Episode 1 with introduction: https://networkcultures.org/blog/2020/04/09/selfies-under-quarantine/

Episode 2: STORYTELLING OR ‘STORIES’?

In collaboration with Danielle, Shaina, Briana, Jackie, Marta, Gabriella, Sydney, Elena, Sophia and Natalia

This week’s readings:

Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov’ and his short story The Handkerchief. Maisa Imamovic, ‘Aesthetics of Boredom in Times of Corona’. We watched Jenny Odell’s talk on ‘How to Do Nothing’.

I thought about Samuel Beckett’s ‘Waiting for Godot’. Three quotes:

‘We wait. We are bored. No, don’t protest, we are bored to death, there’s no denying it. Good. A diversion comes along and what do we do? We let it go to waste.’

‘The tears of the world are a constant quantity. For each one who begins to weep somewhere else another stops. The same is true of the laugh. Let us not then speak ill of our generation, it is not any unhappier than its predecessors. Let us not speak well of it either. Let us not speak of it at all. It is true the population has increased.’

‘Tomorrow when I wake or think I do, what shall I say of today? That with Estragon my friend, at this place, until the fall of night, I waited for Godot?’

INSTA VS. BENJAMIN

As last week we approached ‘boredom’, this time I feel I need to talk about Walter Benjamin’ and his ‘storyteller’.

Let’s forget about Nikolai Leskov and reflect about storytelling and the art of Instagram stories instead, I propose.

Natalia thinks that ‘storytelling is about having something to say that is of intangible nature and value. The story of experience is intangible’. So, ‘can storytelling happen face-to-face? Yes. Can it happen online? I think no’, is her ultimate answer.

Gabriella is also skeptical about how the two things could eventually match. ‘Anyone can create Instagram stories… Storytelling used to be an art made by those who had a talent, now stories via Instagram are all inclusive and people with no talent at all can participate and create their own story’.

And yet there is something that gets irremediably lost with storytelling long before ‘Insta’ and the social media speed, Benjamin points out. Before our obsessive culture of the snap takes off, something happens already with the rise of the novel at the beginning of modern times. Printing deprives us of a certain pace, that of the epic, the familiar, the ‘told’, and replaces it with the novel, the fresh, the exceptional, the contemporary, the unfolding.

Briana writes: ‘No wonder why Benjamin opposes the “novel” to storytelling: the word novel, in fact, derives from the latin adjective “novus” which means “new”. The entry of the novel into modernity therefore seems to be following the increasing speed of life, and to satisfy our induced hunger for immediacy’.

The space of creation becomes a space of production, a functional space made by page numbers, bibliographies, printed copies, shelves to be filled, books to be sold. The space of creation turns into a space of solitary confinement, where the writer thinks in isolation and in function of, while no longer telling stories from experience, whether his own or others’.

This ‘social distancing’ ante litteram sells copies and creates reputations, yet it deprives from the gift of wisdom, empathy, connection.

Experience muted, collectivity erased, words eventually sink into the abyss of information, a mere collection of data that does not survive the ephemeral moment in which it was ‘new’.

Caption: newyorkercartoons A cartoon by @rozchast, from 2010

‘This whole issue’, Briana points out, ‘made me think about the structure of the ancient Greek square (the Agorà) versus the structure of what we think are our new squares, social media. What I found out is that the physical space of the Agorà, with its circular structure, conveyed and promoted inclusion (and therefore collectivity): the circle itself is a way to embrace and represent the democratic ideal of equality, supported by the circle’s definition being “a continuous curved line which points are always the same distance away from a fixed central point”. Social media’s structure, instead, is designed to place those who are more interconnected in the center and those who are less interconnected at the periphery, which Maisa Imamovic refers to when stating that “digital reality became knowledge competition […] for the sake of strengthening our online reputation in the eyes of the beholder”.

In fact, what we try to do on social media is to be more and more interconnected, trying to reach the center of the network, which we can visually picture by looking at this image:

The goal to enrich one’s online self is bigger than the goal to enrich any hypothetical discussion. People are not trying to build a community because in the first place they are not enabled by the structure; in the second place, because of the structure, the main goal is not to be all on the same level, but to get to the core of the network, enriching the online self by interacting as much as possible’.

Sophia’s words below echo Briana’s last point about capitalizing on the networks’ structure in order to create a brand, a social reputation, more followers. Even in times of crisis. Or, better said, especially in times of crisis.

‘I have noticed that YouTubers in general and other content creators have been publishing more than usual. Sure, it could be because of the excess amount of time they have on their hands, or it could be because they are trying to capitalize on all the clicks and views they can coax out of their followers during this time when everyone is on lockdown. It almost feels as though the content creators are preying on our boredom and giving us below standard content, whether it be video or blog posts, because they know we will click no matter what at this point’.

Shaina agrees that ‘social media influencers are really taking off during this time. A lot of people with a strong social media following who have a talent, a business, something worth value, that they can share with the world have seemed to really capitalize on these circumstances’.

Yet she does not think that this happens just because of the attention economy upon which social media influencers earn money and reputations. ‘I am honestly thankful for influencers like these because they have kept me busy and entertained during this time. I have hopped on the bandwagon for Chloe Ting’s 2 week summer shred, I keep up with Tasty for new, creative recipes that I cook with my family. It is people like this who are keeping me active during this period’, she concludes.

Danielle shows examples of ‘how a fitness influencer and a streaming service are continuing to advertise and grow business during this time’:

‘People capitalizing on the quarantine: the ads being pushed on Instagram have been interesting, a ton of workout and fitness supplement companies have been pushing content. Work on your summer body during this quarantine, you finally have the time.

I have also noticed a lot of streaming services have been pushing their services as you have the time to binge now.

I think this attitude of continuous productivity is detrimental to the empathy and processing that should be occurring during this time…Nurses are enduring 12 hour shifts day after day watching their patience die before them (video). I feel ashamed to be part of a culture that ignores the pain and trauma others are enduring’.

‘WHAT ARE YOU DOING’ IS THE NEW ‘HOW ARE YOU’

Maisa Imamovic: ‘By now almost nothing that happens benefits storytelling; almost everything benefits information’, Benjamin prophetically writes. You can picture him being ‘here’ with us, patting on the shoulder of someone like you experiencing severe FOMOI symptoms, the new syndrome of a crisis time, aka FEAR OF MISSING OUT ON THE INFORMATION….WFOR (whether fake or real).

Gabriella has experienced FOMOI: ‘especially this week I have been offline. I have stoped looking at Twitter that often, I have ignored social media a little and every night I feel I missed valuable information… Even if we go offline especially during this time I feel there is more anxiety of not knowing what is happening than while we are online’.

But is it really information that we are missing? And what’s the value of information that is injected in the data stream non-stop?

Natalia has a name for it: ‘the infrastructure of doing’. ‘Facebook never asks you ‘what are you thinking now.’ It is always about doing, performing an action, producing or consuming something, seeing or participating in the event that is unfolding in the never-ending loop of commodified entertainment. Boredom is no fun. Even if it were, it would be tricky to commodify on a mass scale. Boredom is no fun for our commercialized day-to-day reality because its essence is inherently individual and fluid, and it is tied to what it unsellable. Or one is tempted to say so. If on social media, we are constantly doing something, or at least we are partly occupied with performing an action that requires our attention, there is no place boredom to creep in’.

Gabriella adds: ‘These are examples of how the speed of media never ends. If there is boredom them social media make sure to deal with your boredom and find ways to entertain you, just like the TikTok links below. How can we get bored if circulation and speed are faster than ever?’

https://www.tiktok.com/@mtvuk/video/6810766824196672773

https://www.tiktok.com/@jamiefreestyle/video/6811146201950440710

And Danielle concludes: ‘don’t know if I am the only one, but I don’t feel bored. I feel the opposite. Overstimulated. Sounds weird huh? A time where you have nothing to do than sit around your house… how are you not bored? I have never been in this much contact in my life. My email is flooded with long winded explanations. I receive paragraphs on text daily. Phone calls everyday. I am hearing from people I haven’t spoken to in years. It’s almost overwhelming.

How can you not be entertained. We have every kind of technology. Between my family of 4, the internet, tv shows, card games, board games, working out, self-care, music, and work I feel like I am in overdrive. Constantly expected to be doing something, because “what are you doing” has become the new “how are you doing”.

Without structure, there is no separation between work and home. No lunch hour, no commuting times, just a constant flow of looming anxiety to be doing something’.

source: https://tapas.io/episode/1709280

EVERYTHING’S FINE, NO NEED TO PANIC

Space is collapsing. Benjamin’s novelist was writing in isolation and solitude. In quarantine, we no longer know the difference between where we live and where we work. The work space has invaded our living space, has eaten it up, leaving so little room to non-productivity. Everything should be made productive and functional. Everything should be given a name and ordered into a routine sequence of ‘to do’s, now more than ever.

We cannot afford the luxury of confusion and chaos inside, now that confusion and chaos reign outside. We are not allowed to panic.

source: https://tapas.io/episode/1687477

Natalia also talks about panicking in connection to what her home country, Poland, is implementing to fight Covid 19.

‘If I were to come to go back home tomorrow, I would become a subject to a self-Selfie-invigilation. As everyone who comes back from abroad, I would need to stay home for 14 days, and prove my self-isolation/quarantine by taking selfies whenever a special app tells me too. “People in quarantine have a choice: either receive unexpected visits from the police, or download this app,” said Karol Manys, Digital Ministry spokesman, as cited in cbsnews (yes, we do have “Digital Ministry.” How fancy isn’t it?). I would need to download an app, and then have 20 minutes to take a selfie each time after I receive an SMS/App notification to do so. Otherwise, police might come to check up if I am not breaking the rules of quarantine.

I wonder, why would they need my selfies if the app already has a geolocation system. The app itself is not groundbreaking. More advanced apps have been already launched in Singapore and South Korea, where they are able to track what people one is physically contacting and from what distance, and also making sure that people on quarantine don’t break the rules. In UAE, one has to fill in a permit to leave a house that is digitally glued to the user’s phone, checking the GPS location and duration of being outside. Why would I have to take selfies?

Because it’s also about fancy-sounding facial recognition technology, and that’s what sounds to me too much like Chinese social security plan.

The app gives the possibility to request medical aid or any kind of assistance, food delivery of psychological consultation etc., which is quite nice. What is not nice is that it is not clear how the app actually works, there is no source code accessible, its company apparently “does not sell the app to track consumer behaviors, as the app is only used to analyze the consumer environment and its basic focus is of interior usage in businesses and institutions.” The app also seems to be far from perfect, as hundreds of users reported errors in its GPS-location technology and the selfie-notifications. The app is active for 14 days, but the collected data (including the questionable amount of my selfies used for facial recognition) are kept for six years by several institutions and the company which created the app. Six years? Really? Like I wasn’t already objectified enough by having my representation scrambled and dismembered by all CCTV cameras, cookies, Facebook and Google and Amazon algorithms.

Maybe I am panicking too much, but there is something obnoxious about being ordered to take selfies.

Aren’t we all getting distracted from serious problems by weird apps, weirder news, new Instagram filters, new tik-tok videos, or by providing us with a media spectacle like super bowl (in the ‘past’ meaning before March 2020)?

Shouldn’t we all be really panicking?’.

BOREDOM IS LIKE YOUR MOTHER-IN-LAW

We are not allowed to panic, and we are not allowed to be bored in these confusing times.

Elena reminds us of Benjamin’s quote: “If sleep is the apogee of physical relaxation, boredom is the apogee of mental relaxation. Boredom is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience.”

She writes: ‘why do I hate boredom if it’s so beneficial? 1) Because complaining it’s the easiest thing to do; 2) Because the design of social media subconsciously (and mistakenly) taught me that I must avoid boredom; 3) Because I never considered the option of looking beyond the common consideration of boredom. I think that boredom is a tool only if we are aware of its potentiality, otherwise it’s just an empty, meaningless feeling. It’s the quality, not the quantity of events that makes boredom enjoyable. Boredom is a predominant aspect of our lives then we might as well learn to appreciate it. It is like your mother-in-law: if you get along with it/her your life is much easier. We can be “boredomphiles” or “boredomphobes”, it’s up to us.

From now on, I will embrace and exploit its benefits. To demonstrate my gratitude to Walter Benjamin for having opened my eyes…I wrote a boring poem born from boredom.

The ABC Of Boredom

Apparently, Boredom Creates Apathy. Be Cautious. All Blame, Complain About, Banish, Constantly Avoid Boredom. Change Attitude! Boredom Creates Abilities, Boosts Creativity ABottomless Chance. A Bonfire Can Awfully Burn Causing Agony, But Can Also Brighten, Creating Atmosphere. Boredom, Comparably, Ambiguous “Being”, Can Annoy But Can Also Be Celebrated. A Beneficial Calmness.

This writing style itself is a metaphor of boredom: although it feels limiting (as I had a limited choice of words) , it can be a tool for creativity’.

THE FINAL MATCH: INSTA VS BENJAMIN RELOADED

Here we come to the final match between Insta and Benjamin which has opened this week’s blog. Storytelling vs ‘stories’. Are the latter a modern version of Leskov? Or are they yet another dramatic evolutionary step -from the ‘novel’ to information down to the ‘story’- to finally dissolve storytelling into the ‘insta’ gratification of scrolling down, pretending to kill contemporary boredom while in the end generating more?

Shaina seems to agree that ‘Insta’ stories might be something of a different nature than ‘stories’. She writes: ‘An Instagram story is usually not entertaining to me. I click through them quickly to clear the notification, I am not really paying attention to the details, I have no connection to the story, I am uninterested really’.

Marta adds: ‘Honestly, people don’t even pay attention to Insta stories, especially videos…. they just tap tap tap until there’s nothing else to look at….. I know this because I do it myself…. Overall, a story has a structure and a couple of rules, whereas Instagram stories can be used for instant and short term gratification and to keep you from feeling too bored. For me, when I watch people’s “stories,” I don’t expect to either learn something or to remember any of it. It’s simply for rapid entertainment and usually have no emotional connection. Insta stories are a way to pass time and to cope with boredom even when there are other ways to do so’.

And Jackie has her own story on ‘stories’: ‘My sister is the producer of her own show on Instagram called irrelevant-stories-taken-when-she-walks-through-the-front-door-and-proclaims-her-activities-to-the-world, or as you all call “Instagram Stories”. These “stories” are so weird to me because Benjamin is right: stories are not meant to be sheer information, stories are not “Roman is having an okay day and bought a Coke-Zero” (hyperlink or embed the video in the post) yet Instagram brands otherwise with their Snapchat-copy-cat function.

So Benjamin and I are here, sitting in the corner, very confused at this choice method of hers to spend her time. This is no novelization of life that is being shared in these fifteen second clips, and no artistry that works to weave the senses. It’s, well, whatever it is, and the only one who wishes to call these stories is Instagram themselves’.

So, an Insta story is not about telling others a story. Mainly, it is about telling others about US, isn’t it?

Elena confesses: ‘I share Instagram stories with the hope of making people feel something…not because I want them to feel something…it’s more because I want them to produce more notifications I can look at. With storytelling, we used to be better listeners, we were poliedric, productive, creative and empathic. Now, with social media, we exploit other’s feelings for stickiness (hyperlink https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/networked-affect) while social media exploit us for immaterial labour. We feel puppeteer but we are puppets’.

Marta has a point: ‘The last thing about Benjamin that I found very interesting is when he says that “storytelling without community cannot exist because it’s a collective experience.” That’s because, if you think about it a story isn’t a story if it involves just one element or one person’.

And Natalia adds: ‘I fully agree with Benjamin on how storytelling is about exchanging experiences. It is not about me or you per se. It is about something that happened and how it unfolds between us. There is no experience in the Instagram “story.”

Instagram design turns the concept of the story on its head in that:

1) There is a time limit for the story to unfold (Instagram breaks down longer stories into chunks of material).

2) There is a time limit for the story to last (24h), therefore, there is a deadline for it to be relevant (24h).

3) The story can be brought up as a memory after one year only to disappear again.

4) Consequently, Instagram provides a story with material objectification, which turns a ‘story’ into a digital object of no meaning or belonging in space in time. A ‘story’ is suddenly a ‘memory,’ yet one can only revisit it after one year on the day it was posted. Since when memories can be accessed only in limited intervals of time?

5) Users (or ‘viewers’) are allowed to skip and go back to different parts of the story destroying its narrative value.

6) By lacking the importance of narrative and chronology, any deeper meaning gets lost.

7) As stories are immediately played one after another, there is no time for the user to comprehend the story. Instead, the user is flooded with digital content.

8) There is no usefulness in the stories, no moral, practical, or proverb-like sense’.

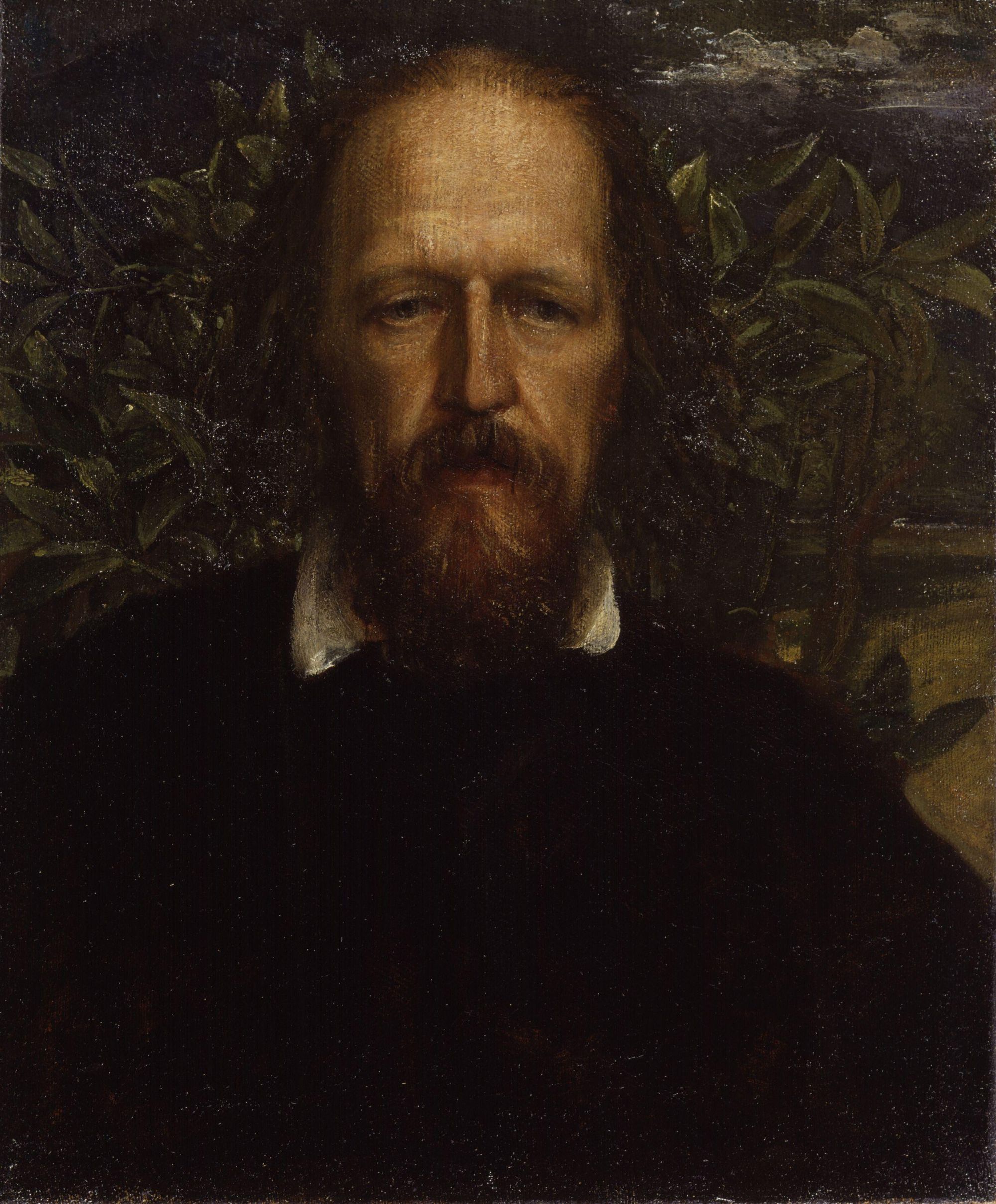

As Natalia says, there is something about narrative and chronology, about the intertwinement of them. In ‘Little History of Photography’ Benjamin observes that the length of time the subject had to remain still determines the special character of early photography, ‘a more vivid and lasting impression on the beholder’. Because of the technical limitations at the time, obliging to a long duration of the exposure, the subject of a picture had to grow ‘into the picture’ and live its ‘way into’ it. This would pave the way to what he calls ‘the optical subconscious’, a sort of Vertovian kino-eye. The mechanical gaze, the way in which the technological apparatus sees us and catches the ‘tiny spark of contingency, the here and now’ of the picture which the human eye cannot immediately grasp.

We search within the picture to find the ‘inconspicuous place’ where, Benjamin says, ‘future nests still today – and so eloquently that we, looking back, may rediscover it’.

It might be a gloomy future hidden in the past, as in Dauthendey’s photo that Benjamin shows us, picturing his fiancée who, many years later, will be found in their Moscow apartment with her veins slashed. ‘Her gazes passes him by, absorbed in an ominous distance’. The optical unconscious catches and fixes in the eternal moment of the picture what her gaze unveils to the mechanical eye only.

Where is the optical unconscious today? Does it still exist? Can we still learn about it through photography, looking into our past so to learn about our future? Is the culture of the snap able to produce something as mysteriously magical as the long exposure did?

The snaps, lenses, filters seem to look for “interesting juxtapositions” rather than digging in the depth on the picture. And as the camera gets smaller and smaller, ‘ever readier to capture fleeting and secret images whose shock effect paralyzes the associative mechanisms in the beholder’, the ‘inscription must come into play, by means of which photography intervenes as the literarization of all the conditions of life, and without which all photographic construction must remain arrested in the approximate’.

As usual, Benjamin has an astonishing intuition, a flash-flash-forward that takes us directly into today’s culture of captions and hashtags, all those little signs contributing to a consolidation of the textual self. At the time, he called it ‘the literalization of all the conditions of life’. It’s pretty much what it’s happening now with Whatsapp, Instagram, Snapchat, etc.

All aspects of life (from eating to having sex), all conditions of life (feeling angry, bored, happy), have to be rendered into textual elements that are searchable, quantifiable, sellable. Everything has to be rendered into a text, no matter what text. Whatever text. The self has to be rendered into a text, whether a meme, an emoji, a hashtag, an Instagram story.

We no longer tell stories, then.

‘Insta’ stories tell us. They tell who we are, what we will be.

Recently, Sydney’s grandmother has tested positive to Corona virus. Since then, Sydney has been thinking about the fact that she might succumb to it. She shares her thoughts with us:

‘I already have an Instagram post planned for her, which makes me sick to my stomach to think about. But this is how it relates to my classes’ discussion for this week. I don’t know how I’d talk about my grandma’s death, so I’d follow in my peers’ footsteps: make an Instagram post. I have the picture planned out. I have the caption roughly penner in my head. It would tell her story. How she almost became a nun, until she didn’t. How she was the only female-rifle shooter on her college campus. How she had 7 children, and lost one tragically. How she survived a stroke, dealing with it so well that doctors couldn’t even figure out what it was. How she can still sometimes remember who we are even with memory loss.

She’s asymptomatic, currently alive, and yet I have a ‘post’ planned out for her. It goes to show that social media is a collection of the largest events that occur in our lives; this would be the first major loss for me. It warrants an Instagram post rather than something placed on my stories. I don’t want it to disappear and be forgotten despite the possible pain that I will face in my future.

And that’s where my mind went when I found out my grandmother has COVID-19’.

WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF ‘NO ONE GIVES A SHIT’

As an ending note to this week’s blog, please ‘Welcome to the world of “No one gives a shit” by our Shaina.

Whenever I complain about something ridiculous my dad is always quick to humble me with, “Welcome to the world of no one gives a shit.” It is said out of love of course. What is meant by it is that life isn’t always fair and you will experience hardships but we are not entitled to anything, we should work hard to achieve what we want, appreciate what we have, and never expect anything from anybody else. This week in particular was filled with hardship and unfairness but nevertheless, we persevere. This is not written as a cry for sympathy but to give perspective, here is a breakdown of my week:

Monday April 6th: My mom is admitted to the ER for emergency surgery and diagnosed with cancer. The doctor broke the news to her but she didn’t remember because she was still heavily sedated from surgery. The doctor called my dad, who was home because he cannot be in the hospital beside my mom due to COVID-19 visitor restrictions, to share the news.

Tuesday April 7th: 3 years to date since my brother passed away, an already hard day for my family. My mom wakes up alone in the hospital and is made aware that she has cancer.

Wednesday April 8th: I had 4 classes today but my head was too cloudy to focus on school. I layed in bed and watched This Is Us all day.

Thursday April 9th: I ran errands since my mom is too weak to and my dad is so busy being her nurse. I decided it is no longer safe for my dad to be out running errands since he is by my moms side 24/7. We cannot risk her getting sick with COVID-19 right now. Everyone at the grocery store was wearing gloves and a mask. Sanitizing their cart before they touched it. And of course, staying 6 feet apart.

Friday April 10th: My boyfriend and I’s anniversary which we had planned to spend together and now, cannot. No visitors are allowed given my mom’s extreme condition.

Saturday April 11th: Spent all day cleaning, cooking, taking care of my dogs and little brother while trying to catch up on school work and study for my graduate school entrance exam. One of my friend’s dad passed away from COVID-19.

Sunday April 12th: Easter which usually entails 60 relatives running around my house, eating good food, laughing, drinking and having fun. Instead this year, my dad and brother watched superbowl reruns while I took care of my mom all day.

We can look at all the negative ways in which “no one gave a shit this week.” The hospital “didn’t give a shit” my mom had to be diagnosed with cancer alone. Cancer “didn’t give a shit” to hit hard on a different day that wasn’t already hard for my family. John Cabot University “didn’t give a shit” to cancel class on a day where I didn’t feel like attending. My point is, regardless of the week I had, it happened and life went on.

I didn’t write this piece to sound pathetic and be so negative though. That is in fact completely opposite of how I viewed this week. In a vulnerable time where one needs love and support from family and friends, “no one gave a shit” about not being able to come visit my family and I. “No one gave a shit” about all the social restrictions put in place. My family and friends have completely showered us in love and support at a distance this week. Every day a delivery of either flowers, food, cards, starbucks, bagels, something, is left on my doorstep. My phone is constantly ringing with texts, calls and Facetimes of people reaching out to check on how I am doing. Surprise visitors appear at my back door.

My anniversary plans resulted in eating dinner at the same time over facetime and calling it a dinner date. My family and friends did not let Coronavirus stop them from showing love and support during these trying times. They have found adaptive ways. Regardless of any hardship Corona is bringing us, we can still find ways to stay connected and be there for one another. We can spend our whole lives whining about how life isn’t fair or we can work our way around it. That is what my dad taught me when he started saying, “Welcome to the world of no one gives a shit” and that is what I saw this week from my family and friends. So I encourage everyone this week to stop giving a shit. Don’t let Coronavirus, or anything get in your way. Find ways to adapt so we can keep showing love and support to each other and achieve what we want out of life, regardless of the circumstances.

One thing is fairly clear, though. With the socialist illusion of Corbyn and Sanders gone (as we predicted in Theory of the Precariat), what’s left for the left is mutualism, syndicalism and, especially, dual power. The environment is recovering, now it’s time to recover collective agency and seize power.

One thing is fairly clear, though. With the socialist illusion of Corbyn and Sanders gone (as we predicted in Theory of the Precariat), what’s left for the left is mutualism, syndicalism and, especially, dual power. The environment is recovering, now it’s time to recover collective agency and seize power.