the steps. And you can do this 3D view, where you can look out at Treasure Island, which is still there, it’s just a Navy base. And then I have all these photographs of Treasure Island at night, all lit up. And I was doing like the Vulcan Mind Meld with Google Maps and a Viewmaster reel, and these photographs, and old newsreels and all this stuff, and colour photos. And then trying to describe what happens when you mush them all together.

So the research was clearly really important for you, and was very comprehensive. It sounds as if it was research not so much about what happened, but about creating a sensory immersion experience, for you and then for your readers.

I love research. I love research so much more than writing.

I have a notebook that’s like that thick, that’s all research, and I would get a book from the library, or buy it on Amazon for a penny, and read through, and I didn’t know what the story was going to be, mostly, so during the research I would be reading something, and I would find a cool fact and write it down. Eventually it was like, Oh! Oh, those two things go together nicely.

It’s mostly a mainstream story, except that I have fudged the street where Franny lives. And Franny’s house is sort of made up. But I actually went and looked at blueprints of the building that Haskel’s studio is in, in order to get to the point where the one paragraph of description that I need, and sometimes that would be, like, 17 pieces of paper that I’m trying to boil down into one absolutely gorgeous paragraph that says everything you need to know about that neighbourhood.

Well, the building has been torn down, otherwise I would have gone to the building. It’s all real. I can show you pictures of just about everything. And I like that part of historical fiction. Taking this real place, and using it as kind of a stage set for your imaginary friends to walk around in.

This is why, you know, finding out that Diego Rivera actually was where he was, and had been at the Art Institute in 1931, it’s like. Ok, so Haskel can actually know him, and then that whole scene with Frida can happen. I wanted to hit the idea that Haskel is working through stuff in the painting. I wanted to hit that one more time from a slightly different angle. They really are horribly grotesque covers. They’re really misogynistic. They’re all these things, so I wanted to try to figure out a way to explain a horrible cover in a way that I don’t think anybody else has ever done.

But there is an appeal in those Brundage covers, those pulp images, for contemporary viewers. There’s a kind of kitsch appeal, perhaps. When I look at all those pulp covers, they evoke a different world. A different world, with a different aesthetic, and a wildly different sense of the fantastic.

Yeah. I mean, there were more than a thousand pulp titles at one point or another. And Weird Tales is obviously the most well-known of those.

The detective ones you got detectives, you got people shooting each other, you got guns, you got dames.

I wanted to do the Weird Tales ones partly because that was what Margaret Brundage actually drew for, partially because they really are misogynistic and racist and horrible. And I’m thinking, Oh my God, how could you paint that? I wanted to give Haskel a reason for painting it.

I love the paragraph where she says, ‘Eh, the monsters are easy. Those are just a writer’s nightmares. But the fear. Every time I paint fear, I get more of it out.’ So, the Frida Kahlo conversation: I just love the fact that she learns that from Frida Kahlo. That they’re sitting there going, Well, I’m in pain.

Yeah, but how do you get that into a painting?

Well, you do this. And you paint things like being in this horrible back brace and really unpleasant things that make the viewer turn away.

Besides which, Frida Kahlo. I mean …

I get really obsessive with research. It’s like, I knew that Frida Kahlo had four paintings exhibited in the art building. Nowhere online–I searched for days and days–could I find out which four paintings they were. And it didn’t really matter, because I could have just said there was a picture of a woman with very prominent eyebrows. But I found out. I actually bought the art catalogue on eBay, found out what the pictures were, and then looked up online to find them in colour and describe an actual painting that really was hanging there. Because I’m obsessive that way.

Why is that so important to you, particularly when you’re working in a genre that’s concerned, often, with what can be imagined, rather than what is real? You have permission, in this genre, to play with reality. To bend it.

Like I said, I find magic hokey. And I give myself permission to play, but I really like the playground to be solidly established.

Partially I’m that obsessive because if somebody goes and looks it up, and finds out that I’ve fudged the history part, they stop believing in the true bits. And if they don’t believe in enough of the true bits, they stop believing in the characters.

I’m not certain if the second part of that is true, but I do know that I’ve had people go, Well, this isn’t right, and they look it up, and it’s right. I think that they start trusting me with the facts, which means that they also stop remembering that the characters are fictional. Especially when you’re mixing real people and fake people.

But the Frida Kahlo one was just because I wanted to know what picture it was. Because I wanted to describe it. Because I needed the moustache part. I needed Emily to say, ‘I have a moustache.’ And Haskel to say, ‘No, you don’t.’ And she says, ‘I mean I own one.’ it sets everything up for later. Otherwise it’s like, Oh, by the way, I have a moustache. Which probably would have worked, but I liked the set up. I also like Haskel going, ‘No you don’t.’

I watched probably five Lauren Bacall movies, and five Katharine Hepburn movies, before I started writing dialogue for them, because I was trying to get the cadence of those two women on the page. So that even if you don’t know that in my head it’s those two women, they have different cadences when they talk.

I wanted to ask you about why you write queer science fiction, or fantasy?

My very first story is a story called Time Gypsy that’s set in 1957. It involves a gay bar bust. And again, it’s almost all completely true, except that the two characters are fictional. It starts with, apparently, not particularly believable time travel. Although I worked really hard to try to make the time travel plausible. The rest of it is just set in the past, so it’s not actually science fiction. It was my first story, and the review said something like, Well, this really isn’t science fiction except for this one little bit. Everything in it is really, really good.

And then mostly, well, there are characters I’ve written that I kind of know will either grow up to be queer, or are, but almost none of it is overtly queer. Except for my first two stories, because I wrote them for queer anthologies.

I’ve always known that Haskel and Netherfield are lovers, and it’s Mona’s, so I wasn’t going to straighten them out. I think it’s going to bring a completely new audience to my work. Not only is Romantic Times reviewing it, but I’m pretty sure that the Lambda people will review it. And so it’s getting out of, to some degree, the science fiction ghetto, and getting a much broader audience.

That’s surprising to hear: do you see the queer audience as being broader than the science fiction readership? Or the romantic readership, or the historical fiction readership? Are you suggesting that you see those genres as broader, less ‘ghettoised’ to use your own term, than science fiction?

It takes it out of the little science fiction pocket. And because the magic is reasonably slight, you can read it as a romance that’s sort of paranormal romance (although I hate that term).

You can read it as a queer book, that’s sort of queer fantasy ish.

You can read it as a science fiction book that’s queer.

I’m sure that I have a fairly big dyke following for some of my books. I mean, all of my stories have girls in them. Most of them are not overtly anything. I’ve got a story with a four-year-old. She’s nothing. She’s a kid. Actually, most of my stories don’t involve any kind of sexuality because they’re usually kids under 13. And the few that do, just have two women, and I don’t make a big deal of it. And nobody–no, just with one fantasy story I wrote–somebody objected to the fact that it was two women. Because it was pointless. They were like, There’s no point to that. I’m like, Welcome to life. I said, These are my neighbours: they’re heterosexual. With some things, it’s just like, yeah, these are two women.

I will have guys say, why do you always write about women? Why do you write about girls? And I’ll say, because I was one. And I write women because I am one, and because I think it’s really important that if you’re going to write an adventure story of any kind you–you know–I don’t want to have to pretend that I’m Tarzan. I want to actually write Shena, Queen of the Jungle.

Andy and I talked a lot, in Wakulla, about how we wanted to balance the people of colour, and the real people, and all of that. We made a very deliberate decision to make all of the protagonists Black. Although neither Andy or I are. It was a big risk, because if we’d got it wrong, we would have gotten creamed. What we got creamed about was that it wasn’t science fiction or fantasy. Nobody seemed to object to our cultural appropriation of people of colour, which I guess means we did it right.

So much of the stuff that I’ve read, that’s queer, is bad. And it’s like, it gets out there because it’s queer. But it’s ham-handed, and usually not well printed. You know what I’m talking about: small queer presses. So I actually wanted to write something really good that was also absolutely blatantly, you-don’t-have-to-even-squint all these people are queer. All of them. I’m not sure about Polly. I think Polly’s straight. But everybody else, they’re dykes, and they are not stereotypical dykes.

I will be interested in how it’s received. So far, I’ve only seen two reviews. I will be interested to see what genre reviewers think of it. Be interested to see what any reviewers think of it.

Have the reviews you have seen not been from genre reviewers?

The Romantic Times? Genre, but not my genre. Publisher’s Weekly gave it a starred review, which is a wonderful and excellent thing. But I haven’t seen any reviews inside genre. It’s not out until four weeks from tomorrow. It’s supposed to come out.

It’s still in the closet.

It is.

Are you nervous about it being released?

Not as much as I was a while ago. Because, yeah, I want everybody in the world to like it and buy it, and nobody say anything bad about it all.

I’m happy with it. Everybody who has read it so far has liked it. And the first two reviews, which are way out of my wheelhouse, liked it. And after Wakulla, if people are going, Not enough science fiction; not enough magic! Well, there’s magic.

Look, it’s magic.

I think that stuff about policing the boundaries of the various genre fields is interesting. Being so invested in, and arguing over, what’s allowed in, and on what terms, is such a big part of social debate around speculative fiction lately. Even the whole Sad Puppies thing is about a different kind of policing of what should and should not be permitted or celebrated. Do you think that there’s more of that going on now than there used to be? More anxiety and debate around these issues?

Wakulla really didn’t have any fantastic element. It was a conversation with the fantastic. Very much like what Brian Attebery was talking about in his speech [Professor Brian Attebery’s keynote at the 2016 James Tiptree, Jr. Symposium’s Celebration of Ursula K. Le Guin]. And it’s a line that Andy and I would have liked to have had, two years ago: well, it’s a conversation about genre.

It got nominated for a Nebula, a World Fantasy Award, a Locus Award, and I think something else. When it got nominated for the Hugo, fan boys went ape shit about the fact that it had denigrated the Hugo, by being nominated. Anything else that had been nominated for a Hugo was now a lesser thing because this thing could get up. And everybody said, you know, It’s the best written work on the ballot. But the fan boys said it shouldn’t qualify because It’s not fair. It breaks the law.

But what is this law? Who laid down a law about what is, or isn’t, science fiction or fantasy? Isn’t that just an onging conversation we’re all having?

The law is that it actually has to be science fiction or fantasy. And it isn’t. It’s an entirely mainstream book about the filming of a Tarzan movie, so one of the most canonical fantasy figures of the early twentieth century. And the filming of The Creature From the Black Lagoon, one of the most canonical science fiction movies of the last half of the twentieth century. But its mainstream: nothing magic happens.

After that it’s like, bring it on. And Passing Strange really does have magic.

The only thing I’m worried about is that it’s coming out the very beginning of the year, and by the end of the year nobody will remember it exists.

That’s tough, in terms of award nominations and stuff. Is that what you mean?

It was supposed to come out in September. It was due the first of May, and supposed to come in September, and by the time I had finished it they had done a couple dozen novellas and realised, oh, it takes actually a lot longer to do one of these in print than it does just to put one up on the website, so it’s not coming out until January.

It’s a very memorable work; I’m sure it will be fine.

I hope so. Because they don’t do novellas in December, because nothing happens in December.

And they couldn’t squeeze it in in November. We will see. It’s coming out the same week as–let me see–it’s the week after Nnedi Okorafor’s sequel to Binti, and the week before a new Caitlín Kiernan novella, and two weeks after a new Seanan McGuire novella.

So, there will be lots of wonderful things for people to read during that month.

Yes. I’m hoping it holds up. My elevator speech is: it’s queer, noir, pulp, magic, magic realism, historical fiction, and screwball comedy. A little bit of screwball comedy.

My favourite line in the entire story, I think, is when Helen says, ‘I have fish heads.’

And Emily says, ‘Most people just get the milk delivered.’

I don’t know why, but I absolutely love that. I want to see that one filmed. Because I can’t do Katharine Hepburn’s drawl, but just that kind of [in a KH impersonation voice], Most people only get the milk delivered.

That was pretty close.

Except that that’s older Katharine Hepburn. But yeah. So, a little bit of screwball comedy.

This is not necessarily a great segue, but I wanted to ask you about your love for writing short form work. You’ve written a lot of short stories, novellas, novelettes. You haven’t written any big fat novels. Unless they’re in your bottom drawer somewhere. What is it about the short forms that appeals to you?

I wrote an essay on this at Tor.com. Basically, because I love the details. And I also love the fact that it has a definite beginning and an end, and you get to sort of make up what happens next. In a novel not so much. Passing Strange definitely has a story arc. It has much more plot than almost anything else I’ve ever done. On the other hand, I’ve had people go, So the next one’s going to be, like, what happens to them when they go into the painting.

Why would I do that? You get to make up what happens to them when they go into the painting. That’s the fun of it. You get to make up whether you actually believe they go into the painting.

I love the ambiguity of the ending of short fiction, because if it’s not ambiguous in short fiction, it’s usually trite. The longer you get, I think, the less ambiguous the ending needs to be, because then it’s unsatisfying. Like you’ve spent 400 pages, and the ending goes, There was a knock at the door, and people turn the page and go, what the fuck?

But in a 2000 word short story, or a 3000 word short story, or even a 10,000 word short story, it’s just this little still life. My first short story collection, the afterword says, many of my stories appear to have happy endings. So I want you to go, Oh ok. And then wake up in the middle of the night and go, Wait a minute! What about…? But…

And the people who want me to explain exactly what happens? It’s like, no. No, that would make it trite and boring and ordinary.

The weird thing is that when I was in school, I hated those stories.

Trite stories?

No, the ones that had ambiguous endings. Where you went, like, I don’t know what just happened! What happens to the dog?!

I start out with stick figure characters, like heroic space captain, and then think, Ok, what if he’s a cowardly space captain. What if she’s a he. What if he’s a dwarf. And somewhere in there, in just playing with the reversal of expectations, I actually find a human character and go on with it. But mostly with the stories, the ending is usually really trite. Or the plot is really trite. And then I have to fix it. Because that’s a bad story.

For me it’s a bad story. For me, it feels really trite.

I grew up wanting to write Twilight Zone stories. You know. It’s a cookbook!

Do you mean in the sense of those classic ‘twist in the tale’, jar-of tang style endings?

Yeah! Written a couple of them. And they’re really not my best work. They didn’t get reviewed terribly well.

Part of it is, I think, I love the language so much. I spend six months on a story. So, you know, if I’m tossing one out in an afternoon, that’s fine. It’s trite. It’s hackneyed. It’s sold! I’m onto the next one.

But I write them one at a time, mostly. I spend a whole lot of time with them, with every single comma and every single word, so by the time I get to my trite ending, it feels really trite. It’s like ewww. That’s where I thought it was going, but … ewww. It seems predictable. What I love in a short story is when I get to the end, and the ending seems inevitable but not predictable. Like, Oh, well of course that’s what happens. But you don’t know from the very beginning. It’s like …

It’s not pat.

Every once in a while I think, I’m just gonna knock this sucker out, and I just can’t do it.

Have you gotten slower since your injury?

Sometimes. Because sometimes I’m in too much pain to concentrate, and I can’t find a comfortable position to sit in. And I can’t sit for very long. I can write for an hour and that may have been a four-hour, just everything dumping out session in the past, but I can’t do it any more. So I don’t know that the actual writing is slower, but the process is certainly slower. Because I have to break it up into chunks.

Do you think it’s changed your writing?

It’s interesting that Frida Kahlo shows up in your story, with her back pain, and her idea about using the art to both express and escape pain. That accident certainly changed both her process, and the art she was producing.

That was a kind of deliberate choice, one day when it’s like, Fuck, I can’t do this. And because I was researching, I thought, Well, what would Frida Kahlo do? It’s like Oh, fuck you. Frida Kahlo would be on morphine and painting weird things.

I think it’s definitely changed how I feel about writing. It’s changed the process. I don’t know if it’s changed the writing.

I like to think that whatever my most recent thing is, is probably the best thing I’ve done. And I think this is the best thing I’ve done. I don’t think it’s qualitatively better, better, better than the last thing about which I thought that, but I really wasn’t sure when I signed the contract, and cashed the cheque, whether I could get to that level again. Whether or not I was going to be writing Klages-lite just because I couldn’t find the focus. So I’m really, really relieved that I still seem to be able to write.

You’re a big part of the genre community in the states, in particular, so I wanted to ask you where you think we’re headed. If you could draw a map, and fold a piece of origami so that we could travel through time and space to the genre’s future, what do you think you’d discover. What would you hope to discover?

I don’t know where the United States is headed. I hope that the Puppies will not take over science fiction and ruin the Hugos and keep shading everybody else’s playground. But I don’t know. Because they’re not playing by the same rules. And I have even bigger fears about what Trump’s gonna do, because he’s really not playing by the same rules. So, do I hope that the forces of good and right will prevail? Yeah. Do I have more confidence in that coming up on this new year than I did last year? No, I don’t. No.

The thing with the Internet is that it makes it possible for anybody to publish anything. It’s not like publishers can say, Well, we’re not going to publish your horrible, militaristic, right-wing crap. Because they don’t need a publisher. They don’t need an editor.

I think that there’s still going to be quality stuff. I mean, the Tor novella line, just as an example, is putting out really amazingly good stuff. And novellas have traditionally been rare. Some years there are four or five published, because if you’re in a print magazine, they take up two thirds of the magazine. So, they really better be good. And they’re long. You know, you write another 20 or 30 thousand words and you’ve got a novel. In my case, you write another 900 words and you’ve got, technically, a novel. So, there’s really good stuff coming out. The people that I know are that audience.

Science fiction is a whole bunch of Venn diagrams. There some people that love space opera–doesn’t really do it for me–there are people that love the militaristic science fiction and love Bujold. I’ve read one of them, and it was really good, but it just wasn’t my cup of tea. It’s sort of like the difference between someone who orders broccoli and somebody who orders mac’n’cheese. They’re both perfectly lovely side dishes.

I would like to be very hopeful that really good writing is going to prevail. The Tiptree still exists, so it’s pulling stuff out that otherwise nobody would know about. Like your book. If I hadn’t gone to Clarion with you, I wouldn’t have known about your book. I wouldn’t have sent it to the jury, and blah, blah, blah. There’s a whole lot of inter-connectedness, but like across the rest of the United States there’s also big divisions and schisms. I think they may be bigger than they ever were. On the other hand, 40 or 50 years ago there weren’t schisms because it was all white guys writing science fiction about martians and rocket ships and stuff. As the field gets more and more diverse, everybody in it gets more and more diverse. So I think there’s more division now because there are more pieces to the puzzle.

More voices?

There are more voices, and that many voices are almost never gonna make a choir without a rehearsal. If everybody decides to get together I’m sure we can blend our voices, and I think that would be really cool. But you have to get everybody to agree to play nice together, and I don’t necessarily see that happening any time soon.

You almost have to start before that: you have to agree on what we’re getting together for. My sense is that we’re becoming more and more aware that there’s enormous disagreement about what science fiction, or speculative fiction more broadly, is, or what it should or can do. We can’t even agree on that.

I don’t really see the need for it.

Totally, we don’t have to agree, as long as we can have productive disagreement. Disagreement that is comfortable with a lack of laws about what genre is, or what it might be going forward. The Puppies stuff, for me, seems to be problematic because it wants to insist on a singular, narrow definition of what’s acceptable. And reject anybody else’s idea of what’s good, or acceptable.

Every panel I’ve ever been on that even touched on this, somebody says, well, what is the difference between science fiction and fantasy? Everyone throws up their hands, going, What do you think it is?

It’s in the eye of the beholder. And it doesn’t matter. If you like the book, and you have try to squish it into a label, it means you’re doing the wrong thing with the book. Like the book: stop trying to label it.

The Green Glass Sea. I had a friend–it had just come out–I was sitting at my dining room table. A friend picked it up, started reading, and said, God, this is really good. I wanna get a copy of this. I really like the fact that the print’s bigger than in most books. You know, you get to be our age, and that’s a bonus. And I went, Well, that’s because it was published as a children’s book. And he went, Oh, well I don’t read those. And put it down. So, I’ve had people pick up a book, read part of it, go, this sounds really interesting, turn it over, see the word science fiction and go, I don’t read that crap. But, until you read the label, you were loving it. So I would rather just see us do away with labels. And just have a bookstore where everything’s alphabetised.

At the same time, there are threads within fiction–do you think–sets of images, tropes, themes, ideas, that you’re attracted to. A conversation, if you like, that you’ve been listening in to for a while and want to continue to listen in to. Or even become part of. I look at my bookshelves, for example, and there are lots of stories about women, and about queer people. Lots of science and history, nature writing and fairy tales.

I look at my bookshelves, and I see lots of mysteries.

It would be shame, I think, to do away with any way of grouping works of fiction. Any way of navigating the forest. Of finding the books that will resonate with you.

Things like, you walk into a bookstore, and you see a shelf that says ‘Staff Picks’. There’s like twelve books, and they’re not usually by genre. Depending on the book store.

On the other hand, it might be like going into an Indian restaurant and all they have is Japanese food and you’re going–or there’s Chinese food and burgers–and you’re going, but wait, I want Indian food. And they say, well, that’s very narrow of you.

There’s a restaurant where I live, actually, that’s breaking down ethnic and genre boundaries. It’s a Mexican restaurant, and on the menu there are only burgers, or fish and chips.

Do they have guacamole on them, or something?

No. But the restaurant is all decorated with sombreros and donkeys wearing Mexican cloths and carrying loads of corn.

It’s a bit like the history of gay bars, anywhere. It’s just a bar. It becomes a gay bar when gay people go there. And when gay people stop going there, for whatever reason, it gets sold to its new owners. The bar gets busted, depending on what year it is. Some loud club goes up next door. And the next time you go by there it’s a completely different club. The building hasn’t changed, but it’s not a gay bar any more.

I think genre wars aren’t necessary. It is a nice way to go: tonight I want Mexican food (and then you realise, Oh, don’t go there because they only have fish and chips). But, on the other hand, fighting about what is and isn’t Mexican food …

In Mexico, you can get a grilled cheese sandwich. It is, by definition, Mexican food because it’s in Mexico. I think the people that are using genre to be divisive are not helping anybody. And the people who are using genre to be more inclusive and diverse are spreading things to a larger audience, including more diverse voices. You know: a choir with just sopranos is kinda boring.

Welcome to Voices Carry. . . a forum meditating on the material production of human voices the social, historical, and political material freighting our voices in various contexts. What are voices? Where do they come from and how are their expressions carried? What information can voices carry? Why, how, and to what end? In today’s post, Alexis Deighton MacIntyre explores society’s interpretations of voicing, sounding and listening. Inspired by Christine Sun Kim and Evelyn Glennie, Alexis advocates for understanding voicing as movement and rhythm instead of strictly articulated sound. – SO! Intern Kaitlyn Liu

Welcome to Voices Carry. . . a forum meditating on the material production of human voices the social, historical, and political material freighting our voices in various contexts. What are voices? Where do they come from and how are their expressions carried? What information can voices carry? Why, how, and to what end? In today’s post, Alexis Deighton MacIntyre explores society’s interpretations of voicing, sounding and listening. Inspired by Christine Sun Kim and Evelyn Glennie, Alexis advocates for understanding voicing as movement and rhythm instead of strictly articulated sound. – SO! Intern Kaitlyn Liu

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig: