Ajol, une plateforme franco-anglaise sans filtre en français

Résumé

La plateforme publie 524 revues issues de 32 pays d’Afrique. 39 revues sont en français. Malgré ce contenu francophone, Ajol ne dispose pas un filtre pouvant repérer les revues en français. Pour y arriver, il faudrait d’abord reconnaitre ou repérer les pays francophones sur la liste à sa page, Une. De plus l’on remarque que la plateforme est unilingue.

Visité par plus 200.000 personnes par mois, AJOL est une plateforme qui a été créée en 1998 à Oxford en Angleterre. Sa mission est de mettre à disposition du public en ligne une collection de publications des recherches académiques en provenance d’Afrique. D’importants domaines de recherche en Afrique (Biology & Life Sciences, Health, General Science, etc.) ne sont pas connus dans des publications de pays développés. Pour AJOL, Internet est un bon moyen d’augmenter l’accès à ses recherches afin de permettre aux chercheurs du monde entier. Le site de AJOL héberge 524 revues avec169 652 articles en texte intégral de 32 pays. De nos jours, son siège social se trouve en Afrique du Sud (Ajol, 2019). Deux types de frais d’accès qui permettent d’accéder aux articles non open access sont accordés aux chercheurs et aux étudiants d’une part, et un autre aux bibliothèques et cela en fonction du pays où la demande est émise.

Dans ce travail nous présentons les activités de Ajol. Notre démarche repose sur le protocole d’évaluation de The Charleston Advisor. il stipule que l’on que : «As a critical evaluation tool for Web-based electronic resources, The Charleston Advisor will use a rating system which will score each product based on four elements: content, searchability, price and contract options/ features» (The Charleston Advisor, 2019).

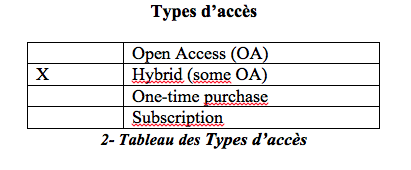

AJOL est une plateforme hybride. De ses 524 revues, 262 sont en accès libre. Le système AJOL est entièrement basé sur des logiciels et des technologies Open Source en l’occurrence : Open Journal Systems developed de Public Knowledge Project (PKP) au Canada, Operating System, etc. AJOL n’accepte pas les publications des auteurs de façon individuelle. Il faut passer par une revue pour être publié (AJOL, 2017 (a)).

Options de tarification

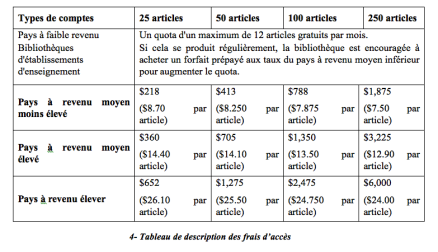

Les frais de publication proposés pour le téléchargement des chercheurs, des étudiants, etc. (AJOL, 2017 (e)). Ce sont :

Pour les bibliothèques ont leurs frais qui sont différents de ceux des chercheurs (AJOL, 2017 (d)).

Aperçu du produit / Description

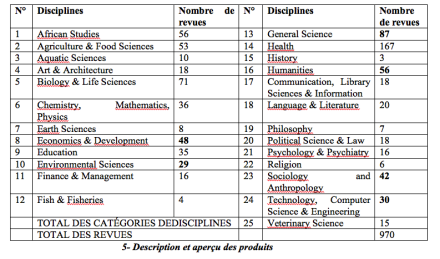

Deux produits sont mis à la disposition à la disposition du public: des publications payantes et non payantes. AJOL publie 169 652 articles en texte intégral dont 110 502 sont en accès libre. Ces articles sont issus de 527 revues, dont 262 en accès libre (AJOL, 2017 (a)). 25 disciplines reparties.

Les disciplines contenues dans leurs publications les suivantes :

L’on constate que 6 nouvelles revues (en gras dans le tableau ci-dessus) se sont ajoutées depuis 2017 au niveau des champs :

– des Sciences environnementales : 29

– de la Sociologie et de l’anthropologie : 42

– de la Technologie, de l’informatique et de l’ingénierie 30

– des Sciences générales : 87

– de l’Économie et du développement : 48

– Sciences humaines : 56

Les champs de la santé (Health (167)) et de (General Science (87)) arrivent en tête du nombre des catégories de sujet et sont toutes évalués par les pairs (peer reviews). AJOL s’adresse spécifiquement aux chercheurs et aux bibliothèques. Selon les auteurs du site Web, AJOL a un PageRank Google de 8. Il est visité par 200 000 personnes par mois à travers le monde. L’onglet «Using AJOL» permet d’accéder la feuille de route qui indique le processus de recherche (AJOL, 2017 (b)).

Interface utilisateur / Navigation / Recherche

La plateforme publie 524 revues issues de 32 pays d’Afrique. 39 revues sont en français. Malgré ce contenu francophone, Ajol ne dispose pas un filtre pouvant repérer les revues en français. Pour y arriver, il faudrait d’abord reconnaitre ou repérer les pays francophones sur la liste à sa page principale. De plus l’on remarque que la plateforme est unilingue.

Une particularité est que son interface donne accès facilement aux produits. La fonctionnalité «Journal» donne directement accès aux différentes catégories de sujets qui sont traités. On peut les obtenir par pays sur une facette où tous les pays sont affichés. Et les facettes par pays permettent de spécifier sa recherche. Toutefois, les informations sur les auteurs et les rédacteurs de la plateforme sont inexistantes. Par exemple, l’on n’a pas les noms et l’organigramme de cette organisation à but non lucratif (The Charleston Advisor, 2019).

Le site web de AJOL demande une inscription pour naviguer sans restrictions. Au niveau de la principale, 5 onglets permettent de se connecter. «Afriacn Journals Online (AJOL)» est fixé sur la page une. L’onglet «Journals» conduit à la liste des catégories de publication, «Advanced Search» ouvre sur un champ de recherche plus spécifique par facettes. «Using AJOL» permet de trouver des articles en accès libre de toutes les catégories de revues par titre, d’enregistrer le profile de votre revue et de donner une feuille de route pour les recherches.

Ajol donne une occasion aux différentes de s’enregistrer et diffuser leurs propres articles. Il indique aussi la liste des frais que chercheurs et auteurs doivent payer. «Ressources» connecte les visiteurs sur d’autres revues hors de l’Afrique. Par ailleurs, une colonne à facette située à droite du site indique les catégories, par ordre alphabétique et par pays où l’on peut télécharger les articles (AJOL, 2017 (a)).

Contenu

Ajol a pour mission de valoriser et de diffuser les publications africaines. Dans ce sens, la plateforme remplit parfaitement ses objectifs. Elle diffuse 524 revues examinées par les pairs, dont plus de la moitié (306) avec des frais pour le téléchargement. Le reste est en accès libre. On remarque que la grande partie est en anglais (497). 39 revues en français. Bien que le contenu soit diversifié, les études sur les Sciences de l’Information et de la bibliothéconomie sont très restreintes (18 revues avec la Communication) par rapport aux sciences de la santé (167).

Tarif

Les revenus provenant des frais de téléchargement de l’article pour les revues d’abonnement sont envoyés au journal d’origine (moins le coût d’amortissement d’AJOL). Par contre toutes les revues en accès libre sont à la portée de tous. Les frais sont fixés en fonction des pays. Les pays pauvres payent moins que les plus riches. Les critères qui définissent ces pays sont basés sur les statistiques de la Banque Mondiale (The World Bank, 2017). Évidemment, les frais des bibliothèques sont plus élevés que ceux des chercheurs et cela en selon les pays.

Par ailleurs, une des compétitions de AJOL est The Sabinet African ePublications (African Journal online archive). Son site publie 500 revues regroupant 64 catégories de sujets, dont 86, en Open Access. Il est créé depuis 2001. Cette plateforme a la particularité de ne pas publier son organigramme comme AJOL. Nous n’avons pas retrouvé ses frais de publication. Par contre, elle publie un grand nombre de revues de l’Afrique du Sud (The Sabinet African ePublications, 2017).

La bibliothèque numérique en ligne africaine (AODL) est un portail de collections multimédia sur l’Afrique. Les auteurs collaborent avec le Centre d’études africaines de l’Université d’État du Michigan, ainsi que des organisations du patrimoine culturel en Afrique pour construire cette ressource (AODL, 2019).

Dispositions d’achat et de contrat

Les revues qui choisissent de publier dans un modèle d’accès ouvert ont leur texte complet en ligne pour le téléchargement gratuit. Les bibliothèques peuvent ouvrir un compte de téléchargement d’articles prépayés avec AJOL pour accéder aux titres des partenaires qui facturent leur contenu. Cela permet aux utilisateurs d’obtenir plus facilement des articles en texte intégral auprès de AJOL. L’accès aux articles d’abonnement est effectué par un mot de passe ou par leur logiciel qui sélectionne automatiquement la gamme d’adresses IP au choix de l’établissement. Des indications expliquent qu’il n’y a pas de restriction de temps pour la remise des articles. Les comptes peuvent être complétés à tout moment. Pour vérifier la catégorie dans laquelle votre pays se trouve, il est demandé de se référer listes de pays de la Banque mondiale. L’adresse suivante : info@ajol.info permet aux revues de se faire créer une installation un compte.

Conclusion

La plateforme AJOL est hybride, certains articles sont payants. Pour gérer le flux de clients, une souscription exige un «username» et un mot de passe pour la navigation sur le site. De plus, l’accession aux documents payants sont soit par abonnement ou directement. Ce qui filtre les visiteurs. Il y a un panier dans lequel tout souscripteur peut collectionner les articles qu’il souhaite acheter. Il n’y a pas d’options qui déterminent un groupe particulier avec des faveurs spécifiques.

Références

AJOL, (2017) (a). African Journals Online (AJOL)) (2017). http://www.ajol.info/ Visité le 30/102019

AJOL, (2017) (b). African Journals Online: Browse by Category. http://www.ajol.info/index.php/index/browse/category Visité le 30/102019

AJOL, (2017) (c). FAQ’s http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajol/pages/view/FAQ#A1 Visité le 30/102019

AJOL (2017) (d). How Librarians can use AJOL. http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajol/pages/view/LIBhowto . Visité le 30/102019

AJOL, (2017) (e). How Researchers can use AJOL http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajol/pages/view/RESHowto Visité le 30/102019

The Sabinet African ePublications (2017). http://journals.co.za/. Visité le 30/102019

The African Online Digital Library (AODL) (2017). http://www.aodl.org/ Visité le 30/102019

The Charleston Advisor, (2017) About TCA. http://www.charlestonco.com/index.php?do=About+TCA Visité le 30/102019

The World Bank (2017) Data and Statistics. http://econ.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/DATASTATISTICS/0,,contentMDK:20421402~menuPK:64133156~pagePK:64133150~piPK:64133175~theSitePK:239419,00.htmlVisité Visité le 30/102019

SO! Amplifies: Die Jim Crow Record Label

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!

SO! Amplifies. . .a highly-curated, rolling mini-post series by which we editors hip you to cultural makers and organizations doing work we really really dig. You’re welcome!Die Jim Crow (DJC) is the first US record label dedicated to recording formerly and currently incarcerated musicians. The mission of DJC is to provide formerly and currently incarcerated musicians a high-quality platform for their voices to be heard. DJC sprang from Executive Director Fury Young’s communications with currently incarcerated individuals by letter and was originally slated to be a single concept album, inspired by Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow and Pink Floyd’s The Wall. The project quickly grew into much more than that.

For me, death to Jim Crow means a death to stereotypes, to misconceptions of the ‘Other.’ There is no Other. The term ‘Jim Crow’ comes from a song which satirizes a slave. I see much parallel to the way our society views those incarcerated: that they are ‘lesser than;’ merely criminals. We are changing this narrative through music. – Fury Young

DJC records, produces, and releases music written and performed by formerly and currently incarcerated individuals. Prison staff and others working inside, such as volunteers or other program facilitators, refer incarcerated collaborators to DJC. Executive Director Young and Deputy Director BL Shirelle correspond by mail or digitally with these individuals to help prepare their musical contributions for in-prison recording sessions. Young, Shirelle, and other producers identify promising Project Managers inside each facility who help guide the music creation and recording process.

Music is recorded in prisons, homes of the formerly incarcerated, and Brooklyn studio revolutionsound, produced in the same studio, and then widely released through digital and physical channels. We currently have ongoing programming at 2 prisons in South Carolina and have recorded at a total of 5 prisons since 2015, 3 of which we are seeking to regain access to because of prison administration changes.

Our Board of Directors comprises 40% formerly and currently incarcerated individuals, ensuring that Die Jim Crow is steered by those who have direct lived experience with the issues informing our work. Deputy Director Shirelle is a formerly incarcerated musician acting as co-Label Manager with Young, bringing her unique set of experiences and talents to Die Jim Crow.

Over the past several years, Young has formed solid relationships built on trust with a number of formerly and currently incarcerated artists and has learned how to navigate the challenging process of gaining access to prisons to work with incarcerated individuals. As Fury told SO!’s Managing Editor Liana Silva,

Gaining access is tough. It can take months, even years to navigate through to the right people and get an Okay. Once you’re in, you’re in. But then you need to deal with censorship from the top brass and navigating through that. There are all types of unforeseen challenges that pop up when you least expect them to — but it really comes from above. In terms of recording on the inside, besides the typical band shit like “this guy’s ego is getting in the way” or “this guy won’t play with the band,” the making music part is the fun part.

Earlier this year–March 2019–Young took a trip to Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina, the experience inspired a big shift In Die Jim Crow toward founding the non-profit label. The journey began in New Orleans with a home recording of Albert Woodfox, who lent his voice to music for the first time. Mr. Woodfox spent 43 years in solitary confinement in Louisiana, the longest of any solitary prisoner in US history. Fury also recorded a video interview with Albert about his experiences with music while inside.

From NOLA, Fury picked up co-producer and engineer Doc (aka Dr. Israel) in Mississippi–who has been part of the DJC team since 2015– where they spent two days recording four rappers at a juvenile prison — Central Mississippi CF Youthful Offender Unit. They spent the next 10 days in South Carolina recording a total of 22 artists at a men’s and a women’s prison: Allendale CI and Camille Griffin Graham CI. When they got home, Fury noted at a Board of Directors meeting: “This is becoming a record label.” He had already discussed it with Shirelle and senior advisor Maxwell Melvins, both DJC artists and board members, and the consensus was clear. A similar reaction was palpable at the board meeting. Stefanie Lindeman, a non-profit veteran and board member, brought up, “OK, we need to put together a three year strategic plan immediately.” And from there, Die Jim Crow Records was born.

And what will Die Jim Crow records sound like? Fury told SO! that

There’s a lot of hip hop and soul. Most of our artists are black and that is the music many of them grew up on. But as we transition into a record label and open up to new projects, we’re becoming more of a melting pot. All types of influences go into the stew. Right now we’re working on a straight hip hop EP at a women’s prison in South Carolina — kinda like a Lauren HIll/Rapsody vibe, and then a project called The Masses at a men’s SC prison — which has a full band and several emcees. They’re sorta like The Roots meets Wu Tang in a southern prison. But in other states we’ve recorded plenty of rock and even Native American chants. If you listen to the EP, you’ll get a sense of the sundry sounds.

Young has already recorded and released a high-quality EP with these musicians and recorded a significant library of unreleased music.

Over the next few years, DJC will continue to grow through re-releasing and repackaging existing content, cultivation of current and new artists, and development of new projects, as well as live shows, events, and tours. DJC will release 1 EP and 1 mixtape per year. The first release will be the Die Jim Crow LP, accompanied by a book and feature film documentary in 2022. By November 2020, DJC will release The Masses EP. On May 1, 2020, DJC will re-release the Die Jim Crow EP, release the “First Impressions” single and video from the EP, and begin the “Single of the Month” initiative, putting out both prerecorded songs and new works.

Die Jim Crow is currently engaged in a Kickstarter campaign for their project through 8 pm tonight, Monday 28, 2019– click here to donate to launch the label and/or read (and hear) more about the project!

—

Featured Image: Some of the artists Die Jim Crow has worked with in GA, OH, IN, CO, PA, CA, NY, NJ, MD, KS, AL, TX, and LA. (L-R each row): Johnnie Lindsey, Leon Benson, Malcolm Morris, Maxwell Melvins, Michael Austin, Dexter Nurse, Valerie Seeley, Spoon Jackson, Tameca Cole, Michael Tenneson, Mark Springer, Obadyah Ben-Yisrayl, Cedric “Versatile” Johnson, Lee Lee, Anthony “Big Ant” McKinney, Ezette Edouard, Pastor Anna Smith, BL Shirelle, Carl Dukes, Norman Whiteside, Sedrick Franklin, Charles “C-Will” Williams, Apostle Heloise

—

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND!…If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Regulating the Carceral Soundscape: Media Policy in Prison—Bill Kirkpatrick

Prison Music: Containment, Escape, and the Sound of America—Jeb Middlebrook

SO! Podcast #75: Wring Out Fairlea—Emma Russell

SO! Amplifies: Carleton Gholz and the Detroit Sound Conservancy

Ruben Brave reports from post-truth conference in Malta

By Ruben Brave

On October 10/11 2019 I presented our applied science project Make Media Great Again (MMGA) at the Post-Truth Society from Fake News, Datafication and Mass Surveillance to the Death of Trust conference on Malta; an initiative of new media teacher of the University of Malta and founding Director of the Commonwealth Centre for Connected Learning, Alex Grech. The Post-Truth conference included speakers from The Economist, Worldbank and Google.

In my talk I not only summarized how participatory journalism can be a cost-effective and inclusive solution for quality control in online publishing but also indicated how MMGA’s curated process leads to reciprocity and reflection.

The atmosphere on the Malta conference seemed a starting point for higher awareness and consciousness of the roles and responsibility all agents have on the internet when it concerns mis- or disinformation, the two pillars of fake news.

The very real impact of fake news on people’s lives was evident by at least two situations at the Post-Truth event. First, a kaleidoscopic situation occurred when a keynote speaker and Middle East blogging pioneer, who was imprisoned for 6 years, was publicly (verbally) attacked from the audience and was accused of spreading fake news himself; fake news that allegedly had supported other people getting incarcerated or even worse.

Also, a moderator (and journalist) was under police surveillance during the event as he/she had key information concerning the offender(s) on the murdered Maltese Panama-papers journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia; a societal disruptive case due to the various investigations with an abundance of dubious reporting to the public. The social indignation concerning the handling of the Galizia case erupted at several unexpected moments on the event.

Fake news leads to real problems and is tied to social injustice. What can we do as citizens? Read my media-enriched talk below:

Public Rebuttal, Reflection and Responsibility – An Inconvenient Answer to Fake News

I’m co-founder of Make Media Great Again [3], shortened called MMGA, a Dutch non-profit initiative [4] focussed on providing a possible part of the solution concerning fake news. A Dutch project with an (according to some people) funny name [5] but with a serious mission.

What do we do at MMGA? Collaborating with publishers and community to fight misinformation. We improve the quality of media together with their pool of involved readers, viewers and listeners. We have built a transparent system for actionable suggestions and specific remarks from this community pool. NU.nl (translated as NOW.nl) with 7 to 8 million visitors a month and by far the most important news service in the Netherlands is our test partner [6]. We test with a group of critical and knowledgable NU.nl readers (called ‘annotators’) [7] who offer suggestions to increase the journalistic quality through the balanced use of sources and clearer transfer of information.

And when I talk to my American friends [8] about Make Media Great Again they all agree what a great potential our endeavour has. But also they echo their main remark:

Change the name, change the name, change the name.

And to be fully honest to a large extent I must agree with this. Because for some reason, we keep getting enthusiastic emails with subjects such as: “Yeah let’s build that wall!” [9]

But nonetheless, we are not changing the name, not yet…

My personal realization for the need for MMGA started when I was confronted with “fake news” on the publicly funded national NOS website, the Dutch Broadcasting Foundation. For some of us, it might not be a surprise that a state-funded medium spreads wrong information but in the Netherlands people still put a lot of trust in them.

The case was quite remarkable. During election period the website reported that the frontman of the Labour party was asking questions in Parliament about ethnic profiling by the Dutch police. [11]

figure 1: example of misinformation on the website of the national Dutch Broadcasting Foundation concerning a political party asking Parliamentary questions concerning ethnic profiling by the Police in the Netherlands

After investigating the Parliament website and ultimately asking the Registry what these questions actually were, I got an email that the Labour Party did not at all had asked questions about ethnic profiling. It seemed that a female member of Parliament of the Democratic Party with a migration background had asked the relevant questions.

figure 2: update on Dutch Parliament website concerning the party and person that did ask questions concerning ethnic profiling by the Police in the Netherlands

This information could have impacted voting behaviour, at least it influenced mine. When I confronted the Dutch Broadcasting Foundation and asked if they would at least consider editing the headline of the concerning article the editor-in-chief responded agitated with the remark: “I’m not going to contribute to history falsification!”

How curious…

And how can anyone tell these days what is factually accurate and what isn’t? What is formulated to reveal and what is written to conceal or even to mislead? These are increasingly pressing questions, especially as a new historical round of disinformation is upon us and ‘fake news’ is flourishing in all its glory. Could critical readers help in improving the reliability of “our information”?

Our society would benefit from better news. Yet we don’t have the tools to improve this ourselves. This has changed with our open-source movement MMGA as we offer transparent tools for journalistic reporting. Where everyone can contribute and we invite everyone to join our cause. For a clearer world.

Up to 50,000 readers were involved in our first pilot, with candidates individually selected from the news organization’s readers’ commentary panel (their forum NUJij). From these readers, more than 300 are now registered as an annotator.

figure 3: screening, selection and training process overview

And from this group, we selected, screened, and trained knowledgeable and/or critical thinking readers to actually work on annotation assignments.

How we do it? Improving the quality of media through annotations? Well, we believe people have unique, diverse views and also relevant knowledge that helps the editorial process and quality. With our digital tools, people are able to detect misinformation, biased language and false contextualization. MMGA annotations are practicable suggestions, labelled notes, directly attributed to words, sentences or paragraphs. They are actionable for the editor, avoid debate based on personal preferences and, if correct, directly trigger a correction within articles.

Editors are free to implement or not. Because the annotations are immediately executable and based on the principle of journalistic objectivity, they overcome the known issue of lengthy debate due to subjectivity that arises with regular reader comments. The system differs from the well-known response form, whereby the reaction usually concerns disagreement with the online paper’s opinion or the tenor of the whole article. Annotations focus on specific elements of an article and are structured according to annotation labels. Our tests not only were to test the annotation system itself but also see how those involved respond to and work with it.

Furthermore, provided these annotations are clear, factually accurate and presented with proper transparency, they provide the necessary motivation for their immediate implementation, given that doing so will only improve the quality of the work in question.

Why we do it? To improve the credibility of media and strengthen the bond with their audience. The credibility of the media is being questioned more and more, whereas the media are seen as the first party to protect us from wrong information. This fundamental role of media is essential to enable proper functioning of democracy and constructive social debate, thus fortify social cohesion.

The potential of this idea goes beyond journalism; in fact, any organization or body that provides information as a ‘public service’ could benefit from it, be they governmental institutions or museums. And it is arguably becoming increasingly important to use the openness of the internet to facilitate the representation and participation of diverse and hitherto underrepresented groups in media and society at large.

Editorships, newsrooms and the army of opinion leaders typically reveal a skewed distribution in their composition with respect to gender and place of origin and residence, among other things. Whereas MMGA, with its “diversity panels” geared towards the nuanced use of language in journalism and its emphasis on multiple perspectives in reporting, holds the possibility of genuine balance. True quality is arguably impossible without diversity. We find it important that our group of annotators is as diverse as possible. Men, women, people from various ethnic backgrounds and minorities of all sorts. This minimises the chance of overlooking particular contexts. A more diverse group can, according to scientific research ([12] see pages, 21, 31 and 38), improve the quality of news offerings and build trust in the sources of these offerings. Trust, in particular, is now one of the major issues in mainstream journalism. The study that yielded the findings involved globally recognized names such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the BBC and, last but not least, The Guardian. We, therefore, invite anyone who shares our concerns and wants to help to contact us [13].

MMGA sees diversity as a means of improving the quality of published content, rather than an end in itself.

The fact that media organizations themselves are beginning to admit the need to fight fake news to maintain their readership’s trust opens the door for collaborations. And this is how we hope to work, too. After all, the idea isn’t to destroy existing organizations but to improve the quality of what they produce.

So there you have it! MMGA is cost-effective (because we mainly work with volunteers) and a value-added layer of contributors who create a safety net against misinformation, thus giving the hardcore fake news no change. We collaborate with universities, well-known investigative journalists and impactful media for a maximum reach [14]. Solution found it’s even politically correct because it’s all-inclusive… Yep, case closed… Couldn’t anybody else come up with this? Oh well. No problem, we got it covered…

At least… we thought. Before the post-truth reality punched me in the face!

It happened to me when I was vigorously watching a new tv series: The Man in the High Castle [15].

Figure 4: poster tv-series Man in the High Castle

An American alternate history television series [16] depicting a parallel universe where the Axis powers (Rome–Berlin–Tokyo-axis) win World War II – so the Nazis and their partners won instead of the Allies. It is produced by Amazon Studios and based on Philip K. Dick‘s 1962 science fiction novel of the same name [17]. Dick is popularly known as the writer of the books behind movies as Blade Runner and Minority report.

Side-note: As Ta-Nehisi Paul Coates, national correspondent for The Atlantic, states that for a lot of African-Americans the world Philips K Dick sketches has a lot of resemblance with their actual reality. But also other more general ethical questions Western society currently has in “our reality” are addressed.

So back to me and the series. During the period I’m binge-watching the series I’m using Facebook and there – for some reason – I’m directed to a journalistic looking Facebook-post with the purport that Bill and Melinda Gates are not trying to save the world from malaria or polio but instead actually are testing experimental medicines (on behalf of large pharmaceutical companies) on poor Indian kids…just like the Nazi’s would do!

And I must be honest, for a second I felt the rage and indignation coming up inside of me. This was big news! The world needed to know about this. And I was ready as ever to share this post with my friends and relatives. To shine the light on this wrongdoing and work to a clearer world.

But then I remembered MMGA’s code of conduct, inspired by the journalistic ethical code the Bordeaux Declaration, multiple Dutch guidelines concerning journalism and prevention of improper influencing by conflicts of interest and last but not least the Five Pillars of Wikipedia. Our first directive states:

“Your annotations are based on facts for which you can indicate a reliable source (which thus are verifiable and can be held accountable), as completely as possible and regardless of the opinions expressed about this source.”

I couldn’t even find one reliable source backing up the claims made in the Facebook-post. Thus even so how much I felt I was obliged to spread this “news” I also did not want to have the responsibility for an unverifiable article.

And this reminded me of the results of one of the first MMGA tests we conducted concerning our Trustmark on 500 random internet users. The Trustmark signifies and guarantees that all articles are under audit of an independent community, sources are easily viewable to the public and any alterations to the article are also tracked and viewable by the public.

figure 5: test results adoption indication MMGA Trustmark

To create more transparency and trust. From our survey with these 500 readers, nine out of ten stated they experience an article with a Trustmark as more trustworthy. Also, more than 6 out of ten were likely to share an article with a trust mark.

figure 6: overall function MMGA Trustmark

So what will happen when people become more aware when such trustmarks are missing in the article they are reading? Would they be more conscious when they are sharing unmarked articles?

Without the network effects of the Internet wrong information would probably have the same damaging effects as simple “false gossip” in the contained context of let’s say a school class. We are keen to look at platforms such as Facebook and news media like the Dutch Broadcasting Foundation as guilty parties for the fake news problem. And reach for all kinds of tech-related solutions to save us.

But based on my own Man in the High Castle experience I suspect we still need to make a leap in our societal consciousness if we are going to survive this post-truth era:

“We are not merely using the technical infrastructure of the internet, as if it is something outside of us. Beyond our own power and responsibility. We are an integral and decisive part, the living nodes, of this global information network.”

figure 7: Quote of Daphne Caruana Galizia at the protest memorial in Valetta on the night before the conference

And therefore the name of our organisation stays as it is. To remind us of the easily overlooked fact, another inconvenient truth, that we all individually have to play our part – as reflective and responsible citizens – to make media great again.

Figure 8: MMGA co-founder Ruben Brave being interviewed at the post-truth conference “From Fake News, Datafication and Mass Surveillance to the Death of Trust” held 10-11 October 2019 in Valetta on Malta. Copyright photo’s by Harry Anthony Patrinos, Practice Manager World Bank for Europe’s and Central Asia’s education global practice.

Arima, an African journal in HAL archives

Original:

Kakou, T.L. (2019). Arima, une revue africaine dans Hal archives. Soutenir les savoirs communs. https://sustainingknowledgecommons.org/2019/10/23/arima-une-revue-africaine-dans-hal-archives/

English synopsis by Heather Morrison

African journals seek to create a space for themselves by disseminating their journals through online platforms and archives. There are multiple possibilities for preservation and publishing on line. One of these is electronic archiving. In this research post Kakou presents the HAL archive and explores the representation of African document. Developed and administered by the Centre pour la Communication Scientifique Directe (CCSD), the platform HAL is an open archive in Social Sciences. In this post, Kakou presents an overview of the services offered by HAL, including Episciences.org and Sciencesconf.org. Episciences.org offers journal publishing within the archive and supports the innovative peer-review overlay approach to journal publishing. Arima, a journal that has been supported by the North-South coalition Colloque africain pour la Recherche en Informatique et mathématiques appliquées (CARI) for twenty years, is among the 15 Episciences journals. This is « our » platform too ; Morrison’s 2018 ELPUB OA APC survey can be found in Episciences.

OpenEdition and French language African scholarly journals

Original:

Kakou, T.L. (2019). OpenEdition et les revues savantes d’Afrique. Soutenir les savoirs commun. https://sustainingknowledgecommons.org/2019/10/23/openedition-et-les-revues-savantes-dafrique/

English synopsis by Heather Morrison

OpenEdition (formerly Revues.org) publishes 21 African journals. Only one of these journals is published in an African country (Kenya). In this post Kakou illustrates a gap in dissemination of African scholarship, particularly francophone African scholarship. For example, of the 524 journals included in African Journals Online (AJOL), 465 (89%) are published in English speaking countries and only 39 (7%) in French speaking countries. Only 12 of the 24 African countries where French is an official or co-official languages are represented in AJOL. This research illustrates the African and particularly Francophone African knowledge gap that is the focus of Kakou’s doctoral research.

Governing the Scholarly Commons (part 2)

Back in July we surveyed members of the Radical Open Access Collective on a possible decision-making model of lazy consensus. To quickly recap, lazy consensus is the process by which decisions are taken when no one disagrees with a proposal within a short(ish) window that takes into account numerous time zones and weekends. Anyone can propose an action and this motion can be debated until there are no further disagreements.

The idea of lazy consensus was well received on the mailing list and an interesting discussion ensued about the future our collective governance. Kathleen Fitzpatrick highlighted the need for community building – what she terms ‘social sustainability’ – as crucial to radical forms of collaboration. This underscores the need for ROAC members to get to know one another and to extend generosity and care to one another as far as possible. Joe Deville emphasised this with particular respect to the tone of our discussions, which should be ‘conducted in open, generous, caring ways’. Yet, as Endre Dányi kindly pointed out, there is a ‘certain sense of violence implied in claims about commonness and the common good’. We must be wary of not imposing on each other a predefined set of identities and values that we all share, instead keeping in mind that community itself necessitates difference or un-commonality (what Roberto Esposito would term a ‘common non-belonging’).

Following on from this discussion, one of the first points of action we would like to propose for the ROAC, is to implement the idea of lazy consensus with a 72-hour window for objections, while we will also ensure to stimulate discussion as much as possible. In practice, we do not envision any huge decisions being made about the collective and so it is likely that lazy consensus, as a decision making model, will only be intermittently used . Nonetheless, please feel free to propose ideas for the collective to consider – we really want to keep everything horizontal and informal to the greatest extent we can.

Related to this, during the mailing list discussion Gary Hall shared some helpful thoughts from his experiences helping to run a local community football club (and his reading of Barcelona En Comú’s Fearless Cities). Gary’s advice can be summarised as follows:

- Don’t be afraid to take the lead

- Ensure a gender balance and diversity from the start.

- Have generosity as a key value – collaboration requires individuals to be generous (with their time, energy, attention etc.).

- Try to reduce vertical hierarchies by distributing authority among as many people as possible

- Try to make it possible for everyone to feel they can contribute

Given that everyone is busy, and it is easy for initiatives like ROAC to lie dormant in particularly busy periods, we felt it would be worth instigating some of these approaches through a member advisory board, which we would like to put forward as our second point of action. The board would help generate and moderate discussion, admit new members and generally be a face of the ROAC in their own geographical/disciplinary area. We are keen to have broad geographical coverage from all across the globe, but we are especially interested in representation from Africa and Latin America (where a number of our members are based). Please email Sam and Janneke if you would like to get involved (and we might also nudge some of you who previously indicated you would be interested in this)! Going forward, and once we have an advisory board established, we can discuss whether we want to formalise this structure more.

Related to this, we are still keen to stimulate discussion on the mailing list by having themes set and moderated by different listserv members each month. Please get in touch if you would be interested in moderating discussions related to the future of scholar-led open access. You do not have to be associated with a member press or project, just interested in what we’re trying to achieve. We would ask that you post a question or topic to the list once a week for a month and then moderate the ensuing discussion. Open access week is of course a good time to start the discussion. Our friends at ScholarLed have been posting daily blog posts on the future of scholar-led publishing infrastructures, so perhaps one of us would like to try to drum up responses to these posts or follow them up for further discussion?

OpenEdition et les revues savantes d’Afrique

Parmi les revues que OpenEdition publie, 21 revues sont africaines. Elles sont localisées dans 5 pays. Seul un pays africain (Kenya) y figure. Ce sont : Nederland (1), Portugal (2), Kenya (1), France (17), Italie (1).

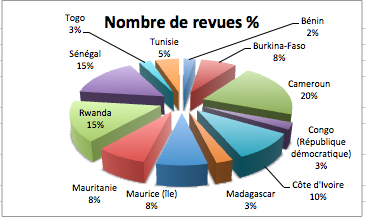

Les universités africaines adoptent les stratégies à suivre pour se développer au numérique. Selon Murray et Clobridge (2014), de plus en plus de revues en ligne sont diffusées sur les plateformes africaines telles AJOL, Sabinet, etc. La plateforme AJOL (African journals online) par exemple, se veut promotrice de la revue africaine en général. Cependant, l’on dénombre sur ce site, 39 revues en français (7%) sur 524 (Ajol, 2019). Ces revues sont reparties entre 12 états sur 24 (voir tableaux ci-dessous) dont le français est une langue officielle ou co-officielle (Université Laval, 2019).

Tableau 1 : Liste en % des pays cités dans Ajol

Tableau 2 : Liste des pays et nombre de revues en % des pays existants et non-existants sur Ajol

18 états anglophones détiennent la majorité absolue des revues avec 465 revues. D’autres pays (arabes (19), portugais (1)) se partage 20 revues. Voir Tableau.

Tableau 3 : Nombre de revues par pays en %

Tableau 4 : Nombre de revues par pays en %

Objectif

Notre objectif est de répertorier les revues africaines sur le Web et principalement sur les plateformes. Dans cette recherche, nous avons sélectionné la plateforme OpenEdition pour connaître les types de publications de revues africaines. Dans un premier temps, nous présentons la plateforme OpenEdition. Dans un deuxième temps, nous indiquons le nombre de documents qui y sont diffusés.

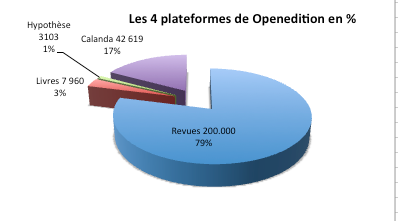

Les quatre plateformes d’OpenEdition

Au sortir de l’analyse de la plateforme Revues.org, nous observons que celle-ci devient: OpenEdition depuis 2017 pour renforcer sa dimension internationale. Elle publie quatre plateformes de publication et d’information sur les sciences humaines et sociales: OpenEdition Journals (les revues), OpenEdition Books (les collections de livres), Hypothèses (les carnets de recherche) et Calenda (les annonces d’événements académiques internationaux) (OpenEdition 1, 2019).

OpenEdition accueille 522 revues sur son portail. Environ plus de 200 000 articles, dont 92% sont accès libre (OpenEdition 2, 2019). Sur la plateforme OpenEdition Books, l’on dénombre près de 7 960 livres en sciences humaines et sociales provenant de 90 éditeurs. L’accès aux ouvrages se fait sur l’espace personnel de chaque éditeur. Ils sont librement accessibles en HTML, et imprimables (OpenEdition 3, 2109).

Quant à Hypothèses, 3 103 carnets de recherches sont recensés sous différents types et tous en accès libre. Ce sont : carnet de chercheur, carnet de terrain, carnet de séminaire, carnet de veille, etc. (OpenEdition 4, 2019).

Enfin, Calenda est le calendrier d’annonces scientifiques en sciences humaines et sociales. Il regroupe, plus de 42 619 annonces en libre accès. De plus, Calenda publie dans les actes de colloque, les programmes complets de journées d’études et de séminaires, les cycles de conférences, les appels à contributions en vue de colloques, etc. (OpenEdition 5, 2019). Voir tableau

Tableau 5 : Les 4 plateformes de OpenEdition en nombre d’articles et en %

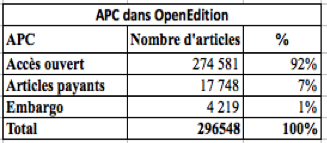

OPenEdition offre aux bibliothèques la possibilité de choisir une politique d’acquisition dans la logique de développement du libre accès. Aucun quota de téléchargement ne s’applique à cet accès (OpenEdition 6, 2019). OpenEdition publie 274 581 en accès libre. 17 748 articles sont payant et 4219 articles sous embargo. «L’abonnement donne accès aux fichiers PDF et ePub de manière pérenne» (OpenEdition 6, 2019). Voir tableau

Tableau 6 et 7 : APC dans OpenEdition en nombre d’articles et en %

Fig:6

Fig:7

Conclusion

OpenEdition publie 4 plateformes (Revues, livres, Hypothèses Calanda) soit un total de 253 682 publications. Les revues représentent 200 000 soit 79%. 274 581 (92%) sur 296 548 articles sont disponibles en accès libre. Parmi ces revues OpenEdition diffuse 21 revues africaines. Seul un pays africain y figure: le Kenya. Nous avons observé que OpenEdition est le nouveau nom de Revue.org.

Bibliographie

African journals online, 2018, https://www.ajol.info/ Visité le 13-10-2019

Murray, S. et Clobridge, A. (2014). The Current State of Scholarly Journal Publishing in Africa Findings & Analysis September 2014.

OpenEdition 3, Books, 2109, http://books.openedition.org Visité le 13-10-2019

OpenEdition 5, Calanda, 2019, http://calenda.org Visité le 13-10-2019

OpenEdition 4, Hypothèse, 2019) http://hypotheses.org Visité le 13-10-2019

OpenEdition1, Informations Journal, 2019,https://journals.openedition.org/10580 Visité le 13-10-2019

OpenEdition 2, Les services d’OpenEdition 2019, https://www.openedition.org/10918 Visité le 13-10-2019

OpenEdition 6, Services, 2019, https://journals.openedition.org/10179 Visité le 13-10-2019

Université Laval, 2019, Les États où le français est langue officielle ou co-officielle

http://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/francophonie/francophonie_tableau1.htm Visité le 13-10-2019

Arima, une revue africaine dans Hal archives

Résumé

Nous présentons dans cette recherche :Hal archives. Hal est une plateforme d’archives ouvertes. Elle conserve des revues sur sa plateforme Episciences.org sur laquelle l’on trouve une revue africaine Arima. Hal anime sur une seconde plateforme: Sciencesconf.org le programme des organisateurs de colloques ou réunions scientifiques.

Les revues africaines cherchent à se faire une place par la diffusion de leur journal sur les plateformes et les archives en ligne. Les possibilités de conserver et de publier en ligne sont multiples. L’une d’elles est l’archivage électronique. Dans cette recherche nous présentons Hal archive. Quelle est la représentativité des documents africains dans cette plateforme ? Développée et administrée par le Centre pour la Communication Scientifique Directe (CCSD), la plateforme HAL est une archive ouverte en Sciences de l’Homme et de la Société. Le CCSD entend diffuser et valoriser des publications et des données scientifiques en fournissant des outils pour l’archivage en ligne (CCSD 2, 2019). Dans ce travail, dans un premier temps, nous définissons deux termes épi-comité, épi-revues qui peuvent aider à la compréhension des termes utilisés pour indiquer certains produits. Dans deuxième temps, nous présentons Hal archive et les plateformes qu’elle publie.

Définition

Epi-revue :

Epi-revue est une revue électronique en libre accès. Elle est composée d’articles soumis via un dépôt dans une archive ouverte telle que HAL ou arXiv.

Epi-comité :

Epi-comité désigne le comité scientifique d’experts reconnus dans leur discipline. Les scientifiques sont chargés de stimuler la création des comités de rédaction pour l’organisation de nouvelles épi-revues et de veiller à la qualité de leurs contenus (Episciences 1, 2019).

Activité de Hal archive : Episciences.org – Sciencesconf.org

Hal publie 2 principales plateformes : Episciences.org et Sciencesconf.org. Elle conserve actuellement 9 300 revues, 8 151 images, 3 421 de thèse et 3 103 Chapitre d’ouvrages. En tout 23 975 documents, dont 5 661 (24%) ont été déposés en 2018. Le nombre de 600 000 documents est dépassé depuis sa création. 11 529 de ces dépôts concernent des documents publiés en 2019 parmi lesquels 5 278 sont des articles (CCSD 2, 2019).

A travers ces deux plateformes, Hal conserve et publie 15 revues dont une Africaine : ARIMA. La revue Arima est créée des suites d’une collaboration scientifique Nord/Sud menée depuis plus d’une vingtaine d’années. L’initiative est arrivée au cours des activités de CARI (Colloque africain pour la Recherche en Informatique et mathématiques appliquées). Arima permet de publier les résultats de recherche issus de ces coopérations. Le domaine scientifique recouvre tous les sujets de recherche de l’informatique et des mathématiques appliquées (Hal, 2019). Que sont les plateformes Episciences.org et Sciencesconf.org ?

Episciences.org

Episciences.org héberge des revues en Open Access (épi-revues) et permet la soumission des articles par un dépôt dans une archive ouverte (Episciences 2, 2019). Episciences.org diffuse une bibliothèque numérique ELPUB (ELectronic PUBlishing). Elpub présente les résultats de recherches sur différents aspects de l’édition numérique sur le plan culturel, économique, social, technologique, juridique, etc. ces résultats impliquent une communauté internationale diversifiée de chercheurs œuvrant, entre autres, dans les domaines des sciences et des sciences humaines et sociales, des bibliothécaires, des éditeurs (ELPUB, 2019).

D’ailleurs, l’on trouve une publication intitulée : Global OA APCs (APC) 2010–2017: Major Trends (Morrison, 2019) de Heather Morrison, chercheuse principale de Sustaining knowledge common. Cette diversité d’acteurs montre la diversité des contributions pour Hal archive.

Cette possibilité de faire des dépôts dans Episciences.org est une avancée majeure des publications en français par rapport aux plateformes en anglais qui sont récentes. Kathleen Shearer, al. (2019) présentent dans une récente l’approche Pubfair. En matière de communication scientifique, l’approche facilite le partage et la collaboration en ligne, tout en favorisant la transparence et la confiance dans les résultats de la recherche diffusés par le biais des services.

Pubfair est un cadre de publication ouvert qui permet la soumission, l’évaluation et à l’accès à une variété de résultats de recherche. Elle permet également aux utilisateurs de créer des canaux de diffusion pour divers groupes de parties prenantes (Kathleen Shearer, al., 2019, 6). Pour Heather Morrison, le cadre Pubfair est un excellent début pour une profonde transformation nécessaire dans la manière dont les universitaires travaillent ensemble et diffusent la recherche. C’est le type d’approche le plus susceptible de générer des économies importantes en fonction des dépenses actuelles consacrées à l’édition savante.

Sciencesconf.org.

Sciencesconf.org est une plateforme Web qui s’adresse aux organisateurs de colloques, ou réunions scientifiques. Elle facilite les différentes étapes du déroulement des conférences depuis la réception des communications jusqu’à l’édition des actes en passant par la relecture et la programmation des thématiques (Episciences 2, (2019).

Tableau 1 : Principaux types de documents

Tableau 2 : Principaux types de documents

Conclusion

Hal est une archive ouverte qui conserve des documents d’images, de revues, de thèse, etc. Elle facilite l’organisation de conférences scientifiques. Une revue africaine (Arima) y figure parmi une quinzaine de revues.

Bibliographie

Arima, (2019). Présentation – Revue africaine de la recherche en informatique et mathématiques appliquées. https://arima.episciences.org/

Centre pour la Communication Scientifique Directe, 2019 -2, Dépôts dans HAL : 600 000 ! https://www.ccsd.cnrs.fr/2019/07/depots-dans-hal-600-000/

Centre pour la Communication Scientifique Directe, 2019-1, Epi-revues

https://www.ccsd.cnrs.fr/epi-revues/

ELPUB, (2019). ELPUB Digital Library. https://elpub.architexturez.net/

Episciences 1, (2019) Documentation. À propos. https://doc.episciences.org/a-propos/

Episciences 2, (2019). Plateforme de gestion de congrès scientifiques.

https://www.sciencesconf.org/

Hal, (2019). Archive ouverte en Sciences de l’Homme et de la Société. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/

Morrison, H. (2019). Global OA APCs (APC) 2010–2017: Major Trends

https://elpub.architexturez.net/

Morrison, H. (2019). Peer review of Pubfair framework.

https://wordpress.com/view/sustainingknowledgecommons.org

Shearer, K., Ross-Hellauer, T., Fecher, B., et Eloy, R. (2019). Pubfair A Framework for

Sustainable, Distributed, Open Science Publishing Services.

https://comments.coar-repositories.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/09/Pubfair_-A-Framework-for-Sustainable-Distributed-Open-Science-Publishing-Services.pdf

TiK ToK: Post-Crash Party Pop, Compulsory Presentism and the 2008 Financial Collapse

As pundits increasingly speculate about the likelihood and character of another recession, I’m thinking about the one from which we’re still recovering. Specifically, I’m thinking about a certain strain of American pop music—or a certain sentiment within pop music—that it seems to me accelerated and concentrated just after the 2008 financial collapse. This strain, which obviously co-existed with many other developments in popular music at the time, takes party songs and adds to them two interconnected narrative elements: on the one hand, partying is cranked up, escalated in one or multiple ways, moving the music beyond a party anthem and into something new. On the other hand, the rationale for such a move consistently derives from an attitude of compulsory presentism, in which the future is characterized as unknown, irrelevant, or is otherwise disavowed.

In the American context, the popular (and, I argue, misguided) take on the music of the great recession is that we didn’t have any—in other words, because no one was directly singing about the crisis, there was no music that responded to it. But this is an extremely limited way of understanding how music and socio-political life interact. In this post, I consider specifically American notions of mainstream party culture to argue that the strain of party music described above and below is the music of the crash, not because it literally speaks about it but because it reflects a certain attitude expressed and experienced by those at the front of both popular music listening at the time and the collapse itself: the graduating classes of 2008-2012.

By “party music” I do not mean (exclusively) music to which people party; rather, I am trying to trace what happens to music that is about partying during the crash. When I say that these songs transform from being party anthems into “something new,” what I mean is that in their extremeness, both the represented parties and the organizing affect of these parties reflect an urgency, a crisis, or a lack of choice condition. In short, what I’m calling “Post-Crash Party Music” (PCPP) responds to the 2008 financial collapse and the broader context of climate devastation by instituting a compulsory presentism that manifests through a frenetic, extreme, nihilistic celebration, a never-ending party that is also the last party (before the end of the world).

I’ll briefly mention two prime examples, both from what might be the peak year of this trend, 2010. First, Ke$ha’s single “(and #1 on Billboard’s Year-end Hot 100), “TiK ToK” sees Ke$ha brushing her teeth with a bottle of whiskey, while the last line in the chorus reveals why this is happening: Ke$ha sings, “The party don’t stop, no,” implying that the song’s narration picks up in a moment that could be any moment, an eternal present that is non-distinguishable from any other moment.

This line captures both of the defining characteristics of PCPP: 1) the party is extreme because 2) it never ends, or is always presently occurring. Although there are multiple ways of creating the eternal present that the party represents, each song in this category is invested in denying both past and future in a way that makes the presentist attitude of the partygoers a mandatory condition. This requirement is what makes PCPP more extreme, narratively, than party pop of previous eras.

As a second example, take The Black Eyed Peas’ quintessential party anthem “I Gotta Feeling.” Throughout most of the song, listeners are set up to experience what sounds like a fairly typical party jam: although the Black Eyed Peas render this joyous, optimistic track as perhaps more formally ‘perfect’ or effective than many of its competitors, it still follows a standard EDM format and a fairly conventional sentiment.

However, near the end of the track, as if responding to the pop-culture/post-crash landscape by afterthought, the Black Eyed Peas very casually disclose that the night that has all along been referenced as “tonight” is in fact every night: “Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday/Friday, Saturday, Saturday to Sunday/Get, get, get, get, get with us, you know what we say, say/Party every day, p-p-p/Party every day, p-p-p [repeat 10x]…”

Party anthems of one kind or another have been with us for a long time. But I would argue that something else is going on here. The traditional ambition to party until the sun comes up or to party all night has been eclipsed by a more extreme goal, which is to never stop partying at all. In this new space, the time of day or the day of the week is irrelevant; time itself evaporates in the indistinguishable space of an everlasting present.

My argument here is that this music–specifically in its insistence on a party’s ceaselessness–represents almost the complete opposite of its expressed sentiments: that is, rather than rapturous or celebratory moods, PCPP reflects widespread existential and economic anxiety that is shared among the entire millennial generation, but which was acutely present for the classes that graduated college between 2008 and 2012. Its insistence on partying forever is indicative of this generation’s awareness that the future is bleak.

Economically, we know that this cohort will live with repercussions of the financial collapse for the rest of their lives. (See for instance: “Bad News for the Class of 2008”; “This Is What the Recession Did to Millennials”; “A Decade Later Many college grads from the Great Recession are still trying to catch up”; “2008 was a terrible year to graduate college”; “2008: Ten Years After the Crash, We Are Still Living in the World It Brutally Remade”; and the pithily-titled but quite thorough “Millennials are Screwed”.) Existentially, while the millennials were not the first to cognize and politically articulate the stakes of the unfolding climate crisis, they are, as a “young generation,” perhaps the first identifiable group who will most certainly face its longterm consequences. Rather than simply distract us from these realities, PCPP is predicated on our understanding of those realities. In the face of these circumstances and more, is it any wonder that the affective (if not conscious) response was to live it up while there was still time?

I am not arguing that PCPP harbors any ambitions to address any such anxieties; on the contrary, this music is, on its face, also an example of the much broader genre of neoliberal corporate pop music, a commodity that aims to utilize listener sentiments to maximize profit. That is why PCPP cuts across or includes such racial and gender diversity in its performers, and why it also corresponds to broader trends in pop that elevate and glamorize conspicuous, over-the-top consumption, the kinds of caricatured displays of spending-power that are hallmarks of PCPP as well as other mainstream genres. The discourse of an endless party is also a really good one in which to promote consumption―especially consumption that is taken to the extreme, or is justified through the logic of embracing “life” while we can.

No, from the perspective of the music industry, this music is not about anxiety but is, like all corporate music, still about including as many listener-customers as possible in the cross-branded spectacle of neoliberal pop. Instead, my claim is that this music, however inadvertently, resonates with listeners in a particular, affective way, and in the encounter between neoliberal pop music and a group of anxious American listeners, an accelerated sentiment emerges and spins itself out. We are still consuming, but endlessly so; and that very ceaselessness speaks to a deeper existential dread at the heart of our voracious appetites.

Emerging from this resonance between extreme party music and extreme anxiety are several traceable tropes, each expressing the ambition to party forever. For instance, the “don’t stop” imperative is often paired with the seemingly paradoxical sentiment that “we only have tonight”; but insofar as the end of that night heralds a return to reality (the post-crash landscape) one solution is to simply refuse to stop the party. In this way, the night can “last forever” within the space of the music. Taken together, the PCPP ethos can be summarized by the phrase, as a colleague recently put it, “right now forever.”

There is a specific construction at work here that allows PCPP to impose its presentist timespace: the forever-now is not extended out of joy, but rather out of necessity. By acknowledging that our time (out there) is limited, it constructs a space (in here) that resists normative flows of temporality. PCPP simply disallows temporality into its consciousness–it refuses to acknowledge the existence of a past and especially not a future. Here the “compulsory” element of its presentism emerges: it is compulsory both because within the affective space of the music, the rules do not allow temporality to exist, and because, when our futures have been irrevocably damaged, the present is, in effect, all that we will be allowed to experience.

There are many more examples from this period, all riffing on the same nihilistic affect: “Tomorrow doesn’t matter when you’re moving your feet” (Pixie Lott, “All About Tonight”); “This is how we live/every single night/take that bottle to the head and let me see you fly” (Far East Movement, “Like a G6”, 2010); “Still feelin’ myself I’m like outta control/Can’t stop now more shots let’s go” (Flo Rida, “Club Can’t Handle Me”, 2010). In this context, assurances from Lady Gaga that “It’s gonna be ok” if we “Just Dance” seem less hopeful and more ironic, as if born from denial.

Surely, some of these songs take up the “don’t stop” imperative simply by virtue of its ubiquitous circulation through a pop-culture economy (Junior Senior’s 2003 “Move Your Feet” comes to mind here). I am not arguing that any song that expresses such a generic utterance be considered a part of this post-crash formation; what it takes to qualify, it seems to me, is a distortion whereby the generic affect is pumped so full that it breaks something, a process that sometimes introduces a dark subtext into the music, but which no matter what displays elements of excess that go beyond the pale of a celebratory dance tune. Eddie Murphy’s “girl” wants to “Party All the Time”, but this alone doesn’t qualify the tune as an anxiety anthem because it is a source of hurt and stress for the speaker’s character—ceaseless partying here is sublimated into a narrative about a certain romantic relationship. What distinguishes PCPP, on the other hand, is the sense (however vague) that the “don’t stop” imperative is urgent, and meant to protect us from the world that is waiting outside the club.

PCPP differs in this way from other genres that consciously articulate a dissatisfaction (of whatever kind) with contemporary conditions. The millennial nihilism of an everlasting party is not the same as Gen X’s cynical malaise, which had more to do with resistance to meaningless corporate employment than it did the prospects of no employment at all. PCPP is not punk-rock anarchism nor grunge’s serious grappling with the consequences of capitalism on people’s mental health. PCPP is purely affective, a manic/cathartic punishment-therapy that does not need to denotatively speak of what’s happening in the world because that world is always already experienced in an extreme way. PCPP responds by dialing up the party to a degree of fervor that is correspondingly intense, able to drown out the noise, and it achieves this effect by turning parties into a paradox that is both time-limited and never-ending.

It is true that I have mostly focused on lyrics in this argument. But first of all, other factors also contribute to the sense of PCPP as existential: see for instance the music video for Britney Spears’ “Till the World Ends” (2011), which literalizes the argument I’m making by representing people dancing as the planet crumbles. Likewise, the music video for LMFAO’s “Party Rock Anthem” (2011) casts the band’s beat as a contagion that has afflicted the “whole world,” compelling them to dance ceaselessly in a way that resonates appropriately with post-apocalyptic genres.

Second of all, the “music itself” never exists in isolation from the lyrics or indeed from any other element of a tune. What I would argue that the sounds and formal elements of these songs contributes to the PCPP ethos is a sense of tension and paradox: namely, the paradox between the stated dream of an unending party, and the reality that underlies said dream. It is, physically and otherwise, impossible to keep dancing indefinitely, a fact reflected in the form of this music, which still follows EDM rules of build-up and release, those forms that give one’s body time to rest and appropriate places to feel the natural climax of a song. The tension between the music (which corresponds to the body) and the lyrics (which aim into the afterlife) is the central contradiction that makes PCPP so e/affective.

Thus, the PCPP genre or sentiment, which flashes brightly from 2009-2012, meets its death in and through the track that most comprehensively embodies it: Miley Cyrus’s “We Can’t Stop” (2013). In this deeply melancholic hit, PCPP is followed to its logical conclusion: those who at first refused to stop partying are now entirely incapable of doing so even if they wanted. This is the most extreme version of the PCPP worldview, so extreme that it spread into the music, inverting the entire affect from pumped-up party jam to down-tempo lament, a lament with almost no temporality even in its form.

Although my reading of “We Can’t Stop” differs from Robin James’s, her description perfectly captures the way that song’s form finally achieves the same presentism that PCPP’s lyrics always established, a closed world of “now”. In her 2015 book Resilience and Melancholy, James writes,

Just as the lyrics suggest that the ‘we’ is caught in a feedback loop it can’t stop, the music keeps spuriously cycling through verses and choruses without moving forward or backward…In other words, time isn’t a line, it’s Zeno’s paradox; not a pro- or re-gress but involution (177-178).

If anything, this formal stagnation or inverted affect brings “We Can’t Stop” into the space of the trap music it plays at, and constitutes one of the many ways in which the song cannot sustain its contradictions. As Kemi Adeyemi makes clear, trap music certainly has to do with partying; but its intersections with neoliberal capitalism are particular to Black lives in a way that is wholly different from Cyrus’ attempted deployment. Thus, reaching to trap for a PCPP affect has the devastating effect of exploding the entire sentiment.

In other words, “We Can’t Stop” exposes all the lies that PCPP, in its heyday, furthered: the idea that the party could continue indefinitely, and (by extension) so too could the “fairy tales of eternal economic growth” and the supposed post-racial utopia opened up by neoliberal capitalism. “We Can’t Stop” gives sound to these fictions, through its own form and in various ways: from its well-documented appropriation of Black culture, to the untenable contradiction at the heart of its sentiments. “We can do what we want” but we also “can’t stop.”

Rather than hearing this tune as “painfully dull” (180), this song has always been morbidly fascinating to me, a bleak statement about our inability to move past the moment in which we’re caught. In other words, our presentism is now also compulsory because we’ve gotten so used to it that we can no longer imagine a future at all, or at least not one in which catastrophe doesn’t occur; nor can we imagine the solutions that would help us when it does. Instead, we have the iPhone 11 and self-driving cars. Instead, we have an inverted yield curve and predictions of another (perpetually recurring) market crisis. Instead, we have billionaires doubling down, grabbing every last resource they can from the planet in order to insulate themselves from the effects they have created, a final and pathological shopping spree. Seen from that perspective, while it marked the end of PCPP as a trend, “We Can’t Stop” remains striking as both indictment and prophecy.

—

Featured Image: Culture Project 1: Ke$ha by Flickr User HyundaiCardWeb (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

—

Dan DiPiero is a musician and Visiting Assistant Professor of American Studies at Miami University of Ohio, where he teaches American popular culture and music history. His current book project investigates the relationship between improvisation in music and in everyday life through a series of nested comparisons, including case studies on the music of Eric Dolphy, John Cage, and contemporary Norwegian free improvisers, Mr. K. His work has appeared in Critical Studies in Improvisation/Études critiques en improvisation, the collection Rancière and Music (forthcoming, Edinburgh University Press), and boundary 2 online. He plays the drums.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

In Search of Politics Itself, or What We Mean When We Say Music (and Music Writing) is “Too Political”–Elizabeth Newton

Poptimism and Popular Feminism–Robin James

Benefit Concerts and the Sound of Self-Care in Pop Music–Justin Adams Burton

Straight Leanin’: Sounding Black Life at the Intersection of Hip-hop and Big Pharma–Kemi Adeyemi