If you could listen to your DNA, what would it sound like? A few answers, at random: In 1986, the biologist and amateur musician Susumo Ohno assigned pitches to the nucleotides that make up the DNA sequence of the protein immunoglobulin, and played them in order. The gene, to his surprise, sounded like Chopin.

With the advent of personalized DNA sequencing, a British composition studio will do one better, offering a bespoke three-minute suite based on your DNA’s unique signature, recorded by professional soloists—for a 300GBP basic package; or 399GBP for a full orchestral arrangement.

But the most recent answer to this question comes from the genealogy website Ancestry.com, which in Fall 2018 partnered with Spotify to offer personalized playlists built from your DNA’s regional makeup. For a comparatively meager $99 (and a small bottle’s worth of saliva) you can now not only know your heritage, but, in the words of Ancestry executive Vineet Mehra, “experience” it. Music becomes you, and through music, you can become yourself.

screencap by SO! ed JS

As someone who researches for a living the history of connections between music and genetics I am perhaps not the target audience for this collaboration. My instinct is to look past the ways it might seem innocuous, or even comical—especially when cast against the troubling history of the use of music in the rhetoric of American eugenics, and the darker ways that the specter of debunked race science has recently returned to influence our contemporary politics.

During the launch window of the Spotify collaboration, the purchase of a DNA kit was not required, so in the spirit of due diligence I handed over to Spotify what I know of my background: English, Scottish, a little Swedish, a color chart of whites of various shade. (This trial period has since ended, so I have not been able to replicate these results—however, some sample “regional” playlists can be found on the collaboration homepage).

screen capture by SO! editor JLS

While I mentally prepared myself to experience the sounds of my own extreme whiteness, Ancestry and Spotify avoid the trap of overtly racialized categories. In my playlist, Grime artist Wiley is accorded the same Englishness as the Cure. And ‘Scottish-Irish’, still often a lazy shorthand for ‘White’, boasted more artists of color than any other category. Following how the genetic tests themselves work, geography, rather than ethnicity, guides the algorithm’s hand.

As might be expected, the playlists lean toward Spotify’s most popular sounds: “song machine” pop, and hip-hop. But in smaller regions with less music in Spotify’s catalog, the results were more eclectic—one of the few entries of Swedish music in my playlist was an album of Duke Ellington covers from a Stockholm-based big band, hardly a Swedish “national sound.” Instead, the music’s national identity is located outside of the sounding object, in the information surrounding it, namely the location tag associated with the recording. In other words: this is a nationalism of metadata.

One of the common responses to the Ancestry-Spotify partnership was, as, succinctly expressed by Sarah Zhang at The Atlantic: ‘Your DNA is not your culture’. But because of the muting of musical sound in favor of metadata, we might go further: in Spotify’s catalog, your culture is not even your culture. The collaboration works because of two abstractions—the first, from DNA, to a statistical expression of probable geographic origin; and second from musical sound and style characteristics, to metadata tags for a particular artist’s location. In both of these moves, traditional sites of social meaning—sounding music, and regional or familial cultural practice—are vacated.

Synthetic Memetic / Matthew Gardiner (AU): Gardiner composed a DNA sequence in such a way that the series of nucleotide bases in it correspond to the letters of the song title “Never Gonna Give You Up” by Rick Astley, and then integrated them symbolically into a pistol. Credit: Sergio Redruello / LABoral Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

There is a way in which this model could come across as subversive (which has not gone unnoticed by Ancestry’s advertising team). Hijacking the presumed whiteness of a Scotland or a Sweden to introduce new music by communities previously barred from the possibility of ‘Scotishness’ or ‘Swedishness’ could be a tremendously powerful way of building empathy. It could rebut the very possibility of an ethno-state. But the history of music and genetics suggests we might have less cause for optimism.

In the 1860s, Francis Galton, coiner of the word ‘eugenics’, turned to music to back up his nascent theory of ‘hereditary genius’—that artistic talent, alongside intelligence, madness, and other qualities were inherited, not acquired. In Galton’s view, musical ability was the surest proof that talents were inherited, not learned, for how else could child prodigies stir the soul in ways that seem beyond their years? The fact of music’s irreducibility, its romantic quality of transcendence, was for Galton what made it the surest form of scientific proof.

Galton’s ideas flourished in America in the first decades of the twentieth century. And while American eugenics is rightly remembered for its violence—from a sequence of forced sterilization laws beginning with Indiana in 1907, to ever-tightening restrictions on immigration, and scientific propaganda against “miscegenation” under Jim Crow—its impact was felt in every area of life, including music. The Eugenics Record Office, the country’s leading eugenic research institution, mounted multiple studies on the inheritance of musical talent, following Galton’s idea that musical ability offered an especially persuasive test-case for the broader theory of heritability. For 10 years the Eastman School of Music experimented on its newly admitted students using a newly-developed kind of “musical IQ test”, psychologist Carl Seashore’s “Measures of Musical Talent”, and Seashore himself presented results from his tests at the Second International Congress of Eugenics in New York in 1923, the largest gathering of the global eugenics movement ever to take place. His conclusion: that musical ability was innate and inherited—and if this was true for music, why not for criminality, or degeneracy, or any other social ill?

From “The Measurement of Musical Talent,” Carl E. Seashore, The Musical Quarterly Vol. 1, No. 1 (Jan., 1915), p. 125.

Next to the tragedy of the early twentieth century, Spotify and Ancestry teaming up seems more like a farce. But scientific racism is making a comeback. Bell Curve author Charles Murray’s career is enjoying a second wind. Border patrol agents hunt “fraudulent families” based on DNA swabs, and the FBI searches consumer DNA databases without customer’s knowledge. ‘Unite the Right’ rally organizer Jason Kessler ranked races by IQ, live on NPR.. And, while Ancestry sells itself on liberal values, many white supremacists have gone after ‘scientific’ confirmation for their sense of superiority, and consumer DNA testing has given them the answers they sought (though, often, not the answers they wanted.)

As consumer genetics gives new life to the assumptions of an earlier era of race science, the Spotify-Ancestry collaboration is at once a silly marketing trick, and a tie, whether witting or unwitting, to centuries of hereditarian thought. It reminds us that, where musical eugenics afforded a legitimizing glow to the violence of forced sterilization, the Immigration Acts, and Jim Crow, Spotify and Ancestry can be seen as sweeteners to modern-day race science: to DNA tests at the border, to algorithmic policing, and to “race realists” in political office. That the appeal of these abstractions—from music to metadata, from culture to geography, from human beings to genetic material—is also their danger. And finally, that if we really want to hear our heritage, listening, rather than spitting in a bottle, might be the best place to start.

—

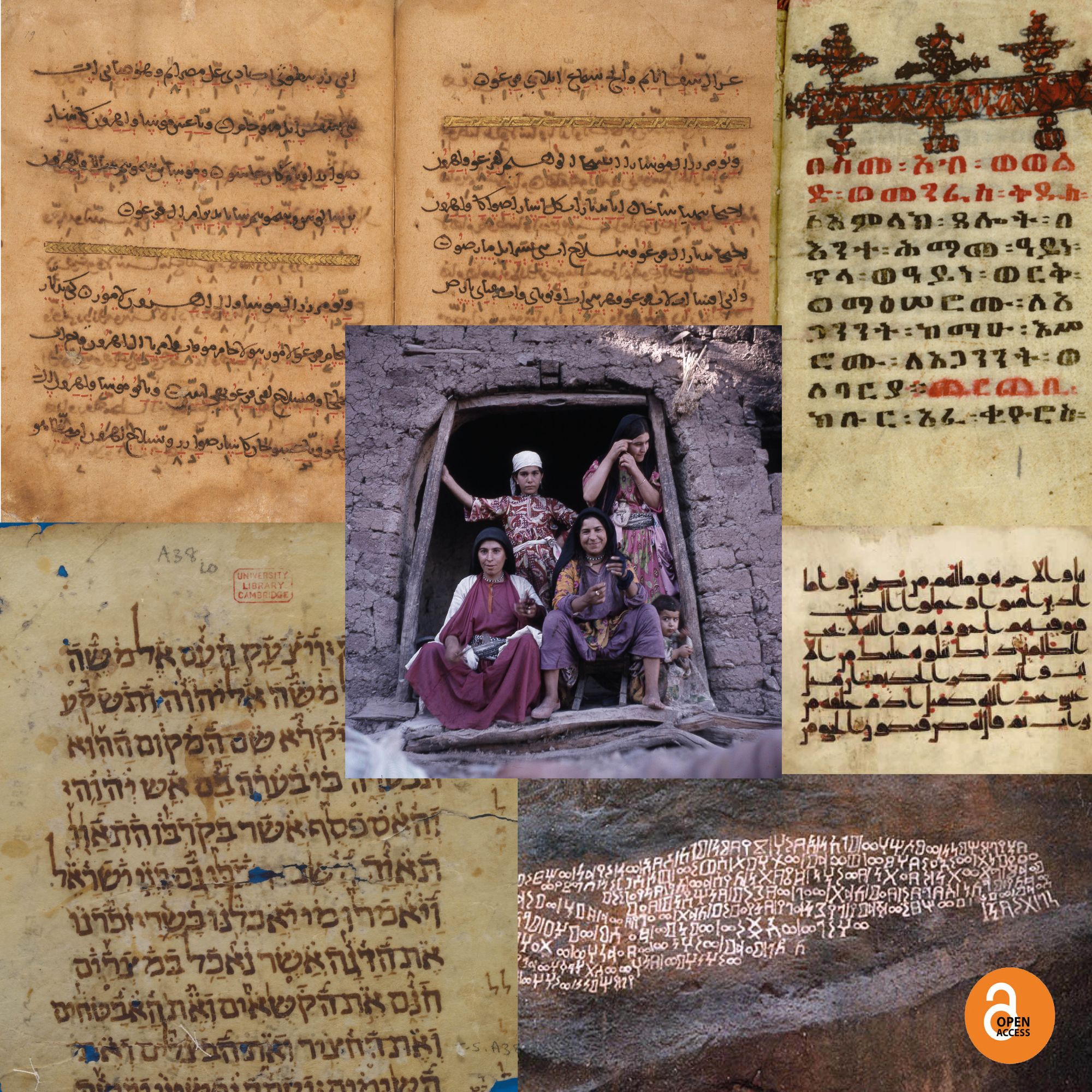

Featured Image: “DNA MUSIC” Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

—

Alexander Cowan is a PhD candidate in Historical Musicology at Harvard University. He holds an MMus from King’s College, London, and a BA in Music from the University of Oxford. His dissertation, “Unsound: A Cultural History of Music and Eugenics,” explores how ideas about music and musicality were weaponized in British and US-American eugenics movements in the first half of the twentieth century, and how ideas from this period survive in both modern music science, and the rhetoric of the contemporary far right.

—

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

Hearing Eugenics–Vibrant Lives

In Search of Politics Itself, or What We Mean When We Say Music (and Music Writing) is “Too Political”–Elizabeth Newton

Poptimism and Popular Feminism–Robin James

Straight Leanin’: Sounding Black Life at the Intersection of Hip-hop and Big Pharma–Kemi Adeyemi

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig:

REWIND! . . .If you liked this post, you may also dig: