I see them in the streets and in the subway, at dollar stores, hospital rooms, and parties. I see them silently dangling from electrical cables and tethered to branches of trees. Balloons are ghost-like entities floating through the cracks of places and memories. They are part of our rituals of loss, celebration and apology. Yet, they are also part of larger systems, weather sciences, warfare and surveillance technologies, colonialist forces and the casual UFO conspiracy theory. For a child, the ephemeral life of the balloon contrasts with the joy of its bright colors and squeaky sounds. Psychologists encourage the use of the balloon as an analogy for death, while astronomers use it as a representation for the cosmological inflation of the universe. In between metaphors of beginning and end, the balloon enables dialogues about air, breath, levity, and vibration.

The philosopher Luce Irigaray argues that Western thought has forgotten air despite being founded on it. “Air does not show itself. As such, it escapes appearing as (a) being. It allows itself to be forgotten,” writes Irigaray. Air is confused with absence because it “never takes place in the mode of an ‘entry into presence.'” Gaston Bachelard, in Air and Dreams, calls for a philosophy of poetic imagination that grows out of air’s movement and fluidity. For Bachelard, an aerial imagination brings forth a sense of the sonorous, of transparency and mobility. In this article, I propose exploring the balloon as a sonic device that turns our attention to the element of air and opens space for musical practices outside classical traditions. Here, the balloon is defined broadly as an envelope for air, breath, and lighter-than-air gases, including toy balloons, weather balloons, hydrogen and hot-air balloons.

PLACE /

Vertical Dimension: Early Experiments in Ballooning, Sounding, and Silence

On September 1939, Jean-Paul Sartre was assigned to serve the French military in a meteorological station in Alsace behind the frontline. His duties consisted of launching weather balloons, monitoring them every two hours and radioing the meteorological observations to another station. Faced with the dread of war and an immediate geography that he compared to a “madmen’s delusion,” Sartre took his gaze upwards to the weather balloon and its surrounding atmosphere to find refuge. In Notebooks from a Phony War, Sartre describes the sky as “my vertical dimension, a vertical prolongation of myself, and also abode beyond my reach.” The balloon becomes a vessel for an affective relationship with the atmosphere that is mediated by the sounding of meteorological data. While gazing into the upper air, Sartre experiences a tension between the withdrawn”frozen blackness” of the atmosphere and the pull for feelings of oneness with it.

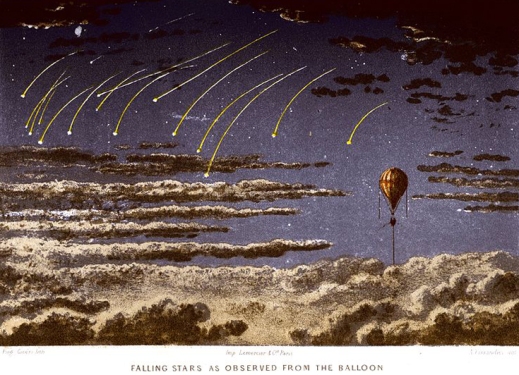

Falling Stars as Observed From the Balloon, Travels in Air by James Glaisher, 1871

The first balloonists to explore the atmosphere felt similar sensations of belonging by moving along masses of air, and at the same time, experiencing a deep sense of otherworldliness. Despite the dangerous enterprise, early balloon travelers repeatedly recounted expressions of the sublime associated with the acoustic qualities of the upper air. Late 18th and 19th-century balloon literature features countless textual soundscapes of balloon ascents that reveal how the experience of sound and silence helped frame early narratives of “being in air/being one with air.”

Ballooning developed in France and England among the emergent noise of industrialized urban life. The balloon prospect, as the author Jesse Taylor put it, spoke to “the Victorian fantasy of rising above the obscurity of urban experience.” Floating over the city, the English aeronaut Henry Coxwell describes hearing “the roar of London as one unceasing rich and deep sound.” In the same spirit, the balloonist James Glaisher compares the “deep sound of London” to the “roar of the sea,” whose “murmuring noise” is heard at great elevations. Ascending to higher altitudes, Coxwell hears the sounds from the earth become “fainter and fainter, until we were lost in the clouds when a solemn silence reigned.”

L’exploration de l’air, In Histoire des ballons et des aÇronauts cÇläbres, 1887

The balloon not only allowed access to a panoramic and surveilling gaze in the midst of boundless space but also a privileged access to a place of quietude and silence. In the memoir Aeronautica (1838), Thomas Monck Mason speaks to this point when he writes, “no human sound vibrated (…) a universal Silence reigned! An empyrean Calm! Unknown to Mortals upon ‘Earth.” According to Mason, when the balloonist goes “undisturbed by interferences of ordinary impressions,” like the sounds from terrestrial life, “his mind more readily admits the influence of those sublime ideas of extension and space.”

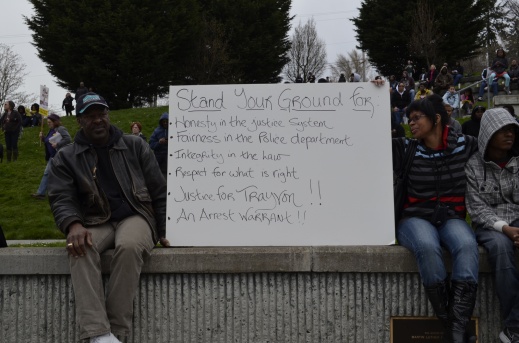

The experience of silence in the upper air brought forward in the Victorian white elite the longing for freedom, individuality, and assertion of social identity. Balloon flights provided a form of escapism from the confines of city walls reverberating with the aural manifestations of the Other. In Victorian Soundscapes, John Picker examines the struggles of London’s upper class of creatives (academics, doctors, artists and clergy) in finding spaces of silence away from the bustling noise of the urban environment. During the mid-19th century, the influx of immigration and the rise of commercial trade and street musicians altered the soundscape of the city. As Picker documents, the English elites rallied against this emergent aurality through racialized listening made evident by the use of sonic descriptors like invasion and containment that underlined anxieties related to the dilution of national identity, culture, class division and territory. For the elite, to physically ascend above the noise of the Other into the silent regions of the atmosphere via balloon, an instrument that dramatizes scientific prowess, validated an auditory construction of whiteness organized around ideals of order, rationality and harmony.

Circular View From the Balloon in Airopaidia by Thomas Baldwin, 1786

The descriptions of balloon ascents featured in James Glaisher’s book Travels in the Air (1871) are a vivid manifestation of these ideals. Experiences of floating at high altitudes were often met with poetic reports on the “sublime harmony of colors, light and silence,” the “perfect stillness,” and the “absolute silence” reigning “supreme in all its sad majesty.” The nineteenth century’s constructs of “harmony” and “quietude,” argues Jennifer Stoever, were markers of whiteness used to segregate and de-humanize those who embodied an alternative way of sounding. The Victorian balloon memoir echoes the construction of this sonic identity rooted in the white privilege of being lighter-than-air and claiming atmospheric silence. The balloonist Camille Flammarion, upon hearing “various noises” from the “dark earth” below, questions what prompts “the listening ear” to be sensitive to difference. “Is it the universal silence which causes our ears to be more attentive?” asks the aeronaut.

Balloon Prospect, In Airopaidia, Thomas Baldwin, 1786

Balloonist’s encounters with silence in the upper air and the sigh of “boundless planes” and “infinite expanse of sky” were accompanied by feelings of safeness and overwhelming serenity. Elaine Freedgood argues that the balloon with its silk folds and wicker baskets were a perfect container for states of regression and the suspension of the boundaries of the self into an oceanic feeling of at-oneness with the atmosphere. According to the author, the self and sublime become momentarily entangled originating a sense of heroic masculinity, power, and the rehearse of imperial and colonial ventures. This emotional state justified an unprecedented mobility and the sense of losing oneself to the whims of the wind with no preoccupations of where to land. However, in an image that contrasts the privileges of mobility, Frederick Douglass uses the metaphor of the balloon as the terrifying anxiety of uncertain landing – either in freedom or slavery. The novel Washington Black (2018) by Esi Edugyan, deals with similar issues by fictionalizing the balloon ascent and traveling of a young slave, whose hearing is tuned to the “ghostly sound“ of human suffering coming from beneath.

By late 1780s, thousands of people witnessed the European wave of balloon flights, but only a small fraction had access to them. Mi Gyung Kim, author of The Imagined Empire, draws attention to the silence imposed on the figure of the “balloon spectator” whose dissident voices were erased by the dominant colonial narrative of aerial empire. Mostly, the balloon spectator is featured in Victorian texts within a soundscape of affects characterized by “vociferations of joy, shrieks of fear” and “expressions of applause” that advanced the dominant colonial narrative.

Ascent of a Balloon in the Presence of the Court of Charles IV by Antonio Carnicero, 1783

Although explorations in sound were one of the many goals to legitimize the balloon as an instrument in modern natural philosophy, the scientific utility of the balloon succumbed to spectacle and entertainment. Early aeronauts tried to use their voices and speaking trumpets to sound the atmosphere and experiment with echo as a measurement of distance. Derek McCornack in his book Atmospheric Things, says that these balloonists were most of all “generating a sonorous affective-aesthetic experience” with the atmosphere. Along with scientific tools, balloonists often ascended with musical instruments and, in other instances, the balloon itself became the stage for operatic performances. More than a century before modern composers had transformative encounters with silence in anechoic chambers, aeronauts had already described its subjective qualities and effects in detail. In 1886, the photographer John Doughty and reluctant balloon traveler, while floating in a silent ocean of air, recalls hearing only two bodily sounds: “the blood is plainly heard as it pulses through the brain; while in moments of extra excitement the beating of the heart sounds so loud as almost to constitute an interruption to our thoughts.”

Travels in the Air, James Glaisher, 1871

PROBE /

I feel like a balloon going up into the atmosphere, looking, gathering information, and relaying it back. Rachel Rosenthal, 1985

The first untethered balloon ascents happened between 1783 and 1784. In current literature, this period is most cited for the patent of the steam engine, the beginning of the carbonification of the atmosphere by the burning of coal, and the start of the Anthropocene. In the industrialized society, the balloon floats through irreversibly modified atmospheres. “We are still rooted in air,” writes Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos. However, this air is partitioned and engineered to facilitate consumerism, war, terror and pollution.

Contemporary art practices using the balloon address some of these concerns. The balloon functions as an atmospheric probe that reveals “invisible topographies” and “politics of air” such as human interference, air quality, air ownership, borders, surveillance and the privileges of buoyancy. As a playful, non-threatening object, the balloon can elicit practices of inclusivity (e.g. balloon mapping) and affect. The transmission and reception of sound and music through the balloon help manifest air’s qualities and warrants artistic and social encounters with weather systems.

“Travels in the Air” by James Glaisher, 1871

During the 6th Annual Avant-Garde Festival parade going up Central Park West in 1968, the body of the cellist Charlotte Moorman rose a few feet above the floor attached to a bouquet of helium-filled balloons. This led the police to chase her and demand an FCC license for flying, to which Moorman replied: “I’m not flying – I’m floating.” Moorman was performing a piece called Sky Kiss, conceived by the visual artist Jim McWilliams that involved cello playing suspended by balloons.

In an interview for the book Topless Cellist by Joan Rothfuss, McWilliams explains that the original concept of Sky Kiss was to sever the connection between the cello’s endpin and the floor and expand the idea of kiss to an aerial experience. According to Rothfuss, McWilliams intended this piece to be an expression of the ethereal. But Moorman preferred the playfulness and the communal experience of the airspace. Instead of avant-garde music, she played popular tunes like “Up up and away” and “The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze.” Dressed with a super-heroin satin cape, Moorman infused Sky Kiss with humor and visual spectacle, posing a challenge to the restrictive access to buoyancy.

Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik, Sky Kiss by Jim McWilliams, above the Sydney Opera House Forecourt, 1976, Kaldor Public Art Project 5, Photo by Karry Dundas

Furthermore, Charlotte Moorman collaborated with sky artist Otto Piene to establish the right quantities of lighter-than-air gas to reach higher altitudes. Otto Piene, was a figure of the postwar movement Zero and coined the term Sky Art to describe his flying sculptures, multimedia balloon operas, and kinetic installations. For Piene, a child growing up during World War II, “the blue sky had been a symbol of terror in the aerial war.” The balloon collaboration between Charlotte Moorman and Otto Piene was a form of acknowledging aerial space in a musical and peaceful way. In his manifesto Paths to Paradise (1961), Piene questions: why do we have no exhibitions in the sky?(…) up to now we have left it to war to dream up a naive light ballet for the night skies, we have left it up to war to light up the sky.

Phil Dadson’s work Breath of Wind (2008) lifts an entire brass band of 24 musicians into the sky with 17 hot-air balloons. Brass instruments, usually associated with moments of revelation in religious texts, serve here as a calling for an aesthetic experience of wind and air currents. Since 1970s, Dadson’s environmental activism has brought forward sonic tensions between the human subject and Aeolian forces, as in Hoop flags (1970), Flutter (2003) or Aerial Farm (2004).

Similarly, the artist Luke Jerram displaces the experience of a concert hall to the sky. His project Sky Orchestra comprises of seven hot-air balloons floating across a city with speakers playing a soundscapes design to induce peaceful dreams. The hot-air balloon orchestra ascends at dawn or dusk so the airborne music can reach people’s homes during sleep or while in states of semi-consciousness. The sound-targeting of residential areas during periods of dimmed awareness exposes the entangling capacities of airspace, and the vulnerability of the private space.

Artist and architect Usman Haquem utilizes a cloud of helium balloons as a platform to identify and sonify changes in the electromagnetic spectrum. This project, Sky Ear (2004), reveals our meddling with the urban Hertzian culture via mobile phones and other electronic devices. Andrea Polli’s environmental work features sonifications of data sets captured by weather balloons. These sonifications provide audiences an emotional window to frame complex climate data. In Sound Ship (descender 1) by Joyce Hinterding and David Haines, an Aelion harp is attached to a weather balloon that ascends into the edges of space. The result is a musical trace of the vertical volume of our atmosphere and the sonification of masses of air as the balloon journeys upwards.

Haines and Hinterding, Sound Ship (decender1), 4-min extract, 2016

Yoko Ono and John Lennon created similar exercise in sounding in the film Apotheosis (1970). A boom microphone and camera attached to a hydrogen balloon ascends over a small English town documenting a sonic geography of the upper air. The artists stay in the ground as the balloon rises. In a period of great media spectacle, the couple choses to stay with trouble while balloon records Earth’s utterances slowly fading into atmospheric silence.

It is important to note that these musical and sound based works that expose the physicality of air movements and assemble affective meanings with atmosphere and weather systems are not particular to contemporary practices. The scholar Jane Randerson draws attention to indigenous modes of knowing and sensing air and the weather that incorporate sounding instruments. In Weather as Medium, Randerson writes: “in Indigenous cosmologies, the sense of interconnectedness “discovered” in late modern meteorological science merely described what many cultures already sensed and encoded in social and environmental lore.”

The balloon has a lighter than air object mediates our relationship with the airspace and offers opportunities to expand our aerial imagination. By sensing changes in the atmosphere, the balloon is a platform that generates knowledge and can help us experiment with new forms of being-in-air some inclusive and empowering, others much more invested in exclusivity sounded through the rare air of silence and the silencing power dynamics fostered via the view from above.

—

I would like to express my immense gratitude to Jennifer Stoever for editing this paper and for sharing her scholarship and input on this article. Thank you to Phil Dadson for sharing his video.

—

Featured Image: Scientific Balloon of James Glaisher, 1862, Georges Naudet Collection, Creative Commons

—

Carlo Patrão is a Portuguese radio producer and independent researcher based in New York city.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Instrumental: Power, Voice, and Labor at the Airport – Asa Mendelsohn

Botanical Rhythms: A Field Guide to Plant Music -Carlo Patrão

Sounding Out! Podcast #58: The Meaning of Silence – Marcella Ernest

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig: